3 Jan 2023

James Smith BVSc, MSc, CertAVP(GSAS), PGCertSAOphthal, MRCVS suggests options for repositioning the third eyelid rather than excising it.

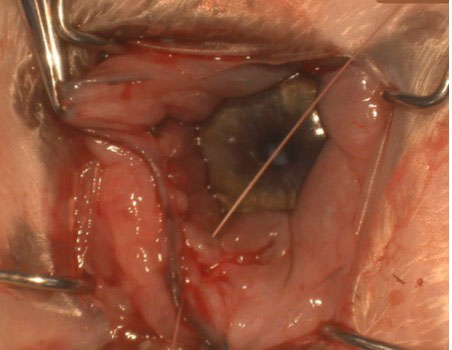

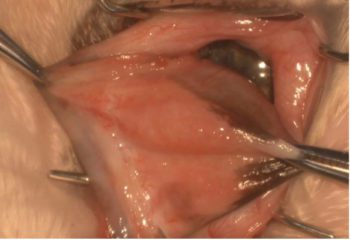

Figure 1. Prolapsed third eyelid gland in an 11-month-old English bulldog, presenting four days after initial prolapse.

Why do we consider cherry eye to be a re-emerging problem?

Anecdotally, within the UK referral population, colleagues are seeing an increasing number of English bulldogs with keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) that is refractory to medical management, which have had their third eyelid glands excised.

Factors that may be influencing this increasing caseload within referral practice include the popularity of breeds at risk of prolapse of the nictitating gland (PNG), such as the English bulldog; the perceived complexity and cost of surgical repositioning compared to excision; lack of available surgical training; and the upsurge of veterinary fertility clinics, which offer surgical excision of the PNG as a first-line treatment.

Whatever the cause, by the time these cases are referred, significant impacts have often been made on patient vision, as well as financial implications for the owner.

PNG is commonly referred to as “cherry eye” by owner and vet alike. The exact pathogenesis of the condition is not fully understood; however, it is thought to be a combination of a weakening of the connective tissue attachments of the gland to the ventral periorbital tissues, and lymphoid hyperplasia, leading to subsequent prolapse beyond the leading edge of the nictitating membrane (Morgan et al, 1993; Peruccio, 2018; Hartley and Hendrix, 2021).

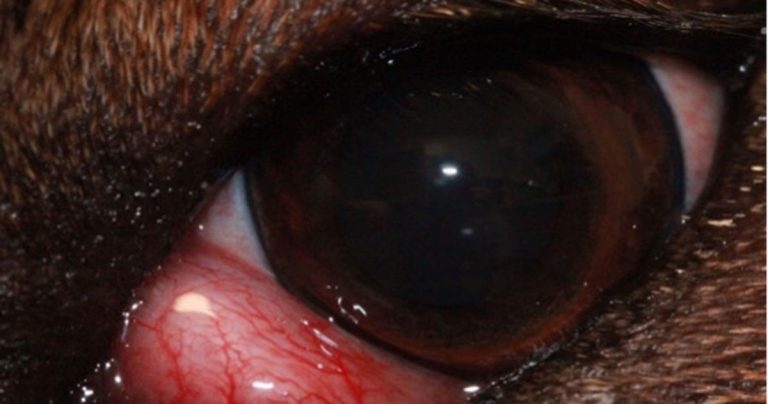

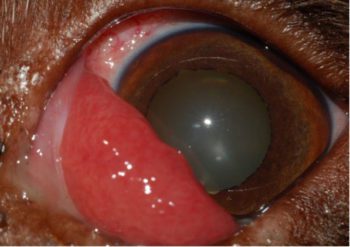

Once prolapsed, the gland can become traumatised, causing irritation to the patient and some degree of anxiety to the client. Clinically, it appears as a fleshy pink protuberance at the medial canthus. Early on, it will likely appear lustrous and healthy (Figure 1); however, without appropriate repositioning or use of topical lubricants, continued trauma can lead to a much more inflamed appearance (Figure 2).

Several breeds are known to be predisposed to PNG, including the cocker spaniel, Boston terrier, Pekingese, beagle, Lhasa apso, shih-tzu and English bulldog (Dugan et al, 1992; Morgan et al, 1993; Hartley and Hendrix, 2021).

Excision of the exposed portion of the gland was previously advocated; however, it has long been recognised that the nictitans gland contributes a significant proportion of the aqueous pre-corneal tear film (approximately 35%; Gelatt et al, 1975).

In addition, many of the breeds predisposed to PNG are also considered at increased risk of developing KCS (Table 1). Therefore, retention of the gland is preferable to its excision in almost all cases.

Excision of, or failure to reposition, the gland can lead to an increased incidence of KCS (68.4% and 15.8%, respectively) compared with those eyes in which the gland was replaced (10.5%; Morgan et al, 1993).

Excision should, therefore, only be considered as a procedure of last resort; for example, irreparable trauma or underlying neoplasia.

Several techniques exist that are described to facilitate repositioning of the prolapsed gland. Broadly, they can be separated into two groups: the conjunctival pocketing techniques and the anchoring techniques.

Morgan’s pocket, or a modification of this procedure, is considered the most commonly used technique for the replacement of a PNG. This technique is effective in achieving successful repositioning of the gland, with a reported failure rate of between 1% and 7% (White and Brennan, 2018) across all breeds; however, appropriate training and use of magnification are advised, as the technique can prove challenging for inexperienced surgeons.

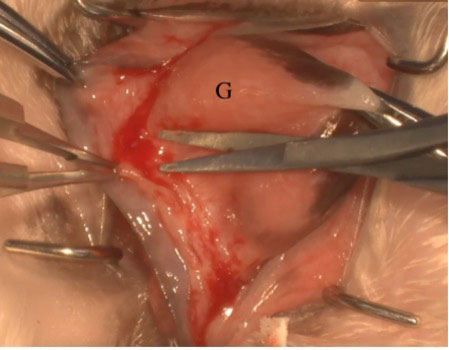

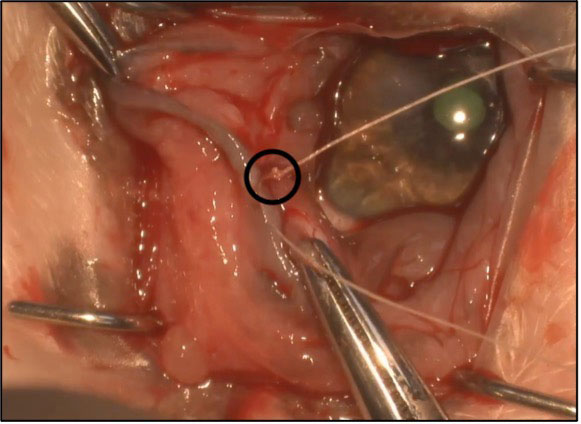

The nictitating membrane is protracted using either stay sutures or thumb forceps to expose the posterior bulbar conjunctiva (Figure 3).

Two semi-circular conjunctival incisions – the first anterior and the second posterior – to the prolapsed gland are made using either a Bard-Parker number 15 scalpel or Beaver number 6400 blade.

It is important that the two incisions do not meet at either end (Figure 4).

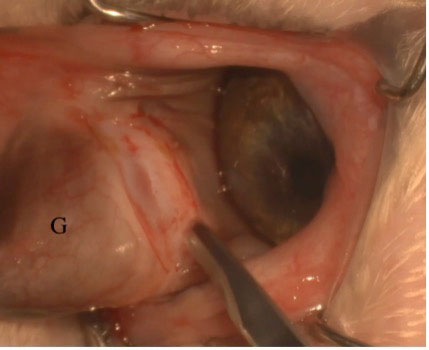

The bulbar conjunctival caudal to the gland is then elevated from the underlying connective tissue and a deep conjunctival pocket can be created by blunt dissection down towards the ventral rectus muscle insertion (Figure 5).

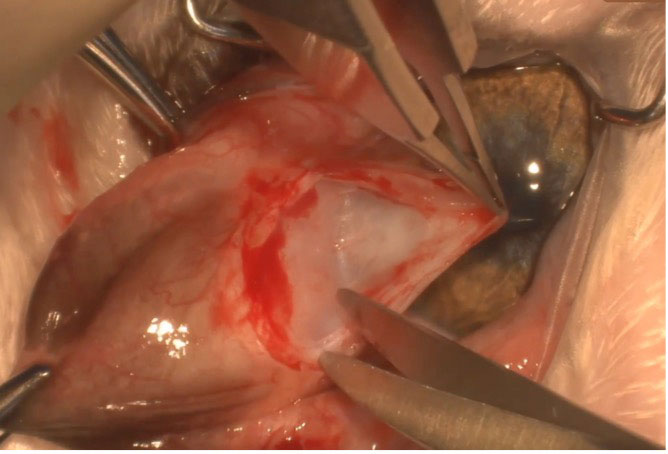

The conjunctival edges can then be advanced over the exposed gland, which is repositioned within the created subconjunctival pocket, and apposed using either 5-0 or 6-0 polyglactin in a simple continuous fashion (Figure 6), ensuring the suture knots are positioned on the anterior aspect of the nictitating membrane.

1. Placement of stay sutures through the superior and inferior aspects of the nictitating membrane, and through the PNG, allow tissue manipulation with reduced trauma.

2. Make the conjunctival pocket as large and as deep as possible to reduce tension on the conjunctiva following closure of your incision. This will help to reduce the risk of wound dehiscence and surgical failure.

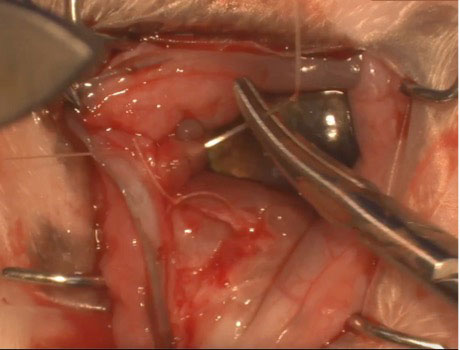

3. Once the subconjunctival pocket has been dissected and PNG has been repositioned within this pocket, place a single simple interrupted suture in the middle of the two incisions closing the pocket. This makes the next phase of suturing the pocket closed using a continuous suture pattern much easier due to the lack of tension. This stay suture is then removed as the pocket is closed (Figure 7).

4. Take reasonably large bites of conjunctival tissue within the suture line to reduce the risk of the suture material tearing through the conjunctiva.

It is also important to ensure both ends of the incision are left open to allow continued drainage of nictitating membrane gland secretions.

The anchoring techniques can be separated into the inferior scleral anchor, the periosteal anchor, and the ventral rectus anchor. Each of these techniques relies on the tying down of the nictitating membrane gland to a structure adjacent to its normal position. Two further techniques described are the intra-nictitans tack and the peri-limbal pocket (Plummer et al, 2008; Prémont et al, 2012).

The technique chosen is not as important as the surgeon’s familiarity with the procedure. Complications are much more likely to arise attempting a procedure that you are unfamiliar with as opposed to one in which you have received training and completed previously.

Potential complications associated with surgical repositioning include recurrence of prolapse, conjunctival cyst formation, reduced mobility of the nictitating membrane and corneal ulceration (Plummer et al, 2008; White and Brennan, 2018).

In the author’s experience, the Morgan’s pocket technique is favoured in the majority of first-time prolapses and those breeds that are not at an expected increased risk of PNG recurrence. In breeds which have a reported higher-than-average rate of recurrence (English bulldog and mastiff breeds; White and Brennan, 2018), or have already undergone multiple surgeries, a three-step combination procedure is used.

Firstly, a deep conjunctival pocket is created, then the gland is anchored to the ventral rectus muscle using a single non-absorbable suture, before the pocket is then closed and then over-sewn.

At the time of writing, no cases having undergone this procedure have suffered with recurrent PNG.

Following gland replacement, postoperative treatment consists of oral NSAIDs and topical antibiotics.

The provision of an Elizabethan collar to prevent self-trauma is also recommended.

The use of topical corticosteroids is often contraindicated as healing may be retarded, leading to possible wound dehiscence and repeat prolapse of the gland. However, their use can be justified in those cases of persistent conjunctival and third eyelid swelling following healing of the conjunctival incision. Conversely, a preoperative topical steroid has been advocated to reduce inflammatory gland hypertrophy, which may improve success rates (Ramsey, 2008; Rankin, 2013).

As veterinarians, we must continue to educate the pet-owning public, as well as the breeding fraternity where possible; ensure our surgical technique is good; and record within the clinical history whenever owners go against veterinary advice (resection rather than reposition).

Referral is always an option; however, with good teaching and appropriate equipment, surgery to replace a prolapsed nictitating membrane gland can be completed successfully within first opinion practice.

Replacing a prolapsed gland is almost always our preferred option, despite its perceived challenges. If this is not possible, then leaving the nictitating membrane gland in situ may be the better option.