20 Jun 2022

Kate Parkinson BVSc, MRCVS demonstrates a rare occurrence of this condition in a young patient, and how practitioners can successfully treat it.

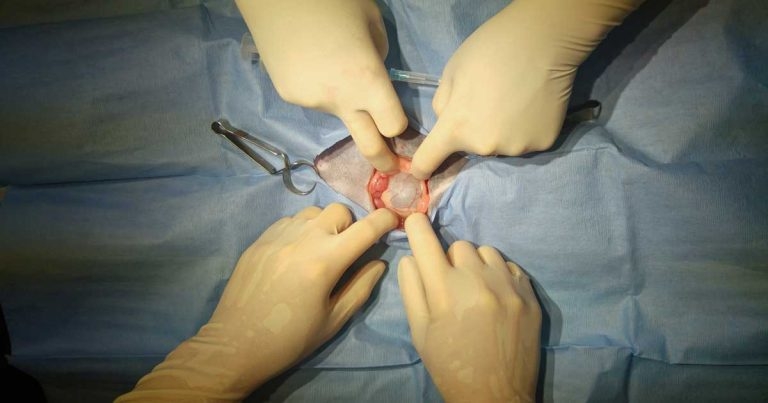

Appearance of the pseudocyst following midline celiotomy.

A 15-week-old female, domestic short-haired kitten is presented with a bloated abdomen four weeks after primary vaccination.

The kitten was smaller than its littermate and was not gaining weight. A fluid-filled viscus was felt during abdominal palpation. A congenital abnormality of the kidney or bladder was suspected, and an abdominal ultrasound scan was recommended.

The kitten presented six days later for its second vaccination. An abdominal mass was easily palpable around the left kidney. The kitten had lost a small amount of weight.

A conscious ultrasound scan revealed a large anechoic cyst with a linear septum surrounding the left kidney. The cyst measured 6.7cm by 4.3cm. The left kidney measured 2.7cm in length with a hyperechoic cortex, but otherwise appeared relatively normal. The right kidney measured 3.4cm in length with a normal appearance.

Blood samples were taken to check renal parameters, which were all within normal limits. A perirenal pseudocyst was suspected and a local referral centre was contacted for case advice before speaking to the owners. Referral clinicians agreed that ultrasound images of the cyst were very similar to a pseudocyst.

Percutaneous drainage of the cyst with ultrasonographic guidance was recommended for fluid culture and cytology. Cystocentesis and full urinalysis was also recommended to investigate renal function. Referral was offered at this point, but declined.

Ultrasound imaging of the abdomen was carried out by a certified ultrasonographer under sedation. The cyst was drained aseptically and 89ml of a serosanguineous fluid was removed with only a small amount remaining.

The cyst wall was smooth and approximately 2mm thick. The left kidney demonstrated reduced medullary architecture. No abnormalities were detected in the right kidney and the ureters appeared normal. Urine was collected via cystocentesis for analysis and culture.

A very small amount of free fluid was noted cranial to the bladder post-drainage. This could have been caused by leakage of fluid during the drainage procedure, although a small amount of free abdominal fluid may be normal in paediatric patients. Sedation was reversed.

The kitten was given glucose gel on recovery and recovered well with no complications.

Upon urine testing, the urine was mid-yellow and clear. Urine pH was 6.5 and the urine specific gravity (USG) was 1.025.

In neonatal patients, urine is isosthenuric until 10 to 12 weeks of age (Cohn and Lee, 2015), but usual reference ranges for healthy mature cats should be above 1.035 (Rishniw and Bicalho, 2015), so it was thought possible that the kitten suffered from some degree of renal impairment.

The urine was negative for protein, nitrite, blood, glucose, ketones, bilirubin, red and white cells, epithelial cells, casts, crystals, and bacteria.

The fluid drained from the cyst was identified by an external laboratory as poorly cellular cystic fluid with low numbers of red blood cells, occasional mildly activated macrophages, some containing phagocytosed red blood cells, and occasional small lymphocytes with rare neutrophils.

Fluid culture was negative, and no infectious agents were found. Fluid creatinine was 37µmol/L, which was a relatively low reading and not supportive of urine accumulation within the cyst, making a diagnosis of perirenal urinoma unlikely.

In the absence of ureterolithiasis or trauma, a congenital perirenal pseudocyst was considered the most likely diagnosis at this stage. Advanced imaging was recommended to search for underlying causes and make further recommendations for case management.

Differential diagnoses for perirenal or perinephric pseudocysts include renal neoplasia (lymphoma if bilateral, carcinoma if unilateral); hydronephrosis; perirenal cysts or haemorrhage; polycystic kidneys; renal haematoma; compensatory hypertrophy (if the other kidney is non-functional); and acute renal inflammation (usually associated with acute renal failure; Bainbridge and Elliott, 1996).

Perirenal pseudocysts are an accumulation of fluid in a fibrous sac around the kidney. The sac is not lined with epithelium, so not considered a true cyst. The fluid is usually a transudate, with very few cells (Bainbridge and Elliott, 1996), although one case has been reported secondary to transitional cell carcinoma where neoplastic transitional cells were found in cystic fluid and lining the cyst capsule (Raffan et al, 2008).

Three types of perirenal pseudocysts exist:

The cause of these cysts is unknown in the first two cases and not fully understood (Bainbridge and Elliott, 1996), although most patients have underlying renal disease. Cysts can occur at any stage of renal disease. This condition is very rare in the dog and more common in the cat. Older cats are predisposed, with a median age of 11 years (Beck et al, 2000), although rare cases have been described in kittens (Rothbrock, 2016).

At the next appointment, the kitten was doing well and had gained weight. However, the cyst was already beginning to refill following drainage and was the size of a passion fruit on abdominal palpation.

Repeated drainage was discussed. However, it was felt that repeated drainage was unlikely to be a long-term solution in such a young animal, as it would increase risk of an iatrogenic infection and might reduce the kitten’s quality of life.

Advanced imaging followed by surgery to resect and omentalise the cyst was recommended. Laparoscopic resection of perirenal pseudocysts has been performed with good results (McCord et al, 2008; Mouat et al, 2009), though was unfortunately not possible in this case for financial reasons. The owners were warned that the cyst could be associated with congenital renal impairment or other congenital abnormalities.

Unfortunately, the kitten was not insured, and referral was not an option. Resection of the cyst at the first opinion practice was offered with the understanding that, although several of the veterinarians at the clinic had done similar procedures, including nephrectomy, none of the vets had performed pseudocyst resection before.

Without advanced imaging, a risk existed that additional congenital abnormalities could be present.

The kitten’s owners decided to proceed with cyst resection at the first opinion practice. Risks were discussed prior to and during admission, including death, postoperative renal failure and postoperative ascites.

Pre-anaesthetic urinalysis and blood testing was performed, and the results were once again unremarkable except for the USG, which was 1.022 – low for a mature cat (Rishniw and Bicalho, 2015).

An intravenous catheter was placed and preoperative fluids were started at a rate of 2ml/kg/hr isotonic crystalloids (Hartmann’s solution). A premedication of 0.02mg/kg buprenorphine was given intramuscularly and intravenous propofol was given to effect to induce anaesthesia. The kitten was intubated and anaesthesia was maintained with inhaled isoflurane. Fluid rate was increased to 5ml/kg/hr during surgery.

The bladder was drained via cystocentesis. Active warming was provided using a temperature management system and the patient’s temperature was stable at 38°C throughout surgery.

A midline celiotomy was performed. The cyst was exposed and 20ml of straw-coloured fluid was drained through the cyst wall prior to capsule incision. No other abnormalities were detected. The capsule was removed using scissors until only a small amount of cyst lining remained. The capsule was avascular and minimal haemorrhage was observed. The mesentery was pulled over the ventral surface of the kidney and tacked to the cyst wall using 3-0 monofilament absorbable mattress sutures.

The diagram of omentalisation of a periprostatic cyst in Theresa Welch Fossum’s Small Animal Surgery (3rd edn; 2007) was a useful reference for this part of the procedure.

Following successful omentalisation, the kitten was spayed and microchipped. The midline incision was closed in three layers. Simple interrupted 3-0 monofilament absorbable suture was used in the muscle layer; a continuous pattern of the same suture material was used in the subcutaneous fat, and intradermal sutures were used in the skin.

Fluid rate was reduced to 3ml/kg/hr following surgery. Postoperative pain relief was provided with six-hourly intramuscular injections of 0.02mg/kg buprenorphine. NSAIDs were avoided due to the risk of renal impairment and no additional pain relief was necessary.

The kitten stayed in overnight for pain relief and further monitoring, and was discharged the next day. Ascites was not observed and no pain relief was required after the first 24 hours.

At a postoperative check three days post-procedure, no evidence of ascites was observed.

The wound was healing well and the kitten appeared clinically normal. One month post-surgery, the kitten had gained weight and had no palpable abdominal mass. Unfortunately, repeat blood and urine testing was not possible at this time.

Long-term prognosis is guarded due to the risk of chronic renal disease. Survival can be directly correlated to the degree of azotaemia at presentation (Beck et al, 2000).

Following cyst resection, hypertrophy of the unaffected kidney and associated increase in the glomerular filtration rate may compensate for decreased renal function in the affected kidney, which is unlikely to improve following surgery (McCord et al, 2008).

Repeat blood and urine testing, as well as SDMA values prior and post-surgery, would have provided more information regarding renal function, but were unfortunately not possible.

Potential complications after surgery include:

Following resection and omentalisation, the affected kidney continues to produce fluid which is absorbed through the omentum. Insufficient absorption of the fluid generated by the remaining cyst wall may cause ascites, although no ascites was seen in this case.

Perinephric cysts are commonly associated with chronic renal disease. Cyst resection will not prevent renal disease, although if the cyst is not drained or removed then increased pressure on the kidney and other abdominal organs by the cyst may cause renal function to deteriorate.

Due to the proximity of the cyst to the renal vessels, haemorrhage is a real risk, which may prove quickly lethal in small patients. The author found that good visualisation was easily achieved due to the low volume of perirenal fat.

Nephrectomy is not advised in most cases as it provides no benefits ,and greatly increases the intra and postoperative risk. However, it may be required in rare cases such as cyst formation secondary to chronic extravasation of urine (Geel, 1986) or hydrothorax (Rishniw et al, 1998), and the wise surgeon should be prepared for this possibility prior to surgery.

One case of hydrothorax secondary to perirenal pseudocyst has been reported (Rishniw et al, 1998). Intrapseudocystic scintigraphy confirmed a direct link between the pseudocyst and the pleural space. The hydrothorax improved following pseudocystectomy and unilateral nephrectomy.

In conclusion, this was an interesting and straightforward surgery well within the abilities of the average general practitioner.

Nephrectomy should be avoided if possible and a large incision is recommended to achieve good visualisation of the adjacent renal vessels. The cyst wall is generally avascular and little haemorrhage is expected.

A prolonged period of postoperative hospitalisation should not be required, although pre and postoperative monitoring of renal parameters is recommended.

Perirenal pseudocysts are generally associated with older feline patients, but the cyst in this kitten was thought to be congenital.