2 Jun 2021

Sarah Caney BVSc, PhD, DSAM(Feline), MRCVS discusses the importance of regular tests in feline patients and offers tips on how to carry this out while social distancing.

Figure 1. Use of an oscillometric monitor.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced access to veterinary care across the UK due to social distancing and lockdown measures aimed at reducing the transmission of the causal virus, SARS-CoV-2.

Procedures where typically two people are involved, such as blood pressure assessment, may have been impacted within clinics due to social distancing concerns, and screening of apparently healthy animals has largely not been possible due to COVID restrictions.

This article reviews why blood pressure assessment is so important, which patients should be prioritised for assessment and the author’s tips for how to do this in a “COVID-friendly” way.

Systemic hypertension (high blood pressure [BP]) is recognised with an increasing frequency in vet clinics dealing with cats.

While it is idiopathic in up to 20% of cases, in most cases it occurs in association with certain medical conditions, such as chronic kidney disease, hyperthyroidism and primary hyperaldosteronism (also known as Conn’s disease).

A recent study reported the incidence risk of hypertension as 11% of cats aged 9 to 13.5 years, 30% of cats aged 13.5 to 18 years and 36% of cats aged 18 to 22.5 years – clearly demonstrating that increasing age increases the risk of hypertension (Conroy et al, 2018).

Hypertension is often referred to as a silent killer since clinical signs may not be apparent until the disease is very advanced.

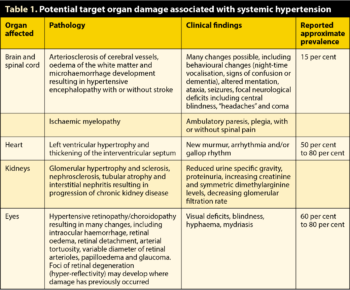

Four “target organs” exist – body systems that are especially vulnerable to the damaging consequences of high BP – these are the kidneys, heart, eyes and CNS (Table 1).

Patients suffering from systemic hypertension may present with clinical signs associated with target organ damage (TOD) and/or clinical signs associated with any underlying systemic disease, or, unfortunately – especially in earlier stages – with no clinical signs at all.

BP assessment is prioritised in all cats presenting with evidence of TOD. In addition, the author recommends screening for systemic hypertension in cats with diseases with a known association – for example, three to six‑monthly BP checks are sensible in all cats with chronic kidney disease.

Preanaesthetic and wellness BP checks are recommended, where possible, in older cats (Panel 1).

Diagnosis: cats showing signs of target organ damage (TOD), such as:

Screening: cats that do not appear to have TOD:

International Cat Care guidelines recommend that annual BP assessment should be included as routine in all cats aged seven years and older, where at all possible.

COVID-19 restrictions may, at times, preclude screening of apparently healthy cats.

Indirect methods of BP measurement are recommended for conscious cats, but unfortunately no methodology is perfect. The author currently finds the Doppler methodology most reliable for BP assessment in conscious cats. If using an oscillometric monitor, a high-definition monitor is preferred (Martel et al, 2013).

Typically, BP assessment involves two handlers – one gently restraining the cat while the other collects measurements. However, social distancing is important in reducing the transmission of SARS-CoV-2; therefore, alternatives should be considered. These include the possibility of collecting BP readings “single-handed”.

The easiest methodology for solo BP assessment is to use an oscillometric monitor where a hands-free approach can be straightforward (Figure 1).

If using the Doppler methodology, it can be helpful to have the cat sitting in the lower half of its carrier as a mild form of “restraint” (Figure 2) with optional treats along the edge of the carrier as a distraction.

However, single-handed BP measurements can take some time to obtain; this needs to be factored into decision-making.

For cats where two people are required to measure BP, options for increasing the distance between colleagues include consideration of using an alternative site, such as the tail, while the assistant restrains/distracts the cat’s head.

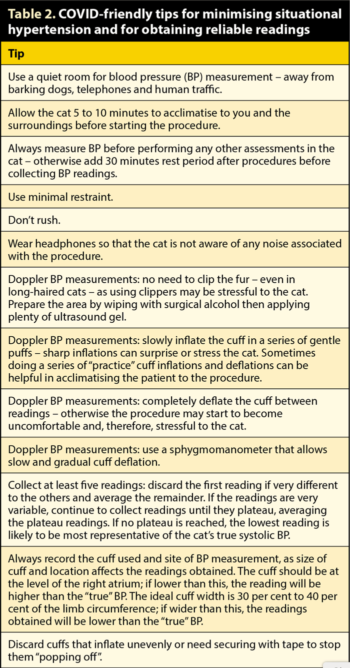

Stress can increase BP readings – so-called “situational hypertension” – so BP assessments should be done in as calm and cat-friendly a manner as possible to reduce the risk of stress complicating interpretation of blood pressure readings.

Anecdotally, many clinicians have been reporting some benefits of “COVID consults” in reducing stress in feline patients.

Firstly, waiting rooms are typically not being used – cats are entering the clinic via a car park handover and proceeding straight to a consult room.

Secondly, the clinic itself is often much quieter due to fewer people and animals simultaneously present inside the building.

COVID-19 may, therefore, have had some positive impacts in reducing stress and, hence, reducing situational hypertension in cats.

Pre-visit gabapentin is useful – especially in anxious cats – in providing mild sedation, which can reduce restraint required and increase the likelihood of successful solo BP assessments while not affecting blood pressure readings. A dose of 20mg/kg bodyweight given in a small amount of food two or three hours prior to the appointment typically results in a slightly sedate cat with a duration of about four to six hours (van Haaften et al, 2017). It is important to note that gabapentin does not have veterinary authorisation for this use in cats.

Butorphanol 0.4mg/kg SC or IM injection can also be effective as an in-clinic mild sedative for cats that does not impact on BP readings.

Additional tips for minimising situational hypertension and obtaining reliable BP readings are in Table 2.

Assessment of patients for evidence of TOD (Table 1) can be extremely helpful in confirming systemic hypertension.

If a single high BP reading is obtained, but no evidence of TOD exists, BP measurements should be repeated again on another day to confirm persistence of high readings before treatment is considered. Conversely, if clear evidence exists of TOD and a single high reading, this confirms the diagnosis of systemic hypertension and treatment can be started.

Looking for evidence of ocular TOD is especially important; it has been estimated that 60% to 80% of hypertensive cats have ocular TOD.

Fundus examination using distant indirect ophthalmoscopy, performed at arm’s-length distance from the cat, is a quick and easy way of assessing the eyes that can be done with colleagues 1m to 2m apart, and in some cases without assistance from a colleague. This procedure is performed in a completely dark room, and the only equipment needed is a 20-dioptre to 30-dioptre handheld lens and a dimmable light source.

Inexpensive acrylic lenses are available, typically for less than £50, and a direct ophthalmoscope set to a small circle can be used as a light source.

If a dark room is not available, it may be necessary to dilate the pupils using tropicamide drops. These take up to 15 minutes to exert their effect and will typically last for several hours.

To perform distant indirect ophthalmoscopy, the examiner stands at arm’s length from the cat and starts by directing the light source towards the cat’s eye, adjusting the angle of the light beam until a bright tapetal reflection is seen. Sometimes this is possible without the cat being restrained; in other situations it can be helpful to have a colleague present to gently restrain the cat and raise its chin so it is not looking down at the floor.

Once the bright tapetal reflection is seen, the hand lens is inserted just in front of the eye, perpendicular to the beam of light (Figure 3). The “belly” (bulging side) of the lens should be facing the examiner (“belly to belly”). An inverted image of the fundus is seen and the lens magnification typically ensures that much of the fundus is visible in one view. The lowest light intensity resulting in a good image should be used; cats typically dislike having very bright lights shone into their eyes.

This technique is excellent for visualisation of large portions of the fundus quickly in the clinic.

If lesions are evident then direct ophthalmoscopy can be helpful in examining these at a higher magnification.

A number of ocular pathological abnormalities are possible with systemic hypertension (Table 1). Video guides on indirect ophthalmoscopy and annotated images of a variety of abnormalities are available on the author’s website (Caney, 2019a; 2019b) and elsewhere.

In situations where time or other constraints prevent BP measurement, distant indirect ophthalmoscopy can usually be included.

Where fundus lesions consistent with systemic hypertension are seen, BP measurement should be prioritised as a matter of urgency.

Systemic hypertension is defined as persistent, pathological increase in systolic BP (SBP; 160mmHg or higher). Several (preferably a minimum of five) SBP readings should be collected and an average calculated.

Since situational hypertension can result in SBP readings transiently 160mmHg or higher, systemic hypertension is only confirmed in cats with an average SBP of 160mmHg or higher if:

Where diagnosed, systemic hypertension is typically very straightforward to manage with antihypertensive therapies such as amlodipine and/or telmisartan.

Further information on management of systemic hypertension is reviewed extensively elsewhere (Taylor et al, 2017; Acierno et al, 2018).