18 Sept 2017

Mike Davies summarises a study he conducted that looked into the role and impact of edible seeds and grains in canine diets.

Cereals are the edible seeds or grains of the grass family Gramineae and include wheat, barley, maize, oats, rye, Sorghum and rice.

They have been incorporated into dog food for many years and are sources of energy, carbohydrate, protein and fibre, as well as micronutrients such as vitamin E, B vitamins, magnesium and zinc (McKevith, 2004).

Many dog owners have acquired a perception that health risks are associated with feeding grain to dogs, so they actively avoid giving food containing grains. In response, several companies now manufacture and actively promote “grain-free” foods as providing a health benefit. While filming a TV programme for the BBC at a toy breed championship show in Stafford in April, the author became aware many breeders in attendance believed feeding food containing grain was associated with tear staining in their dogs.

An excellent overview of the nutritional aspects of cereals has been published by the British Nutrition Foundation (McKevith, 2004), but no such review has been conducted specifically on their role in dog nutrition and health. This article will summarise the results of a review the author has just completed.

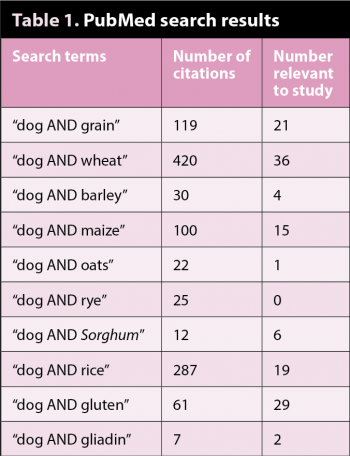

An online literature search was performed to determine the scientific evidence to support health benefits or risks of feeding grain to dogs. PubMed was searched using these terms:

The number of citations returned and the number that were relevant are in Table 1.

A total of 98 individual papers reported studies involving dogs and grains, and their effect on nutrition, gastrointestinal function or disease. A full meta-analysis of the papers was not feasible because the studies reported different topics, used different methodologies and, for some, the number of dogs involved was low, reducing statistical power.

Other studies were identified – for example, those about the effects of the extrusion cooking process from separate online search engines including Google.

Claims grains can affect digestibility of other components of the diet are correct. The presence of cereal grain – notably fibre (Fahey et al, 1990) or phytate components – can reduce digestibility of a ration, for example, fats, dry matter and energy (Bazolli et al, 2015; Beloshapka et al, 2014; Merritt et al, 1979; Pacheco et al, 2014; Swanson et al, 2004; Adolphe et al, 2012; Panasevich et al, 2015; de Godoy et al, 2014; Goudez et al, 2011; Guevara et al, 2008; Gajda et al, 2005; Murray et al, 1999; Carciofi et al, 2008; Twomey et al, 2002).

However, for other components, digestibility may not be affected (Beloshapka et al, 2014; Panasevich et al, 2015; de Godoy et al, 2014).

Providing the dog is being fed a balanced diet with sufficient amounts of essential nutrients, as recommended by the European Pet Food Industry Federation to account for any reduced bioavailability, health should not be compromised, and no case reports of nutritional deficiency-related disease due to the presence of cereal in a complete dog food was found.

Claims domesticated dogs cannot digest cereal grains and should be fed only a carnivorous meat-based diet “like wolves” are not substantiated by the evidence.

Firstly, through evolution, domesticated dogs are significantly genetically different to wolves – including three gene changes that facilitate digestion and use of starches. Indeed, most dog sequences belong to a divergent monophyletic clade sharing no sequences with wolves (Axelsson et al, 2013; Pang et al, 2009; Tonoike et al, 2015; Vilà et al, 1997).

Secondly, the ability of domesticated dogs to digest and use grains (including the starch they contain) has been demonstrated in numerous in vivo and in vitro studies (Brown et al, 2009; Carciofi et al, 2008; Murray et al, 2001; Bednar et al, 2001; Pouteau et al, 1998; Walker et al, 1994) including in dogs with enteropathy (Breitschwerdt et al, 1992).

For claims cereals are a poor source of protein, wheat gluten did not perform well in protein efficiency ratio calculations in dogs, showing it is a relatively poor protein source for immature dogs, compared to soy and casein (Burns et al, 1982).

However, corn gluten proved to be a better supplier of protein to growing puppies than a poor poultry meal product (Case and Czarnecki-Maulden, 1990) and, compared to other vegetable protein sources, wheat products were characterised by a relatively greater release of amino acids threonine, isoleucine and histidine (Savoie et al, 1989).

Overall, studies have shown protein digestibility is not adversely affected by the presence of cereals and fibre, nor is growth in puppies or blood cell regeneration in dogs with anaemia (Beloshapka et al, 2014; Delorme et al, 1985; Whipple et al, 1951). Some cereal products – for example, gluten – increase branch-chained amino acid content (Nogata and Nagamine, 2009).

Wheat gluten digestibility can be better than poultry meal and it improved faecal quality in dogs – especially in large dogs known to be sensitive to dietary intake (Nery et al, 2012). When added to the ration, wheat bran had no effect on protein efficacy (Delorme et al, 1985), and in basenjis with protein-losing enteropathy, cereals did not adversely alter digestibility of the ration or faecal consistency (Breitschwerdt et al, 1992).

Most cereal-based dog foods are produced by a manufacturing process called extrusion, which may change carbohydrates, dietary fibre, the protein and amino acid profile, vitamins and mineral content in a manner that is beneficial or detrimental (Beaufrand et al, 1978; Guy, 2001).

Positive effects include:

Negative effects include:

Vitamin and amino acid losses are minimised during high-temperature extrusion for a short duration, and this may also improve protein quality and digestibility, as well as affect shape, texture, colour and flavour.

Nutritional quality has been found to improve with moderate conditions (short duration, high moisture and low temperature), whereas a negative effect on nutritional quality of the extrudate occurs with a high temperature (at least 200°C), low moisture (less than 15%) or improper components in the mix (Harper, 1978).

No reports of nutritional deficiency or other health problems were reported attributable to the extrusion process following the feeding of a complete cereal-based dog food.

A lot of studies have been published on dogs with confirmed familial gluten-sensitive enteropathy due to single autosomal recessive (notably from one family of Irish setters).

Fortunately, the gastrointestinal changes in structure and function that occur and clinical signs can be reversed by feeding a gluten-free diet, and known at-risk individuals can be prevented from developing the disease if challenged later, by avoidance of exposure to gluten from birth (Batt et al, 1985; Garden et al, 1998, 2000; Manners et al, 1998a,b; Pemberton et al, 1997; Lowe et al, 1995; Hall et al, 1992; Hall and Batt, 1990a-c, 1991a,b, 1992).

Exposure to gluten has also been associated with neurological signs (cramping) in border terriers (Lowrie et al, 2015) and one case study by Lowrie et al (2016) described a border terrier with multisystem clinical manifestations that responded to a gluten-free diet. This dog had a combination of neurological signs, skin disease and signs suggestive of gastrointestinal disease with pathological changes in the gastrointestinal tract, and positive serological results for transglutaminase 2 IgA and anti-gliadin IgG – all of which responded to a gluten-free diet.

While the authors’ findings do not confirm a definite role for gluten in the multisystem signs shown in this case, the evidence is compelling, as the neurological signs occurred in the postprandial period, all signs resolved following removal of gluten from the dog‘s daily ration and because of similarities to the human condition (Davies, 2016). While true prevalence rates are not known, these gluten-related disorders are rarely reported. In soft-coated wheaten terriers with protein-losing enteropathy and/or protein-losing nephropathy, gluten was shown not to be the cause (Vaden et al, 2000a); however, in another study (Vaden et al, 2000b), some affected dogs did react to exposure to corn or farina cream of wheat, as well as other dietary components.

While gluten was reported in one study to be associated with anaemia following vigorous exercise (Yamada et al, 1987) racing huskies fed a meat-free, cereal-based diet did not develop anaemia – indeed, red cell count and haemoglobin increased significantly over time (P<0.01; Brown et al, 2009) and in animals with induced anaemia feeding gluten increased blood protein levels (McNaught et al, 1936; Pommerenke et al, 1935; Whipple et al, 1951).

High gluten-containing diets have been moderately associated with loss of lean muscle mass (Wakshlag et al, 2008), which is attributable to its lack of some essential amino acids (lysine and tryptophan) and chicken protein is better at regulating protein degradation than corn gluten meal (Helman et al, 2003).

Allergies involving dermatological or gastrointestinal signs have been reported following exposure to cereals (Jackson et al, 2003; Paterson, 1995) although the most frequent of these (wheat-related allergies) account for only about 13% of all dietary allergy cases, and are less common than allergies to other food components, such as beef, dairy products and chicken (Mueller et al, 2016; Mueller et al, 2000; Vaden et al, 2000a; Jeffers et al, 1996).

In some cases in which cereal-based foods caused signs, these may actually be due to nutritional deficiency/imbalance, rather than a true allergic response (Sousa et al, 1988). In one study, a diet containing corn starch did not exacerbate skin lesions or itchiness in dogs known to have hypersensitivity to corn (Olivry et al, 2007).

Some rice-containing diets have been implicated in the development of taurine deficiency and dilated cardiomyopathy in dogs (Delaney et al, 2003; Backus et al, 2003; Fascetti et al, 2003).

However, more recent studies (Ko and Fascetti, 2016; Tôrres et al, 2003) have shown the rice component is unlikely to be the cause, whereas the presence of other dietary components might be.

Mycotoxin contamination of cereals can occur and aflatoxins can cause disease and death in dogs (Wouters et al, 2013; Bruchim et al, 2012; Leung et al, 2006; Pestka and Smolinski, 2005; Golinski and Nowak, 2004).

Contamination with Aspergillus was detected in poorly stored cereals, but not found in dry pet foods (Campos et al, 2008). It had been suggested zearalenone – a toxin produced by Fusarium moulds that can contaminate poorly stored cereals – has oestrogenic properties and could interfere with bitches’ hormonal cycle (Golinski and Nowak, 2004); however, any clinical relevance of this has yet to be demonstrated.

Wheat gluten contaminated with melamine (a serious toxin) by Chinese producers was responsible for thousands of dog fatalities due to acute kidney injury in North America (Dobson et al, 2008).

This is thought to have been a deliberate act to artificially increase the protein content on chemical analysis, and so increase the market value of the product.

Historically, dogs fed home-made, exclusively cereal-based diets deficient in niacin would develop niacin deficiency, or “black tongue” (Belavady and Gopalan, 1965). Signs included:

Additional clinical information is courtesy of www.provet.co.uk

This condition is extremely rare and would only occur if a dog is fed a totally inappropriate deficient home-made diet.

No evidence was found to support an association between tear staining and the consumption of grain-containing dog foods.

Wheat gluten contains angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides (Nogata et al, 2009) and also opioid-active peptides (Schick and Schusdziarra, 1985; Schusdziarra et al, 1981), which could alter physiological processes, such as plasma insulin and glucagon concentrations, and play a role in disease – but this has yet to be demonstrated.

The presence of wheat bran or other grains may lower serum cholesterol (Swanson et al, 2004; Sharma et al, 1980) – a potential health benefit.

Food ingredients can affect diagnostic tests. In one study, dry cereal-based diets reduced occult blood detection compared to meat-based canned foods (Rice and Ihle, 1994).

Cereal-based grain-containing foods provide energy and other nutrients for domesticated dogs that have evolved to be able to digest and use them. Some specific diseases can be associated with the presence of some grains, including gluten sensitivity, resulting in gastrointestinal or possibly multisystemic signs, and dietary allergies, causing gastrointestinal or dermatological signs. However, the prevalence of cereal-based dietary allergies is low, confirmed gluten sensitivity is very rare and these conditions resolve by removing exposure to the cereal involved.

Inadequate scientific evidence exists to support the recommendation for widespread feeding of grain-free diets to dogs.