10 Dec 2018

Leila Bedos Senon outlines use of this diagnostic method and treatment options in patients with damage to the eye’s most outer layer.

Figure 3. A central corneal defect affecting the right axial cornea extending approximately 30% deep into the corneal stroma and corneal vascularisation. Findings are consistent with tear film quality abnormality. Image: University of Saskatchewan Western College of Veterinary Medicine ophthalmology department

Damage in the epithelial layer of the cornea – leading to exposure of the underlying corneal stroma – leads to a corneal ulcer3. Complicated corneal ulcer is a devastating ocular pathology that can lead to descemetocele formation or corneal perforation. Common aetiologies include either infectious or non-infectious. The non-infectious causes of corneal ulcers include:

Infectious causes are mostly associated with bacterial infections, viral and fungal infections3.

Regardless of the primary cause, secondary bacterial infections arise as the opportunistic bacteria from the conjunctival sac4. Most bacteria from canine ulcerative keratitis are Gram-positive, with Staphylococcus species constituting the major population followed by β-haemolytic streptococci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa; the latter two are typically isolated from canine malacic ulcer4.

In practice, corneal ulcers are commonly treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics before the results of bacterial culture and sensibility testing are available. When a patient with infectious keratitis presents, after detailed clinical examination, cytology samples with swab (standard or mini-tip) or specialised tools (for example, cytobrush) should be performed5.

Cytology examination should be performed before instillation of fluorescein or other topical substances. Cytobrush smears of the eye is a simple and inexpensive procedure, and useful in evaluating surface changes caused by diseases of the cornea, conjunctiva, eyelids and adnexa. However, the swab (Figure 1) is the least traumatic method to the eye for sample collection – especially for delicate areas such as deep corneal ulcers5.

When using a cytobrush, care must be taken to avoid ocular trauma and topical anaesthetic should be used before starting. After the sample is collected, it should be gently rolled, without rubbing, on to glass slides to minimise cell damage5.

The cytobrush (Figure 2) is an 8cm long plastic instrument with a tapered tip containing a nest of non-absorbent, soft nylon bristles (3mm to 4mm long). After collecting the sample, the slides need to be fixed quickly to prevent cellular degeneration (for example, heat from a hairdryer) and then stain (for example, Diff-Quik5).

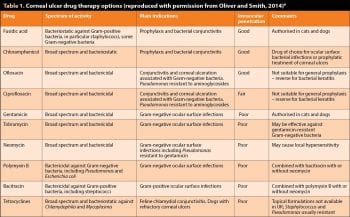

Therefore, it is valuable to be aware of the bacteria commonly involved in corneal ulceration and the likely antibiotic sensitivity. With this information, the vet can perform a cytological evaluation of the ulcerated cornea to start an appropriate antibiotic therapy before culture and sensitivity results are available depending on whether the bacteria detected are Gram-positive or Gram-negative rod or cocci (Table 1).

Moreover, ocular cytology can be very useful in determining if a patient is responding appropriately to therapy, or determining the necessity for additional diagnostic testing.

For successful management of ulcerative keratitis, the primary cause of the ulcer should be identified and removed. Superficial uncomplicated corneal ulcer can resolve with topical antibiotic therapy three to four times daily to prevent secondary bacterial infection1.

Combination ophthalmic preparations (such as neomycin, bacitracin and polymyxin B), erythromycin or oxytetracycline are good antimicrobial election. A mydriatic agent (1% atropine or tropicamide) is applied topically once or twice daily to control ciliary muscle spasm and the ocular discomfort associated with secondary uveitis1. Without a persistent underlying cause, a superficial ulcer should heal within two to six days1,3.

Corneal ulcers extending to the corneal stroma can be classified as progressive and non-progressive (Figure 3).

Non-progressive can generally be managed in the same way as superficial ulcers after culture and sensitivity results. This usually involves a secondary microbial infection. Surgical intervention is indicated in deep corneal ulceration; depth of corneal lesion is 50% of the corneal thickness.

In progressive deep stromal ulcers, antibiotic selection is made on the basis of cytology, culture and susceptibility test results. If the ulcer is becoming deeper or melting is present, aggressive topical antibiotic therapy every one to two hours is recommended with an antibiotic that covers Gram-negative rods (such as P aeruginosa) and Gram-positive cocci (such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species) while culture results are pending.

Good empiric choices would be late-generation fluoroquinolone (such as moxifloxacin) or a combination therapy with an early generation fluoroquinolone (such as ofloxacin) or aminoglycoside (such as tobramycin), in addition to a first-generation cephalosporin (such as cefazolin) or triple antibiotic are good empiric choices1 (Table 1). Topical anticollagenase-antiprotinase preparations are also recommended in most cases of progressive ulcerative keratitis1.

Only a few reports exist in veterinary medicine about the use of cytopathology in domestic animals7. Despite this, cytobrush is the most common technique to assess exfoliation of the ocular surface.

In one study, the use of impression cytology (IC) was compared to cytobrush. IC was found to be a simple, minimally invasive technique, and less time consuming than the cytobrush technique7. IC provides information about topography, cellular pattern, and the relationship between epithelial cells and other cellular components. However, the processing of the filter, including mounting the slides, requires more technical expertise.

The most important goals of corneal treatment are to preserve or improve the quality and quantity of light entering the eye in the presence of corneal opacities1. Cytologic specimens from bacterial keratitis are characterised by the presence of neutrophils and they are often degenerate8. The most common bacteria are Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Pseudomonas species8 (Figures 4 and 5).