5 Sept 2023

Sergio Silvetti details the case of an eight-year-old female mustelid that was diagnosed with extrahepatic biliary obstruction.

Photo by Verina

This case describes the diagnosis and treatment of a ferret referred for investigations of elevation of liver biochemical parameters and persistent icterus. Abdominal ultrasound allowed a diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary obstruction to be made.

The distal biliary duct obstruction was relieved by choledochotomy and manual removal of the inspissated biliary content, followed by cholecystectomy due to noted abnormalities in the gallbladder and its content. The ferret recovered well from the procedure, and the icterus waned during the following days.

Liver problems in ferrets are not uncommon, but the disease is often subclinical. Exploratory laparotomy with biopsy often remains the best diagnostic tool to confirm hepatic malfunction suspected based on haemato-biochemical and ultrasonographic abnormalities. Surgical exploration should be considered in cases where imaging findings are indicative of obstruction or in cases where the medical treatment is unable to improve patients’ conditions.

Gallbladder pathology in ferrets is not commonly described, but cholecystitis, gallbladder stones, extrahepatic biliary tract obstruction (EHBO) and neoplasia are all entities reported to affect the gallbladder and the bile duct in this species (Hoefer et al, 2012).

Aleutinian disease can also cause bile duct proliferation, arteritis and progressive wasting, with bile duct hyperplasia and periportal fibrosis common findings in these cases (Morrisey and Kraus, 2012).

Hepatic pathology is not uncommon in ferrets, but the disease is often subclinical. Biopsy often remains the best diagnostic tool to confirm hepatic malfunction based on haemato-biochemical and ultrasonographic findings, and to gain information on the underlying processes affecting the liver (Hoefer, 2021).

Surgical exploration is indicated in cases where imaging findings are indicative of clear obstruction or in cases where the medical treatment is unable to improve patients’ conditions (Hoefer, 2021). It should be considered that the liver and the biliary system anatomy in ferrets differs significantly from that in dogs and cats (Evans and Quoc, 2014).

In ferrets the liver has six lobes and, proportionally, a ferret’s liver is larger than a dog’s, equating to 4.3% of bodyweight compared to 3.4% in dogs.

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ that sits in the fossa between the quadrate and right medial liver lobes. The average volume of bile contained within the gall bladder is 0.5ml to 1ml, and this drains via the cystic duct, which joins the left, right and central hepatic ducts forming the common bile duct, although variations exist (Evans and Quoc, 2014).

The liver is the largest solid gland in the body. It is responsible for the metabolism of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates, as well as storage of vitamins, and is also involved in the transformation of vitamin D to its metabolically active form, removal of waste products (such as ammonia, bilirubin and some medications) and the production of bile salts.

The function of the gallbladder is to store and then expel the bile in response to neuro-endocrine signals, predominantly relating to lipid content in ingested food (Akers and Denbow, 2013).

| Table 1. Blood results received from the referring vet. Clear evidence exists of hepatic suffering and mild dehydration; the mild neutrophilia was considered either stress related or a response to an infectious agent | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Laboratory value | Reference ranges |

| Alb (g/l) | Icteric serum | 25-41 |

| ALP (UI/l) | 219 | 15-75 |

| ALT (UI/l) | >2000 | 13-176 |

| Amy (UI/l) | 14 | 26-36 |

| TBil (µmol/l) | 298 | 3.42-8.55 |

| BUN (mmol/l) | 7.2 | 1.90-7.49 |

| Crea (µmol/l) | Icteric serum | 0-75 |

| TCa (mmol/l) | 2.55 | 1.2-2.94 |

| Pho (mmol/l) | 2.14 | 1.29-2.94 |

| Glu (mmol/l) | 5.3 | 5.18-11.41 |

| Na+ (mmol/l) | 145 | 137-162 |

| K+ (mmol/l) | 5.6 | 4.3-7.7 |

| TP (g/l) | Icteric serum | 51-74 |

| Glob (g/l) | // | |

| Haematology | Laboratory value | Reference ranges |

| RBC x1012 | 10.65 | 7.0-13 |

| Hgb (g/dl) | 21.1 | 12.0-18.7 |

| HCT % | 51.15 | 36-56 |

| MCV (fl) | 48 | 40-48 |

| MCH (pg) | 19.8 | 13.5-16.5 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 41.3 | 32.1-35.5 |

| TWBC x109 | 7.21 | 2-10 |

| Neut x109 | 6.03 | 0.8-4.5 |

| Lymph x109 | 1.12 | 0.4-6.5 |

| Mon x109 | 0.06 | 0.1-0.7 |

| Eos x109 | // | 0-7 |

| Bas x109 | // | 0-2 |

| Neutr % | 83.6 | |

| Lymph % | 15.5 | |

| Mon % | 0.8 | |

| Eos % | // | |

| Bas % | // | |

| PLT x109 | 595 | 96-776 |

| PCT % | 0.45 | |

| MPV fl | 7.6 | |

An eight-year-old female, neutered ferret was referred for investigation of weight loss, anorexia and jaundice lasting for two days prior to presentation.

A blood profile, including haematology and biochemistry, was performed by the referring veterinarian and marked elevation of alanine aminotransferase and total bilirubin (TBil) was detected, with haematological parameters within normal limits.

Unfortunately, some biochemistry parameters were not able to be tested (creatinine, total proteins, albumins and globulins) due to interference by the discolouration of the icteric serum (Table 1).

Prior to being seen by our clinic, the ferret was treated with injectable penicillin, followed by a course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid treatment and prednisolone tablets, followed by ursodeoxycholic acid as well as metoclopramide (unknown if oral or injectable) and SC fluid treatment.

Unfortunately, no doses have been reported with the referral form.

On presentation, the ferret weighed 0.52kg and was responsive, but lethargic. An obvious jaundice was evident on examination of the skin, mucous membranes and sclerae. Dehydration was estimated to be 5% to 7% during clinical examination and abdominal palpation was unremarkable.

The ferret was admitted for rehydration and supportive care overnight, with an abdominal ultrasound scan scheduled for the following day. The left cephalic vein was cannulated and IV fluids were administered at 4mls/kg/hour. Oral treatment, with the medications dispensed by the referring veterinarian, was also continued in the hospital.

The abdominal ultrasound was performed by a colleague certified in cardiology and diagnostic imaging with the conscious patient. The ultrasonography diagnosed the enlargement of the cystic duct; the left, right and central hepatic ducts; and the common bile duct, with an occlusion caused by echogenic material in the distal portion of the duct with slight protrusion of the sphincter of Oddi into the duodenal space. Also, a thickening of the gallbladder walls with thickened gallbladder’s content was found.

The ferret was sedated with medetomidine 0.1mg/kg, butorphanol 0.3mg/kg and ketamine 5mg/kg by IM injection, and prepared for exploratory laparotomy. The patient was induced with isoflurane 2% in oxygen via face mask and intubated after local anaesthesia of the glottis with lidocaine spray with a 2.5mm uncuffed Cole tube.

Anaesthesia was maintained throughout the surgical procedure with isoflurane 2% to 2.5% delivered in 100% oxygen. The IV fluid rate was increased to 10ml/kg/hour during surgery. An SC injection of 50/50 diluted lidocaine 2% and sterile water for injection was used as a linear local anaesthesia block for the incision site as part of multimodal analgesia.

A midline incision was made from the xiphoid cartilage to 2mm caudal to the umbilicus, and an abdominal wall retractor was used to improve visibility of abdominal cavity.

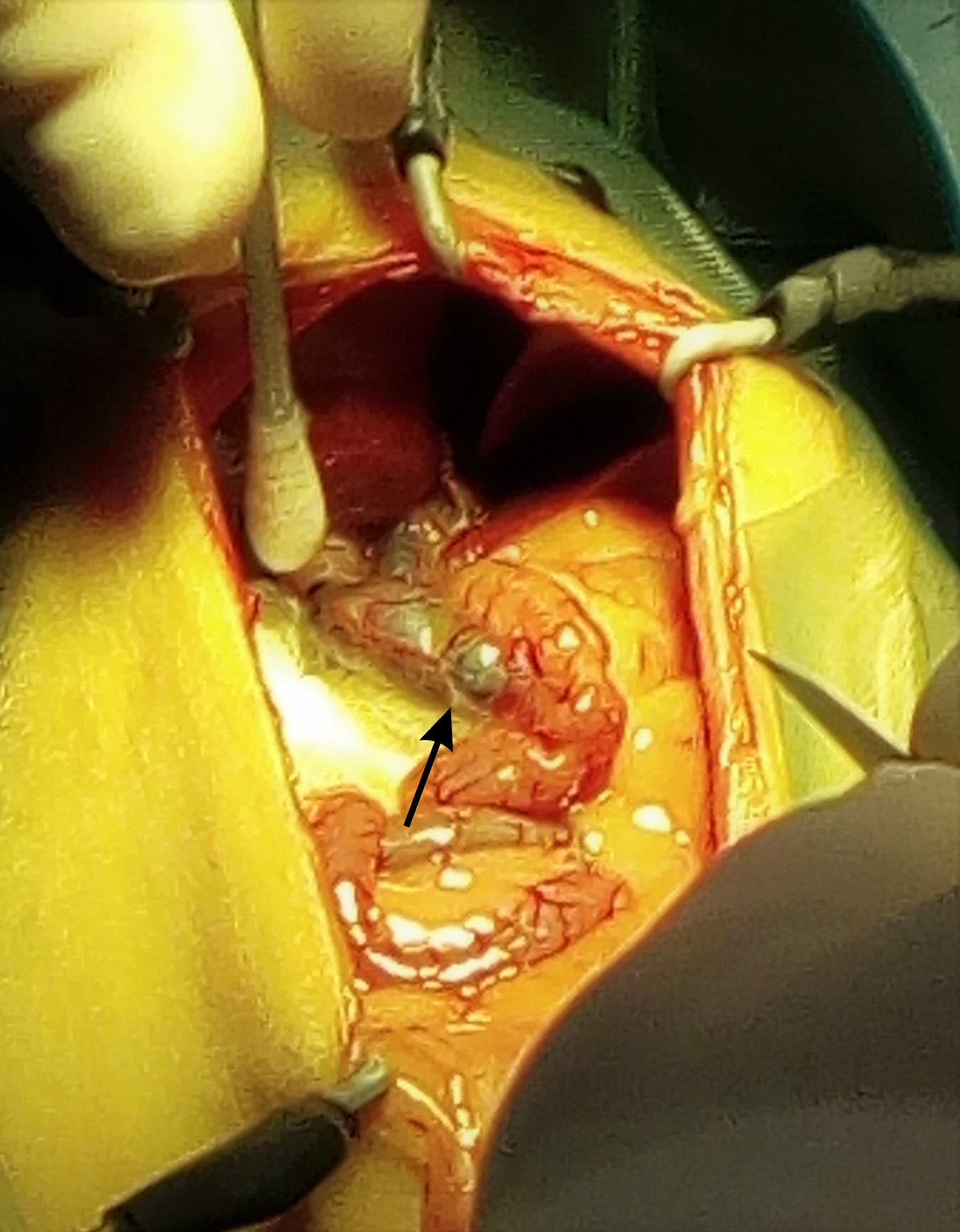

The liver appeared of normal shape and size, but a diffuse jaundice (icterus) of the hepatic parenchyma (Figure 1), abdominal cavity and intra-abdominal fat was evident (Figure 2). The gall bladder was distended with tortuous and visibly enlarged hepatic and extra-hepatic bile ducts (Figure 3).

The abdomen was packed with sterile gauze swabs moistened with saline to isolate the distal portion of the enlarged extrahepatic duct (Figure 4) to minimise potential abdominal contamination of extravasated bile.

A choledochotomy was carried out on the distal portion of the common duct and a large amount of crystallised proteinaceous material was removed using a small Volkmann spoon. The duct was then cannulated with a 4F TomCat catheter without stylet and flushed with warm sterile solution to assess the patency of duodenal papilla and to remove any remaining material in the proximal duct.

The cannulation proved successful for clearing the distal duct, but the content of the proximal portion required manual expression, followed by flushing. The common bile duct was then closed with interrupted sutures of poliglecaprone 5/0 and leak-tested with an injection of 0.2ml of warm sterile solution using a sterile 0.5ml insulin syringe with a 30G needle.

The gallbladder was then inspected and an attempt to express the content was made, but proved unsuccessful. A decision was made to perform a cholecystectomy.

The gallbladder was bluntly dissected from the surrounding hepatic parenchyma and bleeding was controlled with sterile collagen compresses.

The gallbladder was then removed after simple ligation of the cystic duct with poliglecaprone 4/0. A liver biopsy was also obtained by a guillotine suture of poliglecaprone 4/0 from the edge of the quadrate lobe.

A further abdominal inspection revealed a mildly enlarged left adrenal gland, enlarged spleen and two areas of apparent fibrosis on the left kidney.

Prior to closure, the abdominal cavity was flushed several times with warm sterile fluids and the abdominal wall was closed with polydioxanone 3/0 in a continuous mattress pattern. The skin was then sutured with poliglecaprone 4/0 using an intradermal continuous pattern.

The recovery was slow, but stable and the patient was hospitalised overnight with continuation of IV fluids at 4ml/kg/hour. Ongoing analgesia was provided with oral tramadol at 10mg/kg every 12 hours and meloxicam at 0.2mg/kg every 24 hours.

Oral antibiotics were continued with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid at 12.5mg/kg and metronidazole at 20mg/kg, both every 12 hours. Oral ranitidine at 2mg/kg every 12 hours was also started. Supportive nutrition was also started two to three hours after the full recovery from anaesthesia with carnivore care food.

The following morning the patient was much brighter, taking liquid food well and keen to eat on her own. Once feeding resumed, IV fluids were discontinued and the patient was discharged later the same day.

The patient presented back two days later for signs of lethargy, anorexia and lack of faecal production. The patient was quieter than normal and responsive to external stimuli, but lethargic. Jaundice was still present, along with some discomfort, and an intra-abdominal swelling was identified on palpation, localised to the right cranial abdomen.

Hospitalisation was recommended, but declined by the owner. Tramadol dose was reduced by 50%, syringe feeding was continued and oral lactulose was introduced to reduce the possible development of post-surgical hepatic encephalopathy (American Liver Foundation, 2019) and for its laxative effect. The ferret improved over the following 24 hours.

The gallbladder was sent to an external laboratory for microbiology and histopathology. Histopathology identified cholecystic ectasia with mucosal hyperplasia, hepatocellular atrophy, mild multifocal neutrophilic hepatitis, biliary hyperplasia and intracanalicular cholestasis.

No bacteria were isolated on aerobic or anaerobic culture.

The patient was seen for a second postoperative check-up 10 days after the surgery. The surgical wound was completely healed, the ferret was alert and active, and appetite and defecation were normal.

An ultrasound was performed and revealed normal liver parenchyma, but still a significant distension of the intra-hepatic bile ducts without any clinical signs. Analgesia and antibiotic treatments were stopped, but ursodeoxycholic acid treatment was started at 10mg/kg every 12 hours despite the disappearance of jaundice with the aim of reducing the biliary stasis and to prevent further occlusion.

| Table 2. A general improvement of the hepatic enzymes is evident, slightly reduced haematology parameters due to improved hydration. To be noted that several parameters and electrolytes are missing due to the choice of a reduced ferrets screening because the limited economic availability of the owner |

||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Laboratory value | Reference ranges |

| Alb (g/l) | 34 | 25-41 |

| ALT (UI/l) | 83 | 13-176 |

| TBil (µmol/l) | 7.3 | 3.42-8.55 |

| BUN (mmol/l) | 7.6 | 1.90-7.49 |

| Crea (µmol/l) | 27 | 0-75 |

| Glu (mmol/l) | 8.89 | 5.18-11.41 |

| TP (g/l) | 82 | 51-74 |

| Glob (g/l) calculated | 48 | |

| Haematology | Laboratory value | Reference ranges |

| RBC x1012 | 7.07 | 7.0-13 |

| Hgb (g/dl) | 12.2 | 12.0-18.7 |

| HCT % | 37.6 | 36-56 |

| MCV (fl) | 53.7 | 40-48 |

| MCH (pg) | 17.2 | 13.5-16.5 |

| MCHC (g/dl) | 33.42 | 32.1-35.5 |

| TWBC x109 | 3.2 | 2-10 |

| Neut x109 | 1.76 | 0.8-4.5 |

| Lymph x109 | 1.44 | 0.4-6.5 |

| Mon x109 | // | 0.1-0.7 |

| Eos x109 | // | 0-7 |

| Bas x109 | // | 0-2 |

| Neutr % | 55 | |

| Lymph % | 45 | |

| Mon % | // | |

| Eos % | // | |

| Bas % | // | |

| PLT x109 | 455 | 96-776 |

A conscious blood sample was collected four weeks after the surgery and analysis confirmed that TBil, biochemistry and haematology values were now within reference ranges (Table 2).

The ferret was last seen six weeks after the second postoperative check-up with few episodes of vomit and soft stools resolved with a short course of oral ranitidine at 2mg/kg every 12 hours for 6 days.

The patient was then seen for the final time eight months after surgery and at this time was clinically normal. No hepatic or gastrointestinal signs, no abnormalities on examination, and stable weight and body condition were noted. Over the next year, further email updates were received with no further concerns reported.

Hepatic problems are quite common in ferrets – even if difficult to diagnose due to the typical subclinical status (Burgess, 2007). The most common hepatic diseases reported are lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis, bacterial hepatitis, biliary stasis, hepatic steatosis and neoplasms (lymphoma, adenocarcinoma and metastasis; Burgess, 2007).

The complete diagnosis needs the combination of several tests including full haematology and biochemistry, imaging (ultrasonography, CT) and ultrasound-guided, laparoscopic or surgical biopsy of the liver (Burgess, 2007; Hoefer, 2021).

The cause of biliary problems, such as cholelithiasis or “biliary sludge”, are not very well understood, even in domestic species, though ascending infection, pancreatitis, neoplasia and diet have been suggested as initiating factors (Otte et al, 2017; Neer, 1992). In this case, none of the aforementioned were identified as a contributing factor.

EHBO is an uncommon condition described in dogs, cats and several other species (Peek and Divers, 2000; Cousquer and Patterson-Kane, 2006; Coombs et al, 2002; Harwood et al, 2008; Pizzi et al, 2011). In ferrets, only recently has EHBO been reported (Hauptman et al, 2011; Huynh et al, 2014; Di Girolamo and Selleri, 2016) as a fairly common cause of “liver complex diseases”.

The indication for medical versus surgical management is not still well defined, but elevation of TBil and liver enzymes with radiographic and ultrasonographic evidence of biliary duct obstructions is often sufficient to justify exploratory laparotomy and treatment of biliary problems (Radlinsky and Fossum, 2019).

Untreated EHBO can cause chronic liver malfunction, secondary ascending gall bladder and liver infections, gallbladder or bile duct rupture and consequent bile peritonitis (Huynh et al, 2014).

The biochemistry confirmed the liver dysfunction and the abdominal ultrasonography confirmed the involvement of the biliary tract suspected based on the evident jaundice. A contrast CT scan would have provided greater detail on the appearance of the bile ducts and of the surrounding organs prior to surgery.

After surgery, serial blood analysis – particularly of liver enzymes and TBil – would have helped evaluate the patient’s recovery more precisely and serial ultrasonographic examinations would have allowed better monitoring of return to normal status of the biliary ducts within the liver.

The pre-anaesthetic protocol chosen was selected to reduce the possibility of smooth muscle and gastroenteric sphincter contraction that is caused by pure µ-agonist drugs such as morphine or methadone, even though these provide better analgesia.

Butorphanol was chosen despite the poor overall visceral and general analgesia to work synergistically to increase the analgesia effect of the pre-anaesthesia combination of medetomidine and ketamine that were used for their action of α2 and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (Clarke et al, 2014).

As pre-surgical supplemental analgesia, a “splash block” lidocaine was used, and the results were considered very good, with a smooth and uneventful anaesthesia and recovery, and no evidence of post-surgical discomfort observed within the hospital.

The use of a abdominal wall retractor greatly helped for the visualisation of the surgical area avoiding the body wall disturbing access to the surgical field.

Surgical magnifying loupes may have aided assessment and surgery further.

However, the advantages of a magnified surgical field have to be balanced with the discomfort caused by the limited depth of field provided and the difficulty to change visual focus to retrieve instruments, inspecting surrounding tissues and the training of the surgeon in the use of them (World Precision Instruments, 2015).

The surgical procedure has been successful, and the patient recovered very well; however, unfortunately the cause of the episode of lethargy and anorexia noted two days post-surgery was not able to be identified.

Ultrasonography and blood screening at this time would have helped to identify possible partial bile duct occlusion or local peritonitis, but were not possible. Fortunately, the episode resolved on its own within a few hours from the presentation.

Ursodeoxycholic acid treatment was started for its action as hepatocyte protection and to facilitate the bile flow, but would not have been expected to have been effective this rapidly (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2004).

The prognosis of cholecystectomy in dogs in the immediate postoperative period is guarded as fatalities can reach 40% (Smalle et al, 2015). However, the prognosis is excellent if the patients survive this immediate risk period.