25 Sept 2017

Rosa Leedham reports on the case of an injured feline, which was discovered to be pregnant, and the effect this trauma had on it.

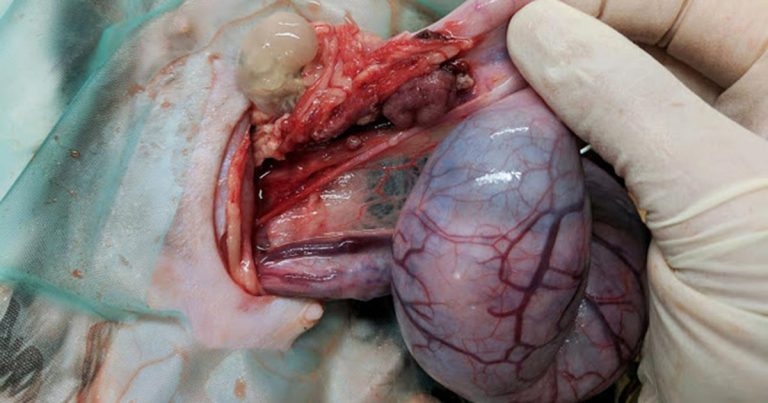

Figure 1. This thin white sac, composed of fetal membranes, had no immediate connection to the uterus.

A stray female domestic short-haired cat – non-weightbearing on the right hindlimb – was admitted to the RSPCA Greater Manchester Animal Hospital. The cat was approximately one year old, with no microchip or other form of identification. Other than lameness, no other clinical signs were present.

During physical examination under general anaesthesia, a midshaft clean femoral fracture was identified – presumably as a result of a road traffic collision. The cat was noted to be pregnant, identified by manual palpation. The fracture was subsequently repaired with an intramedullary pin and the patient recovered well postoperatively. No action was taken with regards to the pregnancy because the ownership status of the cat had not been determined at that point.

Seven days after admission, and still not claimed by an owner, the cat was anaesthetised again for a full clinical assessment and ovariohysterectomy in preparation for rehoming. The ventral midline laparotomy approach for the spay showed a moderate amount of serosanguinous fluid present in the abdomen. The cat was approximately six weeks pregnant, with four fetuses identified within the uterus, located in both horns. The left ovary was ligated as normal; however, the right ovary – the same side as the limb fracture – was certainly abnormal.

Extensive necrosis of fat was present in the right ovary region and a small, fluid-filled sac was present below the ovary. This thin white sac, composed of fetal membranes, had no immediate connection to the uterus (Figure 1). Within the sac was a small fetus that was significantly smaller than those within the uterus (Figure 2). The ovary was ligated below the sac and the remainder of spay performed as normal, although adhesions were present. The abdomen was flushed copiously with warmed sterile saline and the incision closed routinely.

An ectopic/extrauterine pregnancy is defined as the state when a pregnancy develops outside the cavity of the uterus. This can be classified based on the location of the fetus:abdominal, whereby gestation develops in the peritoneal cavity or oviductal whereby the oocyte is fertilised and remains in the oviduct (Corpa, 2006). This may be further defined as either primary or secondary.

When a fertilised oocyte enters the peritoneal cavity and becomes attached to the mesentery or abdominal viscera, this is defined as a primary ectopic pregnancy. The secondary form follows rupture of an oviduct or uterus after implantation and results in the expulsion of the fetus into the peritoneal cavity (Corpa, 2006).

The unusual presentation of this case is unlikely to be a primary ectopic pregnancy. It is presumed the road traffic collision that resulted in the limb fracture also caused the rupture of the uterine wall. This explains the presence of the fetus outside the uterus and, therefore, is best described as a secondary ectopic pregnancy.

Although well recognised in humans (Corpa, 2006), oviductal ectopic pregnancies are not observed in domestic animals due to the placental structure. However, this has been identified in rodents and lagomorphs; these animals possess a discoid haemochorionic placenta, which favours the development of a primary ectopic pregnancy (Dzięcioł et al, 2012). In fact, ectopic pregnancies are rarely diagnosed in animals given the absence of clinical signs in most cases and, therefore, it is usually an incidental finding (Osenko and Tarello, 2014).

Aside from the limb fracture, this cat appeared clinically normal. However, other case reports describe varying clinical signs, including anorexia, vomiting and retching, which are usually attributable to unrelated infections (Hannon, 1981), physical interference with organs in the abdominal cavity or necrosis of the ectopic tissue (Johnson, 1986). No clear relationship exists between the length of time an ectopic fetus is present in the abdominal cavity and the development of clinical signs (Corpa, 2006). In humans, a high incidence of fetal and maternal morbidity occurs during the first trimester (Tay et al, 2000).

Most pregnancies terminate due to haemorrhage, rupture of the oviduct or depletion of chorionic tissue (Nicosia, 1985). Similarly, it is usually the case abdominal fetuses do not survive in veterinary patients (Osenko and Tarello, 2014).

The number of ectopic fetuses can range from one to four, and the fetuses are usually mummified at the time of removal (Nack, 2000). Radiography and ultrasonography can be employed to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy. On a radiograph, an ectopic fetus would usually appear as a round, tightly curled outline visible in a location not normally associated with the uterus. The fetal bones may appear more radio-opaque with clear contrast due to a lack of fetal fluids (Thrall, 1994).

The difference in the size of the extrauterine fetus compared with the normal fetuses gives an indication as to the timing of the traumatic event, whereby the trauma was likely one to two weeks before the spay was performed in this case (Figure 3).

Unplanned pregnancies are common in cats. The author’s workplace urges vets to consider the reproductive status of all female cats when evaluating trauma cases. A paucity of studies are available evaluating the epidemiology of ectopic pregnancies in cats, likely attributable to the absence of clinical signs in most cases.