28 Jan 2020

Francesco Cian, DVM, DipECVCP, FRCPath, MRCVS, discusses the case of Nala, a nine-month-old Dobermann referred for a small lesion on her nose in the first of his Diagnostic Dilemmas series.

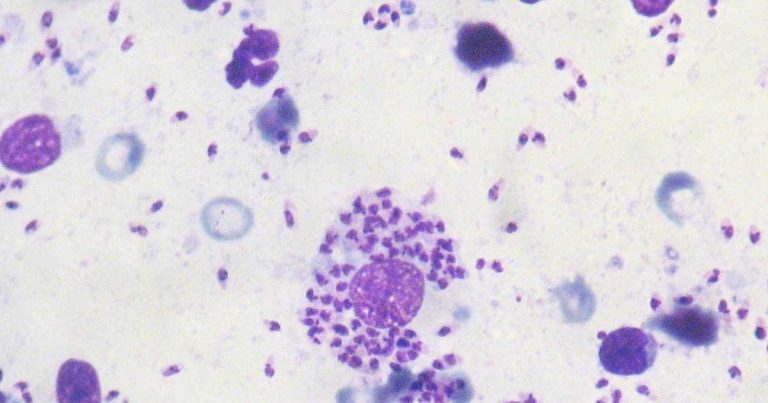

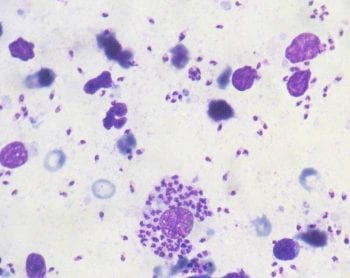

Macroscopic and microscopic appearance of a pink, raised lesion on the left side of the nose in a Dobermann.

Nala is a nine-month-old Dobermann referred to the veterinarian for a small lesion on the left side of the nose.

The lesion was approximately 1cm in diameter, pink in colour, raised, alopecic, soft at touch and with distinct borders.

Its macroscopic appearance and the young age of the dog were considered highly suggestive of cutaneous histiocytoma. This is a benign neoplasm often appearing as a single, red, raised mass on the head of young dogs and often undergoing spontaneous regression within a few months.

The veterinarian performed a fine needle aspirate of the lesion and submitted the slide to an external laboratory for cytological examination.

The aspirate harvested moderate numbers of nucleated cells – likely a mixture of neutrophils, small lymphocytes, macrophages and few bare nuclei.

These appeared as large mononuclear cells with abundant clear, sometimes foamy, cytoplasm containing large numbers of intracellular organisms having a characteristic appearance of Leishmania species, which were also seen in the background (see inset microscopic image).

The intracellular organisms, known as amastigotes, measured approximately 1.5 × 2.5 micron, and had a red nucleus and a characteristic bar-shaped kinetoplast.

The diagnosis was mixed inflammation with Leishmania species microorganisms.

Never deny a cytology sample when in the presence of a solid lesion as its macroscopic appearance and the clinical context may sometimes be misleading, and are often not sufficient to predict its nature and clinical progression.

Leishmaniosis is a vector-borne disease caused by a protozoan parasite that is spread by phlebotomine sandflies. This disease is endemic in several Mediterranean countries and cases in the UK may be observed in dogs with history of travelling in those areas – as happened in this specific case.

The incubation period can vary from three months to several years, as this is dependent on the immune response of the individual animal. Dogs may present with a wide spectrum of clinical signs and clinicopathological abnormalities, ranging in severity from mild and self-limiting to fatal disease (for example, cutaneous lesions, enlarged lymph nodes and chronic kidney disease).

If a dog is examined because of clinical abnormalities compatible with Leishmania species, the veterinarian should sample any accessible lesion to obtain cytologic smears or biopsies.

If Leishmania species amastigotes are identified on cytology, the dog should be considered infected. Conversely, if cytology is negative, but the dog shows specific clinical signs, the presence of infection should be assessed by other tests, since cytology has been reported to have a low sensitivity for the detection of the disease.

These tests include serology by immunofluorescent antibody test, ELISA and/or immunocromatographic test. PCR testing is also available.

Bone marrow, lymph, nodes and spleen are the tissues with the highest potential prevalence for the detection by PCR; whole blood can also be used, but the sensitivity is lower than in the aforementioned tissues.

Aspiration and non-aspiration needle techniques are usually preferred for diagnostic cytopathology and should be performed whenever a solid, raised skin (or SC) lesion is present.

The choice between aspiration and non-aspiration procedures depend on the likeliness of cells to exfoliate, the degree of vascularisation of the lesion and the fragility of cells in the sampled tissue. Solid and poorly vascularised masses can be approached with aspiration technique.

Soft and vascularised lesions and lymph nodes are preferably sampled with the use of a needle only to reduce the chances of cell damage and avoid blood contamination. When in the mass, the needle should always be redirected in multiple directions to obtain a cytology sample that is representative of the entire lesion.

Impression techniques may be used for ulcerated lesions. However, these are often of limited value because they tend to sample only the surface portion of the lesion (for example, inflammatory cells and keratinocytes) and rarely include cells from deeper tissues.