13 Apr 2018

David Sargan provides a detailed picture of what is known about the health and welfare of these dogs – looking at the general health of breeds, whether better individuals exist and how these can be recognised.

Image © ivanovgood / Pixabay

It is unlikely anyone reading this article does not know about one of the most inflammatory controversies in small animal practice.

Is the breeding of brachycephalic animals – particularly dogs – so cruel it should be made illegal? Or, are the few minor problems outweighed by the good features of these breeds and enough to prevent dogs living happy lives?

The debate is highly emotive, with both sides of the argument finding it difficult to attribute any but the worst of motives to the other.

As well as discussing what is known about the health and welfare of brachycephalic dogs, the author will look at why these breeds are considered valuable by so many – asking why they should be saved and what can be practically done to reduce their associated health burden.

The tendency of humans to select for short skulls in domesticated animals can be seen in many species – including pigeons, goats, pigs and rabbits (Figure 1). However, it is most familiar in cats – such as the Persian – and particularly dogs. These skull shapes are often associated with pet animals, as opposed to commercially important or working animals.

For some individuals in many of these breeds, well-known health difficulties exist that have been best characterised in dogs. These include noisy and laboured breathing – characterised by both stertors and, in some cases, stridors – exercise intolerance, heat intolerance, sleep apnoea, regurgitation and, in the worst cases, cyanosis, collapse and death1–4.

In addition, the reshaping and repositioning of eye sockets is directly causal of exophthalmos and problems associated with increased corneal damage, while the reduced jaw lengths lead to overcrowding of teeth, malocclusion and associated bite problems.

The large head can cause problems in birthing in several dog breeds, while excessive skin causes abundant wrinkling with associated dermatological problems.

The exaggerated conformations of the breeds may induce other skeletal defects – including vertebral, limb and tail malformations – though it is unclear whether these are directly selected for in developing the brachycephalic skull.

Many people find animals with shortened skulls cuter than breeds with more wild-type skulls – a tendency as evident in the shape of teddy bears, or public feelings about pandas compared to other ursids, as it is in dog breeds.

This is almost certainly because humans are programmed to respond strongly to infant faces, which are highly brachycephalic (Figure 2). Oxytocin release occurs in dogs and humans during relaxed and pleasurable social interactions, and interactions with babies are powerful cues for oxytocin and dopamine release in humans.

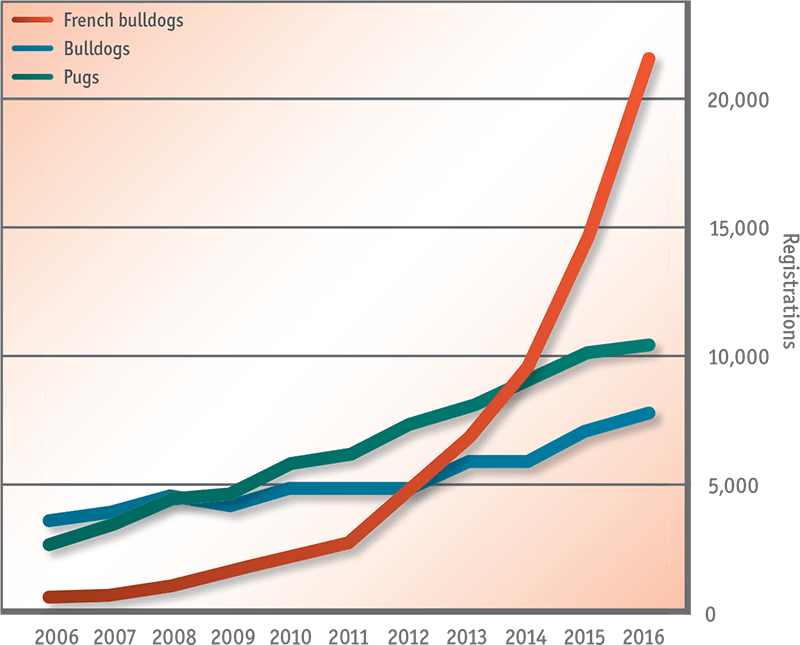

The three most popular brachycephalic breeds – French bulldog, pug and bulldog – have boomed in popularity in the past 20 years (Figure 3), to the point where the French bulldog is likely to be the second most popular breed in registrations with The Kennel Club (KC), with the other two breeds in the top 10. Together, these three breeds accounted for more than 20% of all registrations with The KC in the first six months of last year.

Increases in popularity of extreme brachycephalic breeds of other species has been more limited. Registrations by The Governing Council of the Cat Fancy of Persian and exotic shorthair breeds – the most common extreme brachycephalics – have declined in the past eight years, although moderate brachycephalic breeds show relative increases.

However, in dogs and cats, skull shapes in brachycephalic breeds appear to have become more extreme in recent decades.

Causes of the boom in numbers are somewhat speculative, but in addition to cuteness, may include encouragement from various sources.

Although not having been surveyed systematically, the number of firms using brachycephalic dogs as marketing tools is probably greater than the number using all other breeds. A huge range of celebrity role models – including sportsmen, actors and actresses, and supermodels – own these dogs, while films and TV feature them prominently.

These breeds are claimed as the friendliest dogs by their owners. In interactions with dogs and humans, brachycephalic dogs often accept submissive, appeasing roles, but are also active in play and gaze bonding.

Surveys show most owners do not recognise abnormal breathing, or claim it as “normal for the breed”. Vets also disagree in their interpretation of breathing noises by these dogs.

It has been very important to develop objective means to measure breathing. This has been done using computer analyses of whole-body barometric plethysmography on unsedated dogs, and developing treatments of these data that correlate closely with exercise performance7,8. This allows exercise tolerance tests – backed by auscultation – to be applied to individual dogs, to reach consistent conclusions about the degree of brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome (BOAS) in individual dogs.

It is often suggested in social media these dogs need very little exercise, and smaller breeds are suitable to be carried and live indoors. Of course, dogs of all breeds need daily exercise to remain healthy.

As aforementioned, dogs that often appear to grin when panting, or make appeasement gestures, are thought of as smiling or laughing, when, actually, these are connected with distress and appeasement.

YouTube and other social media love videos of dogs trying to sleep while sitting, or of dogs falling asleep briefly and frequently during the day. This is interpreted as hilarious laziness, but is a profound welfare problem. An example:

The welfare burden of a given disease is usually thought of as a combination of four factors:

The number of animals is large and increasing. None of the three numbers defining the individual burden is known accurately, but some rather soft numbers are known.

The prevalence of upper respiratory disease, as measured in primary practice9 (Vet Compass project), relies on recognition and reporting by owners, but may be about 20% in extreme brachycephalic breeds. Meanwhile, objective measurement of BOAS in show populations by the Cambridge BOAS Research Group gave considerably higher numbers – 40% to 60% of dogs older than one year.

However, for most of these dogs, although BOAS is clinically significant – severe enough to interfere with fairly intense exercise and potentially with cooling in warm weather – it was not causing significant and immediate welfare problems to the dog. Only for one in eight dogs tested was immediate veterinary consultation with a view to treatment suggested, based on the dog having severe BOAS. Prevalence of severe BOAS increases somewhat with age, but remains at about 20% in dogs older than three years, in agreement with the reporting by primary practices.

The prevalence of the other brachycephalic syndromic conditions, including eye and skin problems, has been measured in relatively small surveys of the pedigree population by owner responses to questionnaires. In general, each problem is reported in between 5% and 20% of individuals of the extreme breeds. The proportion of dogs suffering more than one condition related to brachycephaly is unknown.

An intelligent guess would be syndromic morbidities associated with brachycephaly cause moderate or severe welfare conditions to between 20% and 33% of extreme brachycephalic dogs, and last for a considerable period if left untreated – often more than half of the dog’s lifetime.

BOAS can be alleviated by surgery but although this reduces signs somewhat, functionally relevant levels of disorder remain for about half of dogs10. Surgery is complex and expensive, and gradual reversion to a more severe condition occurs for some dogs.

To summarise, a minority – but still a relatively high proportion – of dogs of extreme brachycephalic breeds suffer moderate to severe welfare problems over a long period, associated with their conformation. This welfare burden is very severe for a smaller proportion of each breed.

The rapid increase in numbers in these breeds will inevitably expose more dogs to these problems as they age.

However, they are not all bad.

Despite the problems for many brachycephalic dogs, an ethical balance needs to be considered in deciding how to approach these breeds.

Pets undoubtedly confer benefits to their owners, reflected in both physical and mental health11. These include psychological, social and exercise benefits to the elderly, independent of their health. In particular, brachycephalic dogs are popularly considered as ideal pets for older owners, or those who have less access to space, because they offer companionship and “convenience” to lonely and isolated individuals. The smaller brachycephalic breeds, while needing daily exercise, are capable of less exercise than most dogs, so are, to some degree, more suited to elderly and infirm owners.

Some evidence, based on detailed owner surveys, show brachycephalic dogs are more friendly to humans – owners and strangers – than other dog breeds, enjoy play with both humans and dogs, and are less likely to be aggressive with other dogs12,13. Brachycephalic dog owners usually report particularly strong attachment to their pets.

In owner-dog contacts, this type of attachment is associated with oxytocin release – particularly when contact includes long gazing, which is associated with a strong feeling of well-being. As yet, no well-controlled evidence exists to quantify this as greater for brachycephalic breeds than others, but owners of brachycephalic dogs generally do not want to give them up, even when they have lost animals to brachycephalic syndrome.

It is also probable the owner of a brachycephalic dog benefits from a greater level of human interaction than owners of other breeds, as these dogs are generally seen as non-threatening and provoke conversation when being walked or in other social settings.

Groups such as the Brachycephalic Working Group (BWG), the Campaign for the Responsible Use of Flat-Faced Animals and the BVA are trying to reduce the use of brachycephalic images in advertising and publicity, and publicising adverse health issues, in the hope this will reduce demand.

The BWG is, potentially, a particularly influential body because it includes representatives of the breed clubs, The KC, the veterinary profession, major animal charities and academic researchers. However, it is not yet clear how effective these appeals are on demand or on influencing public behaviour.

The UK breed clubs for the three extreme brachycephalic breeds have introduced health testing for the dogs. This includes exercise testing, eye and mouth health, and some aspects of back and tail health.

The certificates of health issued through these schemes are valued by more informed owners. The experience of the Cambridge BOAS Research Group is these measures seem to be having some effect on prevalence of BOAS in UK show populations. However, penetrance of the pet and non-showing population by these schemes is very small and public knowledge of these problems is limited.

It seems unlikely most prospective owners will go to the expense of putting their dog through these tests and, in any case, full penetrance of several conditions is only present after breeding from the dogs has started – somewhat limiting the consequences of withdrawing affected dogs from the breeding population.

The most rapid solution to eliminate the health problem would be to stop all breeding of brachycephalic dogs, but this gives the problem of identifying breeds – and breed types for non-pedigree animals – to prevent from breeding, as well as legal enforcement.

No absolute limit can be used to say dogs with a certain skull shape will suffer no difficulties, while dogs with a more extreme skull shape will have problems. Indeed, 50% of registered dogs of the most extreme breeds do not have problems in breathing that cause welfare differences, with severe issues present in fewer than 20%. These practicalities may make legislation unlikely, so it is debatable whether good legislation is possible.

A second alternative is to breed healthier dogs. One way to do this rapidly could be by outbreeding to a longer-skulled dog. The Cambridge BOAS Research Group has been unable to replicate in-show population studies suggesting craniofacial ratio has a close association with breathing in all brachycephalic breeds14,15. However, BOAS has not been seen in mesaticephalic dogs.

A second alternative is to breed healthier dogs. One way to do this rapidly could be by outbreeding to a longer-skulled dog. The Cambridge BOAS Research Group has been unable to replicate in-show population studies suggesting craniofacial ratio has a close association with breathing in all brachycephalic breeds14,15. However, BOAS has not been seen in mesaticephalic dogs.

It is likely dogs with nose lengths bringing them into this range will not suffer BOAS, and will have reduced prevalence and severity of other brachycephalic syndrome disorders. Until now, the breed clubs have resisted out-crossing and substantial numbers of owners are likely to continue to do so. It is also probable large numbers of out-crosses would be needed to substantially shift the skull length; each registered breed has little or no variation at the loci that have the largest effects on skull length, with all dogs having the mutant form.

If numbers of these dogs are maintained, spreading a new gene through the population will take a considerable number of generations and a small group of founder crosses could actually lead to further inbreeding. Furthermore, the complexities of skull development and behavioural genetics mean it will be extremely difficult to change skull characteristics by this method while retaining behavioural traits.

Finally, the partial penetrance of the brachycephalic syndrome in a population, despite uniform genetics at major loci controlling skull length, suggests simply breeding away from these loci may not be the most efficient way of achieving a disease-free population.

Another alternative that has more approval from the breed clubs is to use DNA-directed selection within the breeds.

Identification and use in selection of loci, directly associated with disease status, will give better selective responses than using health testing, because the results of the test are not dependent on the environment, diet or exercise regime of the tested dog, and are available before sexual maturity of the dog.

However, the genetics of the disease are complex. Results in Cambridge suggested about 8 to 12 separate genes in each breed have effects on BOAS. It will not be appropriate to remove from the population all dogs with mutant forms at only one of these loci, as this would stop nearly all dogs from breeding, including many that would not be affected by disease and very unlikely to pass it to offspring.

Instead, a usable genetic test will require the development of genomic breeding values, where the change caused by different combinations of disadvantageous alleles is estimated for all combinations of loci, and testing gives a likelihood of a given severity of disease. This will require a large amount of development work, but would allow the removal of severely affected animals from breeding in the most efficient manner.

At this stage, it is important for vets to understand the problems of brachycephaly, be able to inform clients of the health and welfare needs and problems the breeds face, and, if appropriate, be able to suggest other breeds suitable for heir circumstances.