12 Mar 2018

Ian Wright investigates the causes of bacterial infections in felines, discussing various means of limiting the zoonotic risk.

Figure 1. A cat flea.

Bartonella species infections are common in pet cats and thought to be transmitted primarily by fleas. While the health implications for chronically infected cats are still uncertain, the zoonotic impact on human populations exposed to infection via flea infestations may be considerable.

The main route of zoonotic infections was traditionally thought to be via cat scratches, and although human infection can, and does, occur this way, exposure to flea dirt is likely to play a more important role. This is especially true among veterinary professionals and those living with flea household infestations.

This article discusses the treatment and management of feline bartonellosis, and what measures can be taken to limit zoonotic risk.

Bartonellosis is a disease caused by Bartonella species infection and is a zoonosis.

Five Bartonella species are consistently isolated from cats (Bartonella henselae, Bartonella clarridgeiae, Bartonella bovis, Bartonella koehlerae and Bartonella quintana) and three of these (B koehlerae, B henselae and B clarridgeiae) are considered zoonotic. B henselae is the most prevalent, but B clarridgeiae also accounts for a significant number (approximately 10% of feline Bartonella infections).

The prevalence of antibodies to Bartonella in cats has been found to vary widely across Europe, from 0% to as high as 71% in a study of 168 cats in Spain (Solano-Gallego, 2006). The prevalence of B henselae infection in UK cats is high, with a prevalence of 40.6% recorded in domestic cats (Barnes et al, 2000) and 15.3% in Scotland (Bennett et al, 2011). This is of concern, given that domestic cats bring the bacteria into close proximity with people.

Although transmission occurs through abrasions from cats (“cat scratch disease”), flea dirt has been demonstrated to be a significant route of transmission coming into contact with compromised epidermis. Cats predominantly become infected through contact with infected fleas and flea dirt, although ticks may also play a role in transmission.

In the UK, Bartonella species, including B henselae, were detected in 1.3% of the tick samples removed from cats (Duplan, 2018, submitted) and transstadial B henselae has been demonstrated in Ixodes ricinus ticks (Cotté et al, 2008). B henselae transmission has been shown to not occur when infected cats lived together with uninfected cats in a flea-free environment. This suggests cat scratches, close contact, and sharing of food and water bowls are not significant routes of transmission between cats, and emphasises the importance of vectors in transmission.

Zoonotic infection most commonly presents as a self-limiting regional lymphadenopathy developing after a primary papular lesion lasting from a few weeks up to several months (Boulouis et al, 2005). In a minority of cases, this can progress to abscessation of the lymph node, and systemic clinical signs – such as chronic fatigue, headaches, blurred vision and ataxia – are occasionally reported. An increasing number of more serious atypical clinical presentations are being recognised in association with infection, including uveitis and endocarditis (Florin et al, 2008; Tsuneoka et al, 2010).

Bacillary angiomatosis is one of the most common clinical presentations in immunocompromised individuals and may be fatal if untreated (Lange et al, 2009). Veterinary professionals have been identified as high risk groups for infection, as contact with flea dirt is frequent and constant hand washing can lead to a compromised epidermis.

It is difficult to establish what disease syndromes and clinical signs infection may be associated with in cats, as prevalence of infection is high, many positive cats are coinfected with other parasites and high numbers of cats exposed to infection remain subclinical (Bradbury and Lappin, 2009). Associations with a variety of clinical signs have been suggested, including gingivitis, pyrexia of unknown origin, cystitis, uveitis and renal disease.

Isolation of Bartonella species by blood culture is the gold standard diagnosis, but its usefulness in clinical cases is limited by the high prevalence of infection in healthy cats, and that sensitivity can be adversely affected by previous use of antibiotics and the species of Bartonella involved. Sensitivity can be improved by freezing the sample prior to testing and avoiding ethylenediamine-tetra-acetic acid blood tubes.

PCR is widely available from external labs and blood, aqueous humour, cerebrospinal fluid and tissues may all be tested, with the highest sensitivity being yielded from testing a variety of fluids and sites. The high number of subclinical carriers still raises problems in interpreting positive PCR results, however, and other possible causes of presenting clinical signs should be investigated. Serology is available (immunofluorescent antibody test or ELISA), but is of limited value in assessing active infection due to the long persistence of serum IGg in cats.

Diagnosis of clinical infection in cats is, therefore, one of exclusion of other causes in the presence of active infection, and response to treatment with antibiotics. Blood testing for Bartonella species is required for cats being considered as blood donors due to the risk of transmission and subsequent potential zoonotic risk. Cats owned or in regular contact with immune-compromised individuals, or in homes where human bartonellosis has been diagnosed, should also be tested.

Although clinical cases are responsive to antibiotics, they are not guaranteed to eliminate infection, even if long courses are used. Treatment is, therefore, only recommended in cats positive for active infection and with relevant clinical signs, or those positive cats in regular contact with immune-suppressed human individuals that may be at risk of life-threatening disease. No regime of antibiotic treatment has been proven to consistently eliminate infection and even cats that test negative post-treatment often suffer from recurrent bacteraemia.

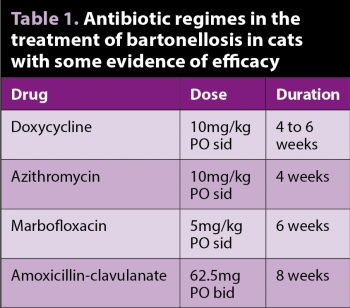

Table 1 summarises the antibiotics used to successfully treat bartonellosis in cats. Doxycycline is a good initial antibiotic choice, but care must be taken to minimise the risk of oesophageal stricture formation – either by using an oral solution or by administering tablets with food or water. The optimum duration of treatment is not known, but should continue for at least four weeks. Azithromycin is used for the treatment of human infections and is sometimes used in cats, but data from controlled studies are lacking.

Treating healthy cats for Bartonella infection is contraindicated, as elimination of infection is far from guaranteed and prolonged treatment with antibiotics may lead to resistant strains of Bartonella. If treating cats, owners should be prepared for the long courses of antibiotics required, with no guarantee of treatment efficacy and the ongoing likelihood of reinfection.

No effective vaccine exists for Bartonella species in cats and antibiotics are not guaranteed to eliminate infection. Even if they are successful, reinfection in the presence of existing flea populations is almost guaranteed.

Treatment of positive cats in the homes of immune-compromised individuals is crucial to prevent immediate exposure, but long-term prevention of Bartonella infections in cats and limiting zoonotic exposure is completely reliant on preventing exposure to fleas and flea dirt. Routine flea treatment with an effective adulticide of all pets susceptible to fleas is, therefore, essential to prevent transmission between cats, reinfection of individuals and to limit zoonotic exposure.

The most common fleas on UK pets are cat fleas (Figure 1) and, therefore, all cats, dogs, rabbits and ferrets in households should be treated with an appropriate flea adulticide at a frequency that will prevent flea egg laying. This will prevent establishment of flea infestations, and flea dirt building up on the coats of pets and in the home. Regular checking for fleas by owners is not an effective alternative strategy as, by the time they are found, infestation will have already established and flea dirt will be present in the home.

All cat owners should take sensible precautions to limit exposure to infection, in addition to adequate flea control, including avoiding interactions with cats likely to result in scratches or bites, supervising children’s interactions with cats, thoroughly washing bites or scratch wounds from cats as soon as they occur, and ensuring new pets are in good health and flea-free on entry to the home.

It is unknown if ticks play a significant role in the transmission of Bartonella, but the use of an effective tick treatment, and regular checking for and removal of ticks (Figure 2), is a sensible precaution in cats with a history of tick exposure or that frequently go outside. No evidence exists declawing cats decreases the probability of zoonotic transmission.

Vet professionals are at particular risk of infection as they will frequently come into contact with flea-infested cats, and flea combing for diagnostic purposes may dislodge substantial volumes of flea dirt and adult fleas (Figure 3). Special precautions are required in the workplace. These include:

Veterinary professionals should be aware of the possibility of infection in the workplace and seek medical advice if they develop relevant clinical signs, particularly after a history of cat bites, scratches or ungloved flea dirt exposure.

Diagnosing infection can require multiple tests and when cats are found positive it does not mean Bartonella species are the cause of presenting clinical signs. Treatment, therefore, should only be initiated where infection is present and other causes of clinical signs have been eliminated, or where immune-compromised human individuals are at risk of exposure.

The zoonotic aspects of Bartonella infection in cats is of greatest concern. It is likely underdiagnosed, with many people being exposed through cat ownership and having uncontrolled flea infestations in their homes.

Prevention of exposure is very achievable, however, and owners should be made aware of the risks without causing undue panic. The mainstay of preventing zoonotic infection is flea control, and this is vital to prevent exposure to Bartonella and other pathogens, while reducing flea-allergic dermatitis, human irritation and strengthening the wonderful bond between cats and their owners. With sensible precautions, this bond can be enjoyed while keeping the zoonotic risk of bartonellosis to a minimum.