9 Oct 2017

Ian Wright, in the second of a two-part article, looks at the rapidly evolving danger of <em>Echinococcus multilocularis</em> establishing in the UK.

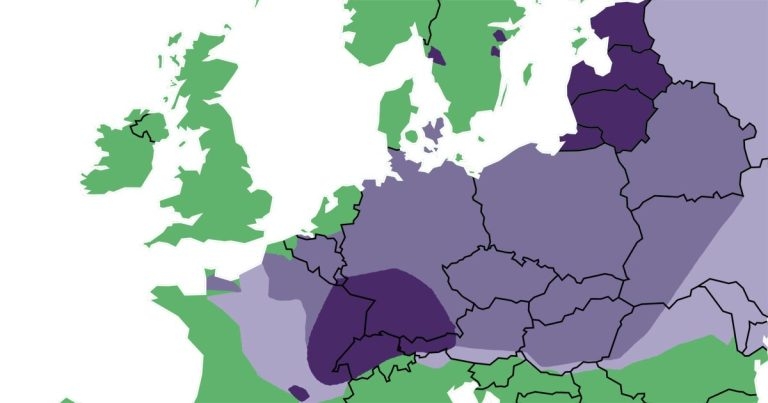

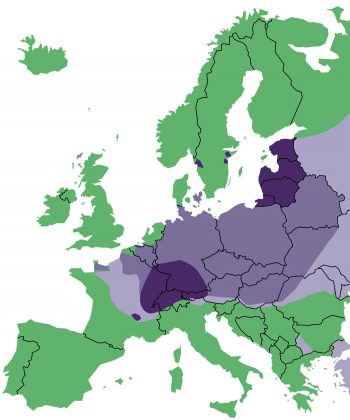

IMAGE: Redrawn from European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites. MAP: Fotolia/pyty.

Following on from the first part of this article, which discussed tapeworms endemic in the UK (VT47.34), this second part will consider the distribution of Echinococcus multilocularis in Europe and the threat of introduction of this parasite into the UK via pet travel and animal importation.

Eggs passed in the faeces of canids are ingested by a rodent intermediate host. The parasite then develops primarily in the liver, forming a cyst. Similar to E granulosus, these cysts have an inner germinal epithelium, from which brood capsules containing infective scolices bud off.

Unlike E granulosus, however, the cyst formed in the intermediate host is multilocular (also known as alveolar), containing many sub-compartments. This leads to greatly increased pathogenesis in the intermediate host as growth of the cyst is both locally invasive and capable of distant metastases in a similar way to a malignant tumour.

When cysts are ingested by canids feeding on prey animals, the scolices mature to adult tapeworms in the intestine. The adult tapeworms have a classic taeniid head with a scolex, but are only 6mm to 8mm long, with four to five segments (Figure 1).

Eggs are immediately infective once passed and human infection occurs through ingestion of these eggs, either directly from faeces or through contamination of the environment. E multilocularis is maintained in endemic areas by a sylvatic life cycle, with foxes and microtine voles in Europe being the main reservoir hosts.

E multilocularis infection is a severe zoonosis, with local and metastatic spread of cysts leading to hepatopathy and potential multiple organ involvement (Figure 2). Despite significant advances in treatment over the past two decades, infected individuals can still expect a significant reduction in life expectancy.

In the 1980s, human alveolar echinococcosis was vanishing from Europe due to improved food hygiene, decreased occupational risk of exposure and a decimated fox population following a number of rabies epidemics. Control of rabies in western and central Europe, however, reversed this trend as the fox population rapidly increased and expanded into urban areas.

In the year 2000, 559 cases of alveolar echinococcosis caused by E multilocularis were recorded in Europe. The past decade has seen a doubling of disease incidence in France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland; a dramatic increase in the Baltic States; and the disease becoming established in the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, Sweden and the north-western coast of France (Figure 3).

As well as urbanisation of the red fox, it is also thought increased immune suppression in the human population – due to increasing useof radiotherapy, corticosteroids and HIV infection – may also be playing a role in increased human infection.

Now, only the UK, Ireland, Malta, Finland and Iceland have endemic-free status in Europe.

The Pet Travel Scheme still requires dogs to be treated with praziquantel between one and five days before entering the UK. This simple treatment has prevented endemic foci from developing and remains vital. It has been demonstrated if this compulsory treatment is abandoned, it is almost inevitable E multilocularis will be introduced to the UK.

For every 10,000 dogs travelling on a short visit to an endemic country, such as Germany, the probability of at least 1 returning with the parasite is approximately 98%. This probability increases to more than 99% if dogs have been longer-term residents (Torgerson and Craig, 2009). Although the compulsory tapeworm treatment has provided protection against this, the half-life of praziquantel is 12 hours, allowing a window of opportunity of infection.

Three possible routes by which the parasite might gain entry to the UK were identified and discussed at the Veterinary Public Health Association (VPHA) and Association of Government Veterinarians spring conference (Figure 4 and 5) as of particular concern.

Although the compulsory treatment of dogs entering the UK has remained effective to date, the window of infection the one to five-day treatment period provides is of concern, given the large number of UK dogs travelling on the scheme.

More than 164,800 dogs travelled on the scheme from the UK in 2015 alone, and numbers have increased year on year since the scheme’s inception.

Robert Quest from the City of London animal health and welfare services discussed the control issues involved in protecting the UK from the importation of E multilocularis.

Compulsory praziquantel treatment on the pet passport scheme is vital for legally imported dogs to prevent entry of infection by this route, but a large number of dogs are also imported illegally without any preventive measures the scheme affords.

Vigilance from veterinary professionals and trade officials is essential to identify dogs travelling with incorrect or fraudulent documentation. The BVA reported one in three vets who treated pets had seen puppies they believed to have been illegally imported from overseas in 2016, and this is likely to be a significant underestimate of actual numbers of illegally imported dogs passing though veterinary surgeries.

Sian Mitchell of the APHA spoke about the surveillance for E multilocularis in animals imported, with a view to species relocation, zoos and breeding programmes. Many exotic mammals may act as intermediate hosts – a recent example being a group of beavers introduced into the wild in south-west England and subsequently found to be infected.

While it was acknowledged the risk of introduction of the parasite by this route was low, the beaver example demonstrates this is not just a theoretical risk and potential intermediate hosts imported into the country should be tested for the parasite (for example, ultrasonography for cysts) – particularly if intended for release into the wild.

If E multilocularis is allowed entry into the UK, the large fox and microtine vole population will make prevention of E multilocularis becoming endemic difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. In addition, it may take infected human individuals 15 years to develop clinical signs, making it likely infection would be well established in UK wildlife before human clinical cases became apparent.

Peter Chiodini, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Hospital for Tropical Diseases, acknowledged human cases of alveolar echinococcosis caused by E multilocularis in the UK were already a regular occurrence, all in people who had travelled abroad, or, more commonly, in immigrants from Europe who were infected before arrival in the UK. These cases were likely to be initially missed as UK general practitioners would be unfamiliar with the disease.

Stopping entry of E multilocularis into the country is vital to prevent establishment of the parasite and the morbidity that would follow from zoonotic cases arising from an indefinite period of endemic establishment in the UK.

Diagnostic options for individual veterinary practitioners to identify E multilocularis infection in travelled dogs are limited as faecal flotation for E multilocularis eggs carries a poor sensitivity. Coproantigen ELISA and PCR tests have been developed to try to provide more sensitive faecal diagnostic techniques.

Deplazes and Eckart (1996) found ELISA testing to be 80% sensitive, but this reached 93% in foxes, with worm burdens more than 55 in number. Specificity was 95% to 99%. PCR testing of faeces has proved very promising with a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 100% being reported (Dinkel et al, 2011). These tests are useful for large-scale screening, but are prohibitively expensive for testing of individual dogs.

Preventive treatment, therefore, remains the mainstay of E multilocularis control. It was agreed dogs should be the focus of attention in highlighting the need for preventive treatment. Cats infected with E multilocularis have a lower worm burden with lower fecundity than canids.

Eggs produced have also been demonstrated as more likely to be non-infective in experimental infections. Domestic cats, however, often have a close human bond and outdoor cats frequently predate. For these reasons, treatment of cats travelling abroad to endemic countries should still be advised.

If the establishment of E multilocularis as an endemic parasite in the UK is to be prevented then the following measures need to be promoted and employed.

Use of distribution maps, such as those on the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) website, and highlighting outbreaks in countries where the parasite is not endemic is vital when giving travel advice and assessing illegally imported dogs that have spent time in the UK before being identified. ESCCAP has a vital role in keeping these resources up to date as the distribution of this parasite is expanding rapidly into new areas.

Any legislation to prevent entry of parasitic disease into the UK is more likely to be effective if the pet-owning public understands its importance – and, therefore, are cooperative and compliant.

Owners who understand infected dogs represent an immediate zoonotic risk to them, as well as increasing the risk of the parasite establishing in the UK, are much more likely to be compliant than those who see the treatment as a purely bureaucratic exercise.

Advising treatment with praziquantel every 30 days pet dogs are abroad will prevent patent infection while the dogs are away and help keep owners safe from infection.

Advising further praziquantel treatment within 30 days after returning to the UK will prevent egg shedding if dogs have become infected with E multilocularis in the potential five-day window between compulsory treatment and return to the UK.

Advising owners to avoid their cats and dogs from predating or scavenging while abroad, if practical to do so, will try to prevent consumption of infected intermediate hosts.

Increasing vigilance for illegally imported dogs requires cooperation between vet professionals and Government departments to identify dogs too young to be imported legally or with fraudulent paperwork. Increasing the minimum age of travel and importation to six months would make identification of dogs below legal age easier, and also reduce illegal importations, as the highest demand is for puppies.

Test wildlife and zoo animals imported into the UK that may be potential hosts – particularly those intended for release into the wild.

E multilocularis is considered one of the world’s most lethal zoonoses (Craig, 2003), remaining on the World Health Organization‘s top 17 neglected tropical diseases. It is spreading across Europe and, although the UK is free of infection, is unlikely to remain the case if compulsory treatment with praziquantel for dogs before entry into the UK is dropped.

Maintaining this provision remains vital, but is not enough alone to minimise the zoonotic risk this parasite poses. Increased education, surveillance and cooperation between medical groups, the vet profession, the Government and parasite control groups, such as ESCCAP UK and Ireland and the VPHA, is vital if the UK is to remain free of endemic E multilocularis infection.