27 Nov 2017

Francesco Cian on the case of a dog with anorexia, lethargy, mild generalised lymphadenopathy and a history of travelling to Spain in the latest Cytology Corner.

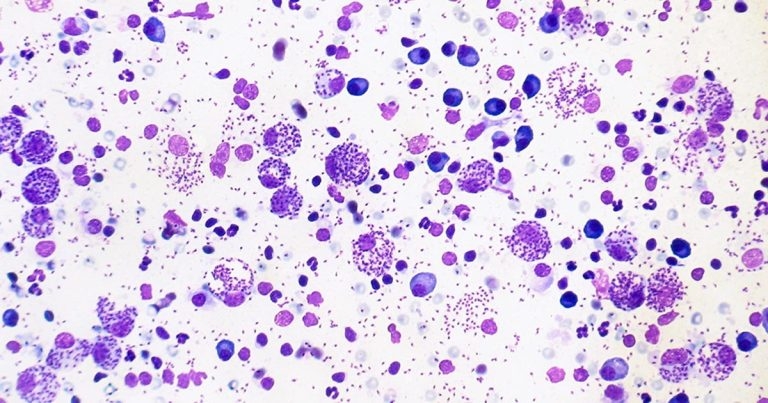

These images are from a lymph node aspirate of an adult male dog with anorexia, lethargy, mild generalised lymphadenopathy and a history of travelling to Spain (Wright-Giemsa, 10× to 50×). What is your diagnosis?

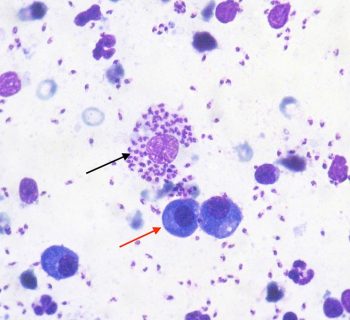

A mixed population of nucleated cells, mostly plasma cells (red arrow), is present, with lower percentages of macrophages (black arrow), small lymphocytes and a few neutrophils – the latter likely blood derived.

Plasma cells have a characteristic deep blue cytoplasm and occasionally show a clear perinuclear halo (Golgi zone); nuclei are round and eccentric, with granular chromatin.

Macrophages appear as large mononuclear cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, containing large numbers of intracellular organisms having a characteristic appearance of Leishmania species, also seen in the background.

The intracellular organisms (amastigotes) measure about 1.5 microns × 2.5 microns, and have a red nucleus and a characteristic bar-shaped kinetoplast.

These findings are consistent with plasma cell hyperplasia and macrophagic lymphadenitis with Leishmania species amastigotes.

The increased percentage of plasma cells in this lymph node aspirate is supportive of plasma cell hyperplasia – a condition characterised by the expansion of secondary lymphoid follicles after antigenic stimulation. The presence of large numbers of Leishmania amastigotes is indicative of infection.

Leishmaniosis is a vector-borne disease caused by a protozoan parasite spread by phlebotomine sandflies. The disease is endemic in several Mediterranean countries and cases in the UK may be observed in dogs with history of travelling in those areas.

The incubation period can vary from three months to several years, depending on the immune response of the individual animal. Dogs may present with a wide spectrum of clinical signs and clinicopathological abnormalities, ranging in severity from mild and self-limiting to fatal disease (for example, cutaneous lesions, enlarged lymph nodes and chronic kidney disease).

If a dog is examined because of clinical abnormalities compatible with Leishmania species, the vet should sample any accessible lesion to obtain cytologic smears or biopsies. If Leishmania species amastigotes are documented and the cytologic pattern is consistent with leishmaniosis, the dog should be considered infected.

Conversely, if cytology is negative, but the dog shows specific clinical signs, the presence of infection should be assessed by other tests, since cytology has been reported to have a low sensitivity for detection of the disease.

These tests include serology by immunofluorescent antibody test, ELISA and immunochromatographic test. PCR testing is also available – bone marrow, lymph nodes and spleen are the tissues with the highest potential prevalence for the detection by PCR. Whole blood can also be used; however, the sensitivity is lower than in the aforementioned tissues.