2 Apr 2018

Sarah Caney outlines the importance of reducing stress in feline patients and offers tips to help veterinary teams have “cattitude”.

Figure 1. Cats prefer to be on raised surfaces, such as a bench or “cat tree”. The carrier can be covered with a blanket to further reduce stress.

Despite cats’ ability to lower our blood pressure and stress levels, all clinicians will be aware of the susceptibility of feline patients to stress.

A visit to the clinic is highly stressful to feline patients for numerous reasons. Simply getting a cat into a carrier for travel to the clinic is often difficult enough, but many cats dislike car journeys, and may vocalise, urinate, defecate and vomit during even a short journey.

When at the clinic, the sight and smell of unfamiliar people and animals adds to the tension – to the point they may be highly stressed when they finally come into the consulting room. Consequences of stress include altered behaviour, and clinical and laboratory findings, which may make reaching a correct diagnosis more difficult. Stress also reduces recovery from illness, thereby affecting the prognosis.

Relaxed cats are typically easier to handle, so less challenging for clinicians. Carers are often aware of stress in their cats and respond positively to a cat-friendly vet visit. Being cat friendly is, therefore, vital for all clinics.

The term “cat friendly” defines measures that minimise stress to feline patients and improve the quality of care provided.

This can be achieved through improved education and support of the veterinary clinic team, in addition to other practical considerations relating, for example, to building design and layout.

To be cat friendly, clinic teams must understand normal cat behaviour and what stresses cats. A cat-friendly clinic takes steps to reduce and prevent stress in visiting felines. International Cat Care (ICC) has done much to highlight the importance of being cat friendly; this article is merely an introduction to this topic. For more information, the author encourages readers to visit the website for Cat Friendly Clinic – an initiative set up by the International Society of Feline Medicine, the veterinary division of ICC, where resources can be accessed and clinics can be registered for accredited Cat Friendly Clinic status.

An accredited Cat Friendly Clinic has reached a higher standard of cat care, in that staff:

Achieving Cat Friendly Clinic accreditation involves all staff – from receptionists, nurses and technicians, through to vets. Each accredited clinic also has at least one “cat advocate” – someone who ensures the cat-friendly standards are adhered to, and would be happy to talk to clients and colleagues.

Stress can have behavioural, neural, hormonal and immunological consequences. These include activation of two stress pathways – the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, resulting in increased levels of glucocorticoids; and the sympathoadrenal response, resulting in increased levels of catecholamines.

Stress associated with a veterinary examination can have a marked impact on patient assessment. Handling, for example, may be more challenging in an unhappy cat, while many clinical procedures – such as abdominal palpation, oral examination, thyroid palpation and mobility assessment – are more difficult in a tense or stressed cat, meaning a full clinical assessment may not be possible.

Clinical parameters – such as heart rate, respiratory rate, body temperature and systemic blood pressure readings – can all be increased by stress. In one study, the white coat effect (the impact of stress on increasing systemic blood pressure) was as much as 75mmHg in healthy cats (Belew et al, 1999).

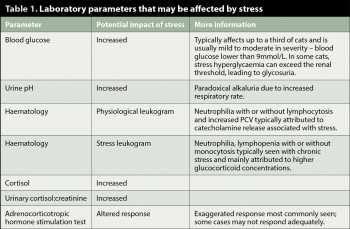

Laboratory parameters that can be affected by stress are summarised in Table 1. Clinical and/or laboratory consequences of stress may prevent an accurate diagnosis from being made or result in an incorrect diagnosis – for example, a stress-associated increase in blood pressure being attributed to systemic hypertension.

Elderly cats – particularly those suffering from cognitive dysfunction, chronic pain, or hearing or visual deficits – often find a veterinary visit highly stressful. Stress is not always manifested in an obvious way, but when apparent to carers, this can reduce the likelihood of them returning for repeat consultations – especially if these are deemed non-essential by them. For example, in one owner survey, 27% of cat owners stated stress to the cat during a visit to the vet was a very important factor when deciding whether to vaccinate (Habacher et al, 2010).

In contrast, an apparently stress-free consultation is appreciated by carers, who are more likely to follow recommendations given, and return for future advice and care.

Chronic stress can impair the ability to metabolise medications and contribute to anorexia in hospitalised cats, thereby prolonging recovery times and worsening the prognosis.

A calm, happy cat will be easier to examine, and provide more accurate clinical and laboratory data – meaning a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment can be provided quicker.

The author has provided tips she has developed through her career, alongside advice freely available on the ICC’s website.

A stress-free veterinary experience for owners and cats starts before they enter the front door of the practice. Advising owners on the most appropriate ways to bring the cat in, and helping the cat remain calm and relaxed, has a positive effect on both cat and owner.

Top-opening carriers – or those easily dismantled – are preferable to ones with a small “front” door, since it will be easier getting the cat in and out. Covering the carrier with a towel can be helpful, and spraying synthetic feline facial pheromone into the basket and covering with a blanket half an hour before it is introduced helps create a reassuring environment.

Once at the clinic, a cat-only waiting room is an advantage, where possible, so cats are not able to see, hear or smell canine patients in the clinic.

The waiting room should be as quiet and calm as possible, with minimum human traffic. Clients should be encouraged to place cat carriers on raised surfaces – such as “cat trees” (Figure 1) or benches – as cats feel more secure on elevated surfaces.

If the waiting room is shared with dogs, pheromone diffusers can help reduce stress levels in canine and feline patients, thereby helping create a calm environment.

Other shared waiting room solutions include:

Cats are very sensitive to smell, so avoid strong air fresheners. After disinfection, rooms should be well ventilated, and pheromone diffusers should be placed in all areas cats visit in the clinic.

All staff interacting with clients benefit from education and training with respect to care of cats. Owners readily detect antipathy or indifference to cats, which may put them off using the clinic again.

A cat-friendly attitude – which ICC has termed “cattitude” – is essential in conveying a strong feline-friendly message. Staff who understand, and welcome, cats and their owners are vital.

Adopting a “less is more” approach to restraint will help prevent cats resorting to aggression. Cats generally respond well to minimal restraint in a calm, quiet environment with a “no rush” approach. If possible, one consulting room should be reserved for examination and handling of cats.

Be prepared to examine cats where they are most comfortable – whether in the carrier with the lid removed (Figure 2), or on a windowsill or the floor. Non-slip surfaces – such as a bath mats with rubberised backing – can provide a comfortable surface for examination.

If a cat shows signs of aggression, it is important to remember this is because it is afraid and distressed. Aggression may be seen when handling or restraining some cats with chronic pain – for example, due to OA.

Further tips include:

Cat-friendly equipment includes paediatric scales in the consultation room, facilities for blood pressure assessment, handheld glucometers for blood glucose determination using a small volume of blood, otoscopes with small cones, small tipped thermometers, an ophthalmoscope and hand lens for ocular examination, and quiet clippers.

Facilities to support patient warming under anaesthesia are helpful. As a minimum, this includes heated pads, “hot hands” (latex gloves filled with warm water), and covering the patient with bubble wrap and towels. Forced-air patient warming systems are also effective in helping small anaesthetised patients maintain their body temperature.

A separate cat ward in a quiet location is ideal, if possible. If the ward is shared with dogs (or very close and not sound insulated), using a dog-appeasing pheromone to reduce canine reactivity can have a secondary beneficial effect on feline patients.

If possible, admit canine surgical patients first so cats are only admitted to the ward once all dogs have received their premedication.

It is helpful to have as much information as possible about the cat’s normal home routine, diet and preferred litter substrate before it is admitted.

If an owner wants to leave something that smells of home – such as the cat’s normal bed or an item of the carer’s clothing – be willing to accept.

Cat owners expect and appreciate a high level of service. Clinics able to demonstrate their friendliness through Cat Friendly Clinic accreditation will be at an advantage, and cats, carers and clinicians will all benefit.