18 Oct 2022

Hannah Van Velzen BSc, MSc, MRCVS discusses the significance of tackling this in cats and dogs – and how efforts can begin at home with owners.

Dental disease is possibly the most common, yet most underappreciated, disease found in companion animal practice, with some studies reporting more than 80% of dogs and cats above the age of three years old being affected1.

Periodontal disease is by far the most common diagnosis, but it is often missed or disregarded during routine clinical examination. However, its importance should not be underestimated.

Adequate identification and treatment of periodontal disease significantly increases quality of life, general health and longevity of our patients, and proper preventive care can even help stop it from developing in the first place.

Periodontal disease is not an infection in the classical sense, but is the result of a complex interplay between the bacteria present in the plaque biofilm and the host immune-inflammatory response. In patients without active oral disease, a steady state exists between the accumulation of plaque bacteria beneath the gingival margin and phagocytosis by neutrophils and monocytes.

These immune cells migrate into the gingival sulcus through the junctional epithelium located at the bottom of the sulcus, which seals the underlying periodontal ligament space from the outside world.

If plaque levels increase, for instance due to a lack of effective oral home care, this results in progressive increases in inflammation. This leads to multiple changes in the host response, including connective tissue infiltration by inflammatory cells, fibroblast apoptosis, lysosomal content and enzyme release by neutrophils, and collagen destruction.

In short, it is the inflammatory response that results in tissue destruction and attachment loss, not the bacteria alone. Left untreated, the disease will extend further into the periodontal ligament space and surrounding alveolar bone, resulting in pocket formation. These periodontal pockets allow for deeper penetration of bacteria, making it progressively difficult for the immune system to keep bacterial proliferation under control. This maintains the cycle of inflammation and tissue destruction2.

Although signs of oral discomfort in animals are easy for owners to miss, no doubt exists that oral inflammation and periodontitis in particular are painful conditions.

Dropping food or messy eating, moving food around the mouth while eating, favouring one side of the mouth, eating less, a new preference for softer foods, being less inclined to play with toys, wolfing food down without chewing, vomiting up un-chewed food soon after eating and salivation are common symptoms of oral pain that are often not clearly recognised by an owner until specifically asked about them.

This is because dogs and cats are extremely adaptable creatures, and will commonly learn to live with, and hide, signs of oral pain. Therefore, taking a thorough history is all the more important to confirm signs of oral discomfort (Figures 1 and 2).

Untreated periodontal disease ultimately leads to loss of teeth, but this can take a long time to occur. Particularly for multi-rooted teeth and those with large roots (such as canines and carnassials), significant destruction of bone and supporting structures needs to occur before teeth are lost.

The levels of local inflammation and bacterial invasion that remain present during this time can lead to infection of surrounding tissues, resulting in development of draining tracts, osteomyelitis, and/or significant cellulitis.

In the maxillary arches, chronic periodontal disease can lead to development of oro-nasal fistulae, where in the mandibular arches, pathological fractures may occur (particularly in small breed dogs). Chronic oral inflammation may also be a risk factor for oral neoplasia.

It is vitally important to recognise that the effect of oral disease is not limited to the oral cavity alone. The systemic effects of chronic oral inflammation have been thoroughly documented in humans and several links have been made in animals, as well.

These can include an increased risk for development of chronic kidney disease, thromboembolic disease and myocardial infarction.

Increases in blood urea nitrogen, creatinine and alanine transaminase have also been linked to untreated periodontal disease, as well as a bidirectional relationship with diabetes mellitus.

It is clear that adequate identification and prompt treatment of periodontal disease can improve the lives of our patients significantly, and the first step in doing this is recognising which patients are in need of treatment.

Although visual inspection of the teeth in a conscious animal is limited and can, therefore, not give us a definitive diagnosis, it can give us a general idea of whether periodontal disease is likely to be present, and whether further examination under general anaesthetic is warranted.

Common indicators of periodontal disease are summarised in Panel 1.

The full extent of periodontal disease can only be diagnosed under general anaesthetic, through a combination of a probing examination and imaging (most commonly dental radiography).

These two components of the examination complement each other and supply the clinician with different, but equally important, information to help determine the stage of periodontal disease (Panel 2). This in turn helps treatment options for each individual tooth to be determined.

During this part of the examination, a dental probe with measurement markings is inserted gently into the gingival sulcus at multiple points around each individual tooth to allow for depth measurement.

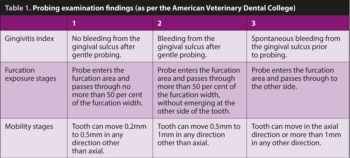

The gingival sulcus depth is generally considered to be less than 1mm in cats and 1mm to 3mm in dogs (depending on the size of the dog). Increased probing depths can be an indication of attachment loss, and their depth and location should be noted on a dental chart. Additionally, the probing examination allows for quantification of gingivitis, assessment of furcation exposure and assessment of tooth mobility. Depending on the finding, a specific “index” or “stage” (summarised in Table 1) is assigned to each finding, and this should also be recorded on the dental chart.

The probing examination is part of the visual oral examination, which, besides thorough examination of the teeth, also includes assessment of the occlusion and examination of the soft tissues of the oral cavity. All findings should be logged meticulously on a dental chart.

This not only provides clear communication to colleagues on specific findings, but acts as a clinical record of the oral health status on that day.

Many variations of dental charts exist and some are available to download for free3.

Dental radiography is an essential aid for diagnosis of a range of oral diseases – particularly periodontal disease. In recent years, it has rightfully become more commonplace in first opinion practice, allowing for provision of higher levels of care at a low additional cost.

Radiography complements the visual examination: clarifying findings of the probing examination and allowing the clinician to identify a significant amount of additional lesions that would otherwise be missed. Clinically important lesions in otherwise normal-looking mouths can be found in as many as 27.8% of dogs4 and 41.7% of cats5, which highlights the importance of its use in both species (Figure 3).

Not only can radiography help with treatment planning, it is also a useful tool for post-extraction control, allows for establishing a baseline for future monitoring, and acts as a strong visual aid for discussion with owners about pets’ oral health.

Defining the degree of periodontal disease present is the first step to determining which treatment options are available for an individual tooth.

The ultimate goals of treatment should be reducing bacterial load, eliminating associated inflammation, and halting progression of disease. A full set of dentition serves an important role in mastication, behavioural interactions and structural integrity of the skull.

Therefore, where possible, periodontal therapy can be considered in an attempt to salvage teeth rather than extract them. If a tooth is significantly diseased, and the owner cannot commit to ongoing home care or regular follow-ups under general anaesthetic, extraction may be a more appropriate option.

It is a common misconception that non-mobile teeth do not require extraction. However, it is not appropriate (author’s emphasis) to leave significantly diseased teeth in situ, even if they are not yet at a stage where mobility exists. Too often, such teeth are described in the clinical history as “solid” and no further treatment provided. It is important to recognise that without adequate care, these teeth will continue to be a source of inflammation, disease and pain.

Antimicrobial use in the face of periodontal disease does little to slow down progression of disease. Not only does it not address the inflammation that ultimately causes attachment loss, but it fails to even reach the bacteria that are inciting the inflammation as these are situated within a biofilm. This allows them to be extremely resistant to antimicrobials and topical disinfectants.

Vertical bone loss associated with stage two and stage three periodontal disease may be reversible if periodontal therapy is pursued.

Depending on the degree of bone loss present, this may consist of root planing (which can be performed in a first opinion setting), or of referral for gingival flap surgery, bone augmentation and/or guided tissue regeneration techniques.

The aims of periodontal therapy are three-fold:

The latter is absolutely essential for treatment success. As such, client communication and follow-up are key to successful periodontal therapy. If the owner cannot commit to ongoing home care or the patient is not of suitable temperament, periodontal therapy may still be successful if the patient is seen for regular professional cleaning under anaesthetic.

However, if this is also not possible, then prognosis for that tooth is poor and extraction may need to be considered instead.

If periodontal treatment is pursued, timely follow-up is important to determine whether treatment has been successful. Regular checks to guide and support the owner with home care are advised, and examination under general anaesthetic with repeat probing and radiographs should be performed after three to six months.

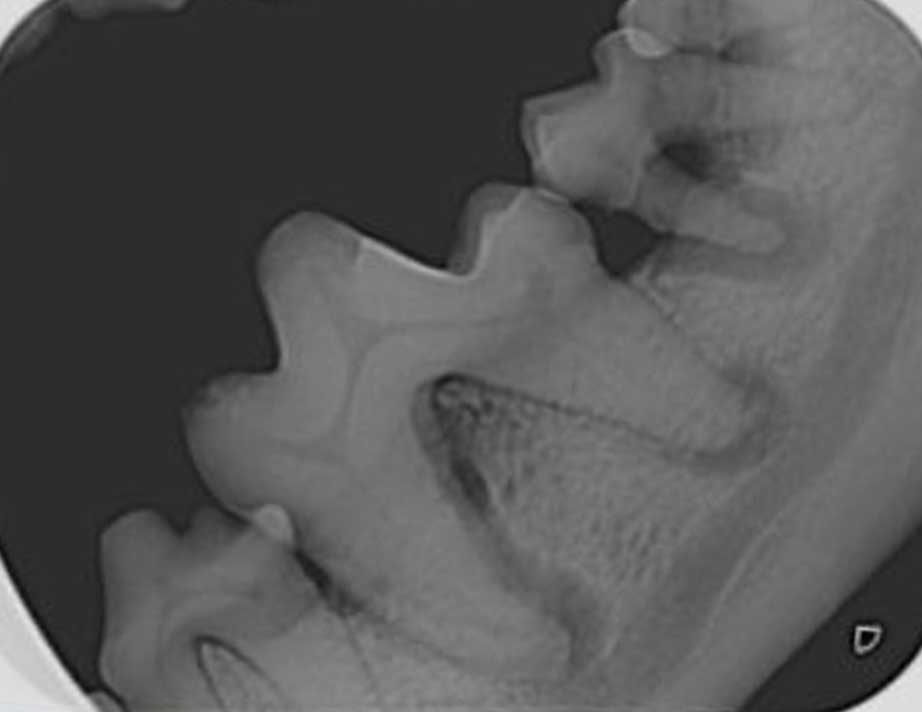

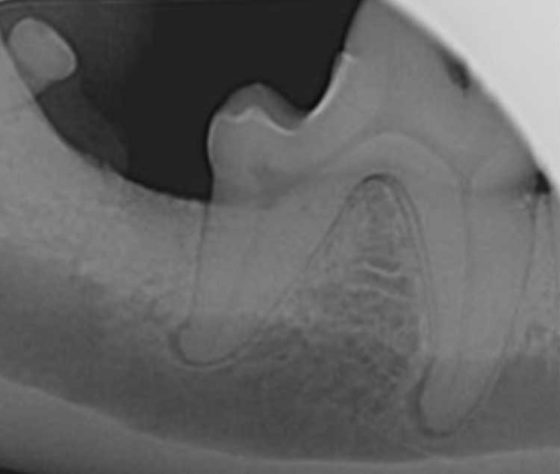

Figure 3. Dental radiograph of left mandibular first and second molar teeth in a mature dog with severe periodontal disease. Horizontal bone loss (overall loss of alveolar bone height) is present, as is vertical bone loss involving the mesial root of the first molar tooth and both roots of the second molar tooth. This explains the probing examination findings of increased probing depths in these regions, a stage three furcation exposure of the second molar tooth and a stage two furcation exposure of the first molar tooth. A periapical lesion of the distal root of the first molar tooth, which represents a perio-endo lesion, is an additional radiographic finding.

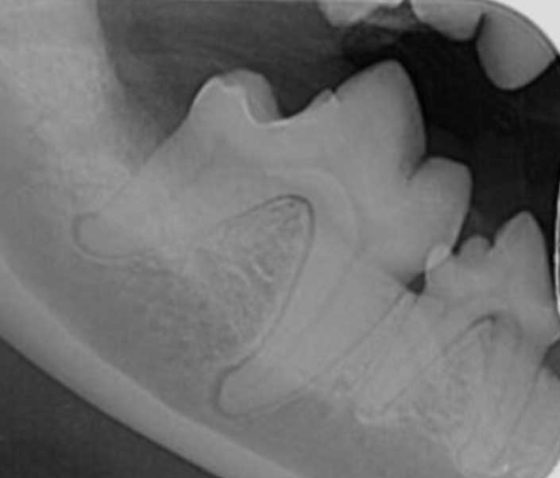

Figure 4. Dental radiographs of left and right mandibular first molar teeth in a five-year-old dog with moderate periodontal disease. The mandibular second molar teeth were extracted and open root planing performed on the distal aspect of the distal roots of the first molar teeth. The owner was very motivated to salvage the teeth and committed to twice-daily brushing.

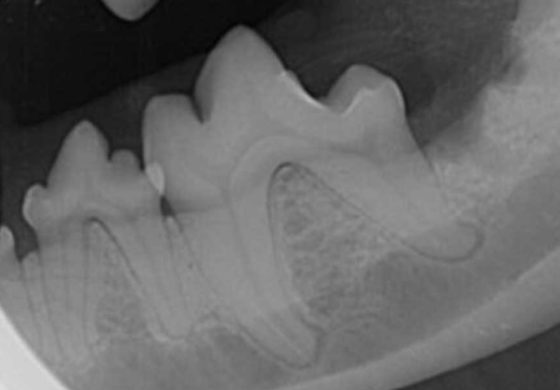

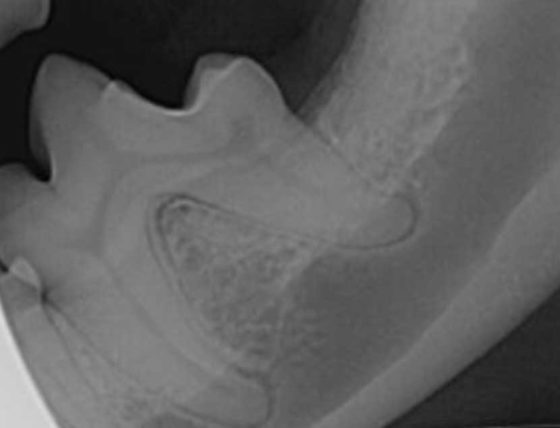

Figure 5. Repeat radiographs of the same patient as Figure 4, taken five months after periodontal therapy. The vertical bone defects have filled with new bone and periodontal ligament has redeveloped around the root, indicating successful treatment of periodontal disease. It should be noted a degree of horizontal bone loss is still evident, which is to be expected as alveolar bone height is known to be a more permanent change.

Root planing is a type of periodontal treatment that can easily be performed in a first opinion setting and is a viable treatment for most mild to moderate periodontal pockets (Figures 4 and 5).

The technique involves removing calculus embedded within the cementum while simultaneously creating a smooth root surface. It requires slightly more force than scaling, but also a degree of precision to prevent damage to the root surface.

Commonly used hand instruments for root planing are the universal and Gracey curettes, which unlike scalers have a rounded tip and are, therefore, suitable for insertion into the subgingival space without causing trauma to surrounding tissues.

The sharp edge of the curette is aligned with the root surface at a 45 degree to 90 degree angle, and sharply pulled in the direction of the crown to clean the root surface.

For periodontal pockets up to 5mm in depth, root planing can be performed non-surgically, but for those deeper than 5mm or teeth with other pathology (such as furcation exposure) an open technique with use of a surgical flap is indicated to allow full visualisation of the root surface (Figures 6 and 7).

Although treatment options exist for teeth with mild to moderate periodontal disease, the ideal message to clients from the start should be to prevent disease from occurring in the first place.

This can aid avoidance of the detrimental effects of periodontal disease on patient comfort and systemic health, and reduce the need for general anaesthetics and/or extractions. As discussed previously, the inciting factors of inflammation are the bacteria present in plaque biofilm, which are highly resistant to antimicrobials and topical disinfectants.

Mature plaque forms on dental surfaces within 24 to 48 hours and the single most effective way to prevent periodontal disease is mechanical removal of plaque through active brushing of the teeth. Communicating the importance of tooth brushing, teaching owners how to brush, and providing owners with regular checks and guidance are areas in which veterinary nurses, in particular, excel (Figures 8 and 9).

Dental diets, chews, and water and food additives are commercially available to help support dental care, but none are as effective as brushing, highlighting its importance as the gold standard of dental home care.

If the owner is unable to brush, but still wishes to provide some preventive care, these products can and should be implemented. However, they should then be combined with regular checks and professional cleaning under anaesthetic to maintain oral health. Teeth with irregular surfaces, such as those with pre-existing calculus build-up or tooth fractures, are more prone to plaque adherence and advice to owners should, therefore, include an initial professional cleaning under anaesthetic where appropriate, and avoidance of hard chews, such as bones, antlers and yak milk chews.