31 Oct 2022

Ron Ofri PhD, DECVO, DVM provides guidelines to distinguish between three clinical entities of this presentation in companion animals.

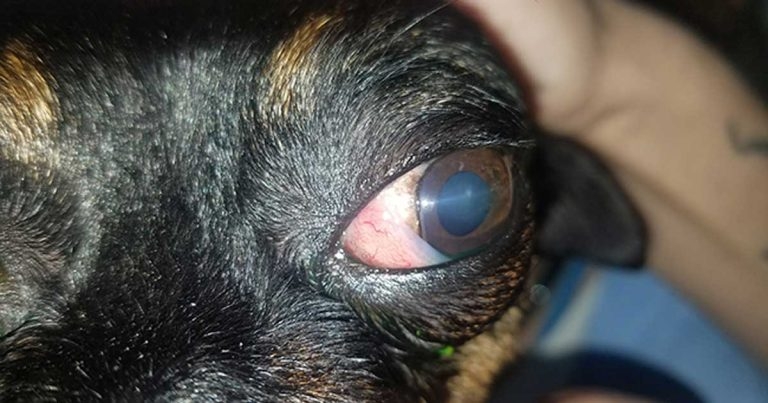

Figure 1. A dog with exophthalmos due to a retrobulbar tumour. Strabismus and protrusion of the third eyelid are also evident.

As a clinician, your patient may be presented for a “bulging” eye. The eyes of the patient are clearly disproportionate, with one eye more prominent than the other.

This presentation may be due to three distinctly different diseases:

The diagnosis of traumatic proptosis is relatively straightforward. Owners will often report a head trauma, or a runaway pet that returned with this presentation.

Clinical examination will reveal that the patient is unable to blink as the eye is now bulging out of the orbit – often to the extent that the eyelids are behind the equator of the globe (Figure 2). Depending on the duration of the proptosis, the cornea may be desiccated or ulcerated.

Additional signs of ocular trauma – including subconjunctival and/or intraocular haemorrhage, severed extraocular muscles, strabismus and lens luxation – are often present. Besides proptosis, the patient may be suffering from injuries to the head and other organs.

Differentiating between exophthalmos and buphthalmos may be more challenging. The ultimate diagnosis should be based on imaging of the retrobulbar space, using ultrasound and/or CT, to detect a space-occupying mass causing exophthalmos (Figure 3); and on tonometry for the diagnosis of glaucoma as a cause of buphthalmos.

However, in addition to these definitive diagnostic tests, a number of clinical signs may help you in deciding whether the patient’s eye is exophthalmic or buphthalmic:

Conduct a retropulsion test by pushing gently on both globes (through the upper eyelids). If a space-occupying, retrobulbar mass is causing exophthalmos, you will feel resistance to the pushing, compared to the unaffected eye. On the other hand, a buphthalmic eye may feel harder than the unaffected eye, but it will readily be pushed into the orbit.

In addition to these signs, exophthalmos and buphthalmos/glaucoma are also characterised by unique signs. Unique signs of glaucoma are discussed in BSAVA Congress Times 2019.

The two leading causes of exophthalmos are a retrobulbar abscess/cellulitis and a retrobulbar tumour. In addition to the previously described signs, and regardless of the nature of the mass, patients will often present with the following:

Unilateral disease. Reports of bilateral, retrobulbar abscess or neoplasia exist; however, these are rare presentations, and the diseases are nearly always unilateral (Figures 1, 4a and 4b).

Once again, an ultimate test exists to differentiate between the two masses. Cytological evaluation of an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration should tell you whether the mass is inflammatory or neoplastic (Figure 5).

A study by Fischer et al (2018) reported that the most common causes of a retrobulbar abscess are foreign body penetration through the oral cavity, as the animal chews sticks or other objects, and dental disease. However, in a majority of cases, the cause was not determined. More than half the patients were Labrador retrievers and spaniels, and aerobic bacteria were isolated from two out of three of the dogs sampled.

In addition to the aforementioned clinical signs that generally characterise exophthalmos, retrobulbar abscess has a few clinical signs that are almost pathognomonic.

The disease is characterised by acute onset and severe pain. The pain is caused when the condyle of the mandible presses on the abscess whenever the animal opens its mouth. This leads to refusal to eat and great resistance to opening the mouth for examination.

It is often necessary to sedate the animal to open its mouth. Once the mouth has been opened, it is often possible to see red swelling, or even an open draining tract, in the oral mucosa, behind the last upper molar tooth.

If no gross lesion is visible in the oral cavity, it is possible to use imaging techniques, such as ultrasound or CT, to image the retrobulbar space. This may also demonstrate foreign bodies, or allow to perform guided fine needle aspirations for cytological diagnosis.

Treatment of a retrobulbar abscess requires general anaesthesia. This is because the patient must be intubated to avoid aspiration of exudate when the abscess is drained.

Make an incision in the mucosa behind the last upper molar tooth (unless an open draining tract is present) and slowly inset a pair of curved haemostats. These are used to blindly explore the orbit and open pockets of exudate.

One must never close the haemostats while in the orbit, as this could lead to crushing of the orbital vessels or optic nerve and blindness. Instead, the haemostats are inserted closed into the tract; they are opened in the orbit, withdrawn while open, closed in the oral cavity and re-inserted into the orbit in the closed position (Figure 6).

If a pocket of exudate is encountered, copious amounts of exudate will flow out. This can be collected for cytology, and culture and sensitivity. In cases of retrobulbar cellulitis, no massive drainage of exudate will be seen. However, the very act of establishing a draining tract is usually sufficient to achieve a cure.

After creating a draining tract, the clinician should gently flush the orbit with saline and antibiotics. The wound is not sutured. Systemic antibiotics are administered for 10 to 14 days, and the animal fed soft food. Hot packs and lubrication of the cornea to prevent desiccation should be considered. However, dramatic and most rewarding, improvement is usually observed within one to two days.

If the animal does not respond to therapy, or in case of recurrence, surgical exploration for a foreign body may be required.

As with any other organ, tumours in the orbit can be primary, or metastasis from nearby or distant regions.

As noted, retrobulbar tumours share a number of signs with retrobulbar abscesses. However, in contrast to retrobulbar abscesses, retrobulbar tumours are usually very slowly progressive and non-painful (at least in the initial stages).

Furthermore, patients with retrobulbar tumours are 10 to 11 years old, on average – significantly older than patients with retrobulbar abscesses.

A retrobulbar tumour can cause deformation of the posterior part of the globe. This deformation can be visualised ophthalmoscopically or using an ultrasound. In addition to exophthalmos, the tumour can also cause deviation of the globe, with the direction of the deviation hinting at the location of the mass, Once again, the diagnosis is based on cytology. However, CT or MRI is required to establish the involvement of the orbital bones, brain and nasal sinuses to determine prognosis and planning of possible surgery.

Solitary tumours discovered in early stages may be removed surgically. In such cases, the best surgical approach is usually oribitotomy, and it may be possible to preserve the globe and vision. Advanced cases may require radical orbitectomy, combined with radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy.

However, most tumours are discovered in advanced stages, and due to their malignant nature they carry a very poor prognosis. One retrospective study reported a mean survival time of one month in cats and 10 months in dogs, with 35 per cent of patients euthanised at the time of diagnosis.