10 Sept 2024

Neil Mottram discusses dogs’ reproductive physiology, some of the potential health detriments of surgery and fresh thinking on alternatives.

Image © Michael / Adobe Stock

Canine castration is one of the most commonly performed procedures in veterinary practice and has been a long established pillar of responsible pet ownership.

The newly published WSAVA global guidelines in reproduction control highlight the latest science-based information on neutering and detail the potential benefits of medical castration. The authors hope this will lead to a tailored recommendation based on the individual animal’s health and client preferences.

In the UK, approximately 70% of dogs are surgically castrated and the procedure is often viewed alongside the likes of vaccination and parasite control: an action to be taken early in an animal’s life to protect its health and that of the population more generally.

While it is true some prostatic and testicular diseases will be diminished or reduced with surgical castration, evidence also shows that surgical castration may contribute to health detriments (such as neoplasia or endocrine diseases), which is currently under intense investigation.

Surgical castration may have far wider-reaching consequences than just controlling the animal’s reproductive status.

To recognise this, an understanding of the normal reproductive physiology of the dog is required.

The two principal functions of the male reproductive system are to produce sperm and the steroid hormone, testosterone.

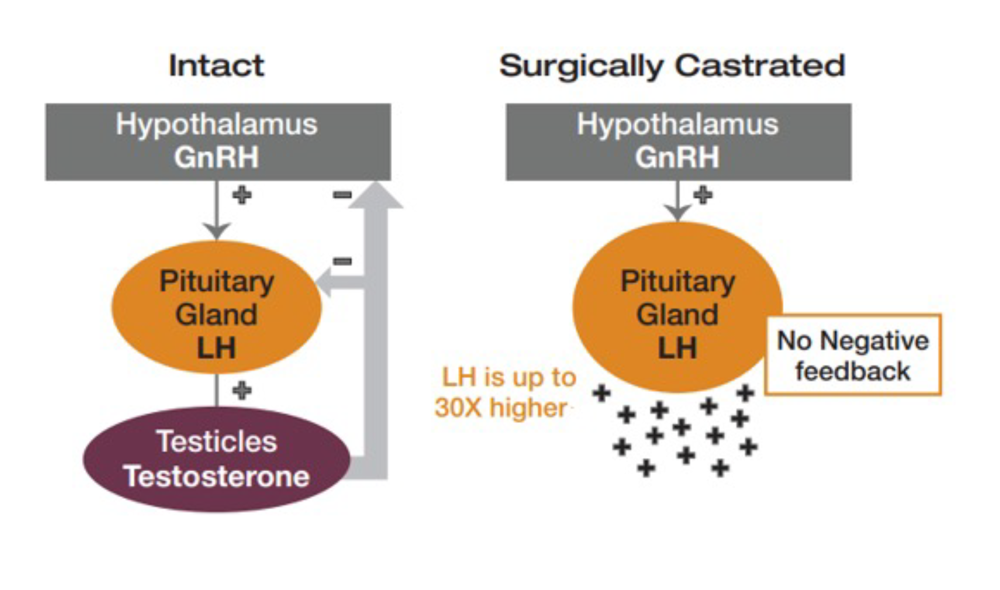

The gonadotrophins, luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), are secreted by the anterior pituitary gland in response to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) production from the hypothalamus, which is released in a pulsatile manner.

In the testes, LH binds to receptors on Leydig cells and stimulates the synthesis and secretion of testosterone. In addition to its systemic effects, testosterone also acts locally in conjunction with FSH to support spermatogenesis through stimulation of the Sertoli cells in the testis.

There is an integrated negative feedback system for the control of hormone secretion; testosterone and its metabolites oestradiol and dihydrotestosterone provide negative feedback at the level of the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. This contributes to the regulation of GnRH release and therefore regulation of the gonadotrophins, LH and FSH.

When surgically castrating male dogs (total gonadectomy), the gonads producing testosterone are removed and, as such, the negative feedback mechanism fails and the normal cascade of hormones produced in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland is disrupted (Figure 1). There is now persistent production of LH.

Figure 1. Graphic showing the negative feedback loop with a pulsatile release of testosterone. This feedback loop fails with the removal of testosterone and leads to supra-physiological concentrations of luteinising hormone.

The WSAVA guidance details the possible health detriments as a consequence of surgical castration and attributes a possible link between some types of neoplasia (including mast cell tumour, osteosarcoma and lymphoma) as well as negative effects on joint health, obesity and some endocrine diseases.

Further research investigating the role of supra-physiological LH is reported by Kutzler at al1, who report the risk for developing several malignancies increases with neutering. In fact, neutered dogs are 1.3 to 2 times more likely to develop osteosarcoma, neutered males are three times as likely to develop lymphoma and neutered females are five times as likely to develop cardiac haemagiosarcoma as un-neutered females.

LH receptors are expressed in these malignant tissues and research in isolated canine lymphoma cells has shown that LH stimulates cell proliferation2. The same can be said for some joint diseases; incidence of hip dysplasia and anterior cruciate ligament tears increases 1.5-2 times in neutered dogs compared to unneutered dogs.

LH receptors are present in these tissues and continuous LHR activation can increase joint laxity mediated by nitric oxide release3. The guidance highlights the need for vets and pet owners to have an awareness that changes to reproductive physiology may have far wider-reaching consequences on the animal, with new evidence in this field continually emerging that may change the risk/benefit assessment of surgical neutering decisions.

“The WSAVA guidance details the possible health detriments as a consequence of surgical castration and attributes a possible link between some types of neoplasia (including mast cell tumour, osteosarcoma and lymphoma) as well as negative effects on joint health, obesity and some endocrine diseases.”

A belief exists that castration could help improve pet behaviour, and although some testosterone behaviours may be improved, many behaviours are multi-factorial. A client questionnaire study highlighted it may have increased the number of dogs being fearful of other dogs, humans or noises4.

The guidance highlights concerns about increasing moves to early neutering, or for neutering to be used as a method of behavioural control, as not all aggressive behaviours are testosterone related, so, using a “castration trial” with long-acting temporary GnRH agonist, such as deslorelin (Suprelorin; Virbac), is recommended by the report before irreversible orchiectomy is performed. While situations exist where a lowered testosterone can be beneficial, with some sexually driven behaviours it is highlighted by the WSAVA that this should not be a blanket treatment – and in fact in some cases it will make things worse.

When it comes to making the decision to neuter their pet, owners need to have an informed discussion with their veterinary practice and be aware of the options available. Many owners may be apprehensive to commit to surgical neutering; this could be from the fear of permanency, behavioural changes or the need for a general anaesthetic5. Many owners also wish to know how neutering may impact their pet, and offering medical alternatives may offer a more attractive temporary solution6.

The new WSAVA guidance prompted a call for a move away from the one-size-fits-all approach and for vets and owners to make individual recommendations for each pet.

The summary of the report can be found at bit.ly/WSAVAneutering