12 Aug 2019

Hany Elsheikha summarises the latest thinking on preventive health care, and discusses the importance of owners adhering to control programmes to ensure they are successful.

Adult Toxocara canis, the most common intestinal roundworm of dogs.

Significant progress has been made in the field of companion animal parasitology, including the development of effective treatment and preventive anthelmintic drugs. However, helminth (worm) infections continue to adversely affect the health and welfare of companion animals and humans.

Part of the challenge is because parasitic helminths are well-adapted to infect and live inside a wide range of host species, and can even cross the species barrier – leading to serious accidental infection in unrelated hosts.

The broad geographical range, ubiquitous distribution and complex life cycles of helminths – together with increased domestic and international travel of pets and humans – are additional factors that facilitate helminths’ persistence in the environment and increase the opportunities for transmission of infection.

Protection of companion animals from infection with such stubborn parasites requires the adoption of new models of parasite control. Key to the success of any parasite control intervention is the ability to engage all stakeholders in clinical practice, academia and pharma in the development and implementation of best practices in parasite infection control. This multidisciplinary collaboration should be based on what each stakeholder can contribute, and should allow him or her to share resources and build on each other’s capabilities.

In this article, the author highlights some points of consideration towards the development of effective strategies for companion animal deworming.

The role played by animal health professionals in small animal practice is vital to protecting the health and safety of both companion animals and humans.

However, the veterinary profession faces a host of challenges – most notably the management of parasitic infections. Despite significant advances in the detection, treatment and prevention of helminth infection over the past two decades, helminth-related illnesses remain persistently high.

The burden of helminth/worm infection can be considerable due to adverse effects on animal health and welfare, and the associated economic implications. Additionally, some helminth infections can have the highest adverse impact on the elderly, children and people suffering from conditions that weaken the immune system, such as HIV infection, diabetes and cancer.

The detection of the larvae of the canine roundworm Toxocara canis in the brain of a young child, together with granulomatous lesions in the liver (Hill et al, 1985), demonstrates how parasitic infection in vulnerable individuals can lead to serious health consequences.

Given the significant impact of helminth infection on animals and humans, parasite control should be considered from a preventive perspective, and tailored to animals and individuals at particularly high risk for infection.

This article provides a unique perspective on the implementation of parasite treatment and prevention intervention programmes. Consideration is given to four key areas that influence the successful implementation of any control programme:

Also highlighted are key factors that underscore the challenges of the implementation of an effective parasite control programme.

Several factors can influence the risk of parasitic infection – and these can vary from one country to another.

Conventionally, pets travelling to certain endemic regions in Europe have always been considered at risk of acquiring the fox tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis, the causative agent of alveolar echinococcosis. Because this disease is considered one of the most serious parasitic zoonotic diseases in the northern hemisphere – and the risk it imposes remains eminent – all efforts must be made to prevent its introduction and establishment.

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the growing risk caused by the adoption of rescue dogs from abroad. It is normal nowadays to hear about dogs found on the streets in certain countries being brought to the UK by an animal welfare charity.

Lack of clarity about the clinical and treatment history of these adopted “trojan” dogs is a frequent cause for concern about the introduction of potential exotic parasites, such as E multilocularis, the filarial heartworm Dirofilaria immitis, the eyeworm Thelazia callipaeda and the tongueworm Linguatula serrata.

The smuggling of vulnerable puppies from abroad, particularly from eastern European countries, is another problem that has caught the attention of the profession in recent years. Investigations by Dogs Trust have revealed awful welfare concerns and serious health implications that smuggled puppies can experience (Woodmansey, 2018), with part of the problem attributed to the changes in the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) rules that were introduced in 2012, which allow puppies to enter the UK at a younger age. Dogs Trust sees Brexit as a crucial opportunity for the Government to put firm measures in place to protect dogs and the public.

Because parasites do not stop at geographical boundaries, it is important to internationalise our philosophy and approach for parasitic disease control. For example, imported pets should undergo proper screening for potential parasitic infections. Additionally, non-profit organisations – such as the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites UK and Ireland – and commercial businesses, such as the pet travel disease risk round table (Bourne et al, 2019), have been proactive in raising awareness of the potential risks associated with pet travel and illegal importation of pets from abroad.

Treatment and control programmes tackling helminth infections in companion animals require sensitive, reliable and accurate diagnostic tools.

Accurate and timely parasite identification can provide significant support to clinicians, especially when the results are needed to guide treatment or decide how often the animal should be dewormed.

Fortunately, the diagnostic tests available for the detection of worm infection have a good level of sensitivity and specificity. Faecal examination using the McMaster technique can not only detect the worm eggs/ova, but can also provide a quantitative assessment of the burden of infection. Isolation of lungworm larvae using Baermann’s technique has been widely used for diagnostic purposes.

In certain situations, the combined use of both the microscopic faecal detection method and antibody or antigen assay can provide more useful information than using a single method (Elsheikha et al, 2014; Schnyder et al, 2014).

Unfortunately, diagnosis of some worms – such as tapeworms – can be challenging. Detection of tapeworms is usually made by finding segments – also known as proglottids – on the animal’s perineum, or in the animal faeces or bedding. However, some tapeworms – such as Taenia species – cannot be easily distinguished based on the shape of their proglottids. Also, Echinococcus proglottids are only a few millimetres in length and can be easily missed.

The development and implementation of a risk-based approach for developing safe and rational use of antiparasitics in general – and anthelmintics in particular – has attracted the attention of parasitologists and veterinary surgeons in recent years.

Since the introduction of this risk-based concept to parasite control, the debate has been ongoing – with questions concerning the best treatment frequency that should be used for controlling roundworms and lungworms, and the benefits of using one anthelmintic over others.

However, limited attention has been given to analysing sources of uncertainty; therefore, a clear consensus is still missing.

The extent to which owners administer anthelmintic drugs to their pets – as prescribed by veterinary professionals – is known as compliance, which represents an important aspect of treatment success, better protection and good value for treatment costs.

Poor compliance is not only limited to medications; it can also take other forms, such as missing appointments, failure to adopt the recommended lifestyle changes, or failure to follow certain aspects of the recommended treatment programme (for example, prophylactic treatment before travelling abroad, or screening of imported dogs).

Therefore, the effects of poor compliance can extend far beyond mere financial implications, and increase the risk of infection to other pets and vulnerable individuals in the household.

Pet owners should be made aware of the fact the cost of treatment and/or other adverse health consequences can be substantially high if the treatment regimen or preventive measures have not been followed. It is often less expensive to prevent a disease/infection than treat it.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis can be highly effective if well implemented and pet owner adherence to prophylactic treatment is strongly associated with his or her understanding of the complications that may arise from not following treatment instructions. Therefore, it is important pet owners have a clear understanding of the treatment/prophylactic regimen requirements.

Answers to frequently asked questions should be provided as printed materials, whereas education about how drug works – and the critical relationship between compliance with the recommended dosing regimen and efficacy – should be emphasised to each client.

Additionally, periodic assessment for newly acquired misinformation or misunderstandings – through friendly, non-judgemental discussion of compliance difficulties – can be useful.

The impact of poor compliance is not trivial – even the best treatment could fail if the owner does not follow the instructions for administration of the antiparasitic drugs as prescribed.

Poor owner compliance can occur due to the difficulty in convincing pet owners of the need for preventive medications when parasites are perceived to be less prevalent in a pet’s environment. Many other factors can also influence compliance; these have been discussed in previous articles (Elsheikha, 2016a; 2016b).

Veterinarians need to have knowledge of these factors and understand the full dimension of the situation – only then they can effectively tackle the limiting factors to achieve better pet owner compliance.

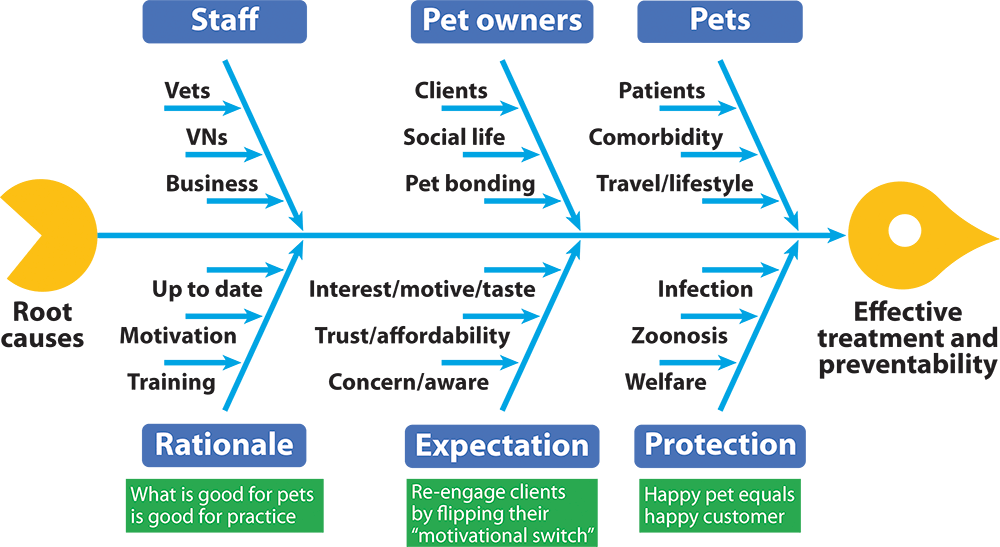

Fishbone analysis can be used to identify the causes of poor compliance, and all other factors that can influence the development and implementation of an effective programme for treatment and prevention of parasitic infections (Figure 1). On completion of this analysis, some solutions to the problem of poor compliance will likely be identified, including an action plan that can help practices make changes to their service to benefit both clients and staff.

Also, given the many challenges facing practising veterinarians, it will be critical to engage nurses and all members of the practice in team approaches to the provision of programmes tailored for education, counselling and compliance support of pet owners. It is important to continuously provide veterinary practice staff with training and professional development opportunities to equip them with the skills necessary to carry out these tasks successfully.

Promotional materials can educate pet owners about the risks of leaving pets unprotected and the benefits of applying prophylactic measures. The best methods for advising clients to be more compliant include sending mail/emails and text message reminders. In cases where compliance is poor, but treatment is of great importance, following up cases with a telephone call can be very effective in increasing pet owner compliance. Providing incentives to clients – such as discounts, free health checks and acknowledgements – are examples of approaches that should be used for improving compliance.

Additionally, implementing a patient-centred policy and supportive attitude can improve compliance (Elsheikha, 2016a; 2016b).

Owners with poor adherence history may require more adherence counselling to develop the consistent adherence necessary to successfully administer antiparasitic drugs to their pets as prescribed.

The author declares no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.