28 Aug 2017

In the first of a two-part article, Ian Wright looks at established and emerging tapeworms causing zoonotic and financial risk.

Vet and Veterinary Public Health Association council member Mike Jessop’s pre-conference briefing.

On 17 and 18 March 2017, the Veterinary Public Health Association – in conjunction with the Association of Government Veterinarians – held its spring conference in Cambridge. In a major departure from the traditional format of this meeting, covering a wide range of public health topics, this focused purely on tapeworms and a review of their control, titled “Controlling tapeworms: established and emerging”. It was well attended and generously sponsored by Bayer Animal Health. Three of the main themes to emerge from the conference were the large economic losses still being sustained by farmers through meat and offal condemnation, the re-emerging risk of hydatid disease, and the rapidly evolving risk of Echinococcus multilocularis becoming endemic in the UK.

This article considers the canine tapeworms causing zoonotic risk and economic loss in the UK, and the role of veterinary professionals in a “one health” approach in their control. The second part of this article will consider the separate problem of E multilocularis in relation to pet travel, dog importation and the risk of this tapeworm establishing in the UK.

On 17 and 18 March 2017, the Veterinary Public Health Association (VPHA) and the Association of Government Veterinarians held their spring conference, titled “Controlling tapeworms: established and emerging”. This was sponsored by Bayer Animal Health and aimed to consider the economic and zoonotic threats posed by canine tapeworm infections.

In the spirit of the “one health” agenda, various organisations across both the veterinary and public health professions were represented, and included:

UK CVO Nigel Gibbens and Scottish CVO Sheila Voas were also present.

The Friday programme was based around a series of short summary presentations by key sectors, which set in train a lively discussion drawing on the experiences of a well-informed audience.

The remit was to review the levels of knowledge about the management of these parasites, as well as explore potential future threats and control measures.

This was followed by a series of lectures on the Saturday, discussing, in further detail, the economic and zoonotic problems presented by canine tapeworm infections.

This article will consider the tapeworms discussed that are endemic in the UK. Taenia species represent a considerable economic loss to farmers, while hydatid disease – caused by Echinococcus granulosus – is a re-emerging domestic zoonotic risk. Part two of this article will consider the threat from abroad in the form of Echinococcus multilocularis.

The adult tapeworm is found in the intestine, attached to the intestinal wall. Eggs, or proglottid segments containing eggs, are passed in faeces and ingested by the intermediate host. This leads to cyst formation in the tissues and it is these cysts that arethen infective (usually through scavengingor predation).

The details of the life cycle vary depending on the species of tapeworm involved.

Taenia adult tapeworms are large (up to 500cm) in length and dogs become infected by ingestion of tissue cysts in ruminants and rabbits. This occurs through scavenging, hunting or the feeding of unprocessed raw diets.

Canids harbour small adult E granulosus tapeworms (5mm to 6mm long). Ruminants, pigs and man may all act as intermediate hosts, with the formation of hydatid cysts. These can lead to offal condemnation in farm animals, but – more seriously – significant pathology in man, with cysts forming in the bone, liver, CNS and heart. Ingestion of the cysts by canids occurs mostly through scavenging of carcases or feeding of offal.

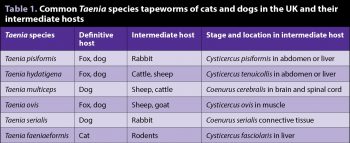

Canine Taenia tapeworms are found throughout the UK in lagomorph and livestock intermediate hosts, and are summarised in Table 1. With the exception of Taenia multiceps, which can lead to CNS signs in young ruminants (“gid”), infection is well tolerated in intermediate hosts and the greatest consequence of cyst formation is economic. This is because cysts will lead to meat and offal condemnation.

Food Standards Agency (FSA) data showed considerable economic loss from liver and carcase condemnation – with 742,000 ovine livers being condemned in 2012, costing £1 million (EBLEX, 2013); 548,000 livers condemned in 2015 (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board Beef and Lamb, 2016); and 66,500 lamb carcases rejected in 2012, at a cost of £5 million (EBLEX, 2013).

During the Friday discussions, it was suggested companion animal vets are largely unaware of these losses and education would be required to highlight these problems and their control. Taenia segments, however, are sometimes seen in the faeces of dogs whose lifestyles and diets put them at risk of infection. These proglottids are very visible to clients and reduce the human-animal bond due to owner revulsion, providing another important reason for their control in first opinion practice.

In a similar vein, it was suggested many companion animal vets consider hydatid disease to be a largely historical problem in the UK and limited to regional foci in Wales, the Welsh border, Herefordshire and the Western Isles of Scotland. Collin Willson, representing the FSA, gave a review of the state of hydatid disease in the UK.

Between 1974 and 1983, two cases of human hydatid disease occurred in Wales and 0.2 cases per million in the rest of the UK. A voluntary control programme of supervised praziquantel dosing of dogs in Wales reduced this incidence and was replaced by a health education programme in 1990.

In 2001, the foot-and-mouth outbreak proved a setback in hydatid disease control, as more carcases were easily available for dogs to scavenge. This led to an increase in prevalence of E granulosus in Welsh dogs from 3.4% in 1993 to 8.1% in 2002 (Buishi et al, 2005). Since then, the number of annual cases of human hydatid disease in the UK has remained fairly constant, with 12 cases in 2011 (Defra, 2012). The Welsh Government continues to raise public awareness of the disease and promotes praziquantel deworming programmes in dogs. This strategy, in place of more intensive control measures in the 1980s, has kept the incidence of disease low in Wales, but the low numbers of carcase rejections in Wales in 2006-7 led the FSA and the Welsh Government to consider the practice of many adult sheep being sold to other areas of Great Britain for slaughter may be inadvertently spreading the infection around the country.

Work carried out by the FSA on behalf of the Welsh Government found the incidence of E granulosus was much more widespread in England than previously thought. Postmortem inspections in abattoirs across Britain have produced positive cases, with a particularly high incidence on the Welsh border and north midlands. In 2015, data quoted at an FSA conference showed the incidence of hydatid cyst rejections in sheep and cattle offal to be 0.3% and 0.12%, respectively, across England and Wales.

While the possibility exists some of these condemnations may have been misidentified Taenia hydatigena cysts, these figures still present a significant risk that dogs will be exposed to infection through offal fed directly in hunts, kennels, farms and through unprocessed diets.

It is unknown to what extent canine infection is occurring and diagnosis in dogs is difficult due to faecal flotation being an insensitive method for taeniid ova detection (Wolfe et al, 2001). Even if E granulosus ova are seen, they are indistinguishable from the eggs of Taenia species.

Coproantigen ELISA and PCR tests have been developed to try to provide more sensitive faecal diagnostic techniques. Christofi et al (2002) found ELISA coproantigen testing to have a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 98%, dropping to 80% when T hydatigena infection was also present. PCR antigen testing faeces has also shown to be highly sensitive and specific (Abbasi et al, 2003).

Marisol Collins, from the University of Liverpool Institute of Infection and Global Health, has launched the The HyData Project to use these tools to establish prevalence of E granulosus in hunting dogs around the UK. This data will provide valuable insight into the extent to which E granulosus is established in dogs around the UK and, therefore, presenting a zoonotic risk.

Peter Chiodini, from the Hospital for Tropical Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, acknowledged human cases of hydatid disease in the UK were already a regular occurrence, mostly originating from abroad, but also of endemic origin.

These may well be initially missed, as general practitioners working outside of traditional endemic areas may be less confident about diagnosing hydatid disease.

Control of canine tapeworm infections is, therefore, vital to reduce economic impact, and reduce a severe and potentially increasing zoonotic risk.

Control measures require a “one health” approach, with veterinary professionals, parasitologists, meat inspectors and Government agencies all being required to play their part in bringing infection under control.

In traditionally endemic areas, dogs with any potential exposure to ruminant carcases, fed offal or unprocessed raw diets should be dewormed with praziquantel every six weeks. Outside of these areas, debate took place at the conference as to how frequently tapeworm treatment should be administered to at-risk dogs.

Examples exist of population groups in Wales and Asia where treatment of dogs every three months has reduced human hydatid disease over time (Craig, 2014), so this should be a minimum recommendation.

It is uncertain, however, to what extent deworming four times a year impacts on meat and offal condemnation rates, so, for this reason, dogs at high risk or those producing tapeworm segments should be dewormed monthly. This will eliminate proglottid shedding and minimise transmission risk to ruminants.

Prof Gibbens highlighted the fact appropriate anthelmintic treatment of farm dogs was a condition of farm assurance initiatives, such as the Red Tractor scheme, providing another means of ensuring good deworming compliance on farm.

The reliance of the profession of praziquantel and the risk of resistance developing was raised and, while it was agreed research to produce alternatives would be useful, praziquantel remains a robust treatment.

Similarly, raising farmer awareness in relation to clearing fallen carcases and not feeding raw offal to dogs may be beneficial – particularly in areas not traditionally endemic for hydatid, where awareness of the associated risks may not be as high.

While county councils heavily promote responsible disposal of dog faeces by owners, the importance of this in very rural areas and around livestock is less well-promoted.

The VPHA and ESCCAP UK and Ireland have important roles to play in supporting local councils in providing posters and literature to highlight the importance of this, in combination with regular deworming and keeping dogs on leads around livestock.

Ian Robinson, from the association of meat inspectors, highlighted the importance ofwell-trained meat inspectors in identifying cysts and accurately recording them, therefore breaking the tapeworm life cycle in ensuring it does not enter the food chain, and generating cyst prevalence and incidence data.

Raw diet feeding in dogs is increasing and, while unlikely to reverse in the short to medium term, it is vital raw meat and offal ingredients have been adequately inspected and frozen prior to incorporation into raw diets to minimise the risk of tapeworm transmission.

Despite praziquantel being highly efficacious in eliminating tapeworm infections in canines and effective meat inspection being in place across the UK, condemnation of meat and offal due to tapeworm cysts remains high, and hydatid disease continues to be endemic. The risk of E granulosus spread to dogs throughout the UK, via distribution of infected offal through abattoirs, is unquantified, presenting a zoonotic risk vets and doctors may not recognise.

Increased education, surveillance and cooperation between medical groups, the veterinary profession, Government and parasite control groups, such as ESCCAP UK and Ireland and the VPHA, is vital if the re-emerging problem of canine tapeworm infection is tobe controlled.