30 Jun 2020

Gary Campbell BSc, BVSc, MRCVS Mike Farrell BVetMed, CertVA, CertSAS, DipECVS, MRCVS describe the signs associated with this presentation, as well as the assessment of both conscious and sedated or anaesthetised dogs.

General practitioners and specialist orthopaedic surgeons are frequently presented with dogs whose owners report severe intermittent hindlimb lameness despite an apparently normal orthopaedic examination.

In many cases, screening radiographs show hip dysplasia – and it is tempting to attribute the clinical signs to this problem. This can lead to discussion about potentially invasive surgery, including triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO) and total hip replacement. Before considering such interventions, it is vital the attending clinician is certain of his or her diagnosis.

Clinically occult hip dysplasia is very common. In one clinical study of 406 dogs with a radiographic diagnosis of hip dysplasia, 185 dogs (46%) had not displayed any clinical signs at the time of diagnosis – the diagnosis of hip dysplasia was incidental (Farrell et al, 2007).

Even performance dogs can be affected by non-clinical hip dysplasia. In another study that assessed the impact of radiographic hip dysplasia on military working dogs (Banfield et al, 1996), the total number of months worked by 58 normal dogs was not different to the months worked by 58 dysplastic dogs (approximately 50 months each).

If we accept the premise that radiographic hip dysplasia is a common incidental finding, we need to increase our awareness of the important differential diagnoses.

Canine hip dysplasia can manifest as a clinical problem in dogs of any age, although clinical signs are unusual in dogs younger than five months of age.

Pain can be caused by hip subluxation (usually in immature dogs), secondary OA (usually in skeletally mature dogs), or both. Importantly, a visible limp is relatively uncommon and only tends to occur in young dogs with hip subluxation.

In skeletally mature dogs, intermittent limping is uncommon and clinicians should look for other sources of lameness, including cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) insufficiency and lumbosacral intervertebral disc disease (LSIVDD).

Vocalisation – such as yelping or howling in pain – are rare in dogs affected by any form of developmental or degenerative orthopaedic disease.

Signs of severe acute pain should increase suspicion for spinal pain/neuralgia (for example, LSIVDD).

In some dogs, CCL disease and patella luxation are easy to rule out based on an orthopaedic exam.

A positive cranial draw or tibial compression test is diagnostic for CCL insufficiency. However, in some cases, dogs are affected by partial CCL tears without any obvious cranial draw. This problem, sometimes termed “stable CCL disease”, can be difficult to definitively diagnose.

These tests can be useful:

Cruciate ligament disease is common in adult dogs showing lameness that was previously attributed to a radiographic diagnosis of hip dysplasia. In one study of 369 dogs, CCL disease was confirmed as the cause of hindlimb lameness in 32% of cases that were referred for signs attributed to hip dysplasia (Powers et al, 2005).

Although no supporting data exists, a widely accepted dogma suggests that in dogs with radiographic stifle pathology and concurrent radiographic hip dysplasia, treatment of the stifle problem will result in a good outcome despite the concurrent hip problem – hip dysplasia in these cases is frequently an incidental finding.

Thigh muscling can be assessed semi‑objectively by wrapping your fingers around the thigh at its widest point (Figure 1), and comparing overlap of the fingers or the gap between the fingers, allowing a comparison between muscling on the left and right. This can be a useful way to establish which side is more affected in dogs with bilateral pathology.

A tape measure can be used to provide a more objective assessment. It is important to ensure the dog is standing square during this measurement.

Hip extension can be assessed passively by fully extending the hip joint (Figure 2) and recording range of motion, comparing left and right. Pain responses include withdrawal of the limb, vocalisation or trying to bite.

It is important to note that in fully extending the hip joint, it is not possible to isolate the hip as the source of pain. The lower back and stifle joints are also extended, so a positive response to passive hip extension can indicate the following sources of pain:

In dogs that resent a veterinary clinical exam, it can be difficult to interpret the response to passive hip extension. It is useful in these cases to question the owner about voluntary (active) hip extension at home.

If dogs are happy to jump up to greet the owners (Figure 3), climb stairs and lie in a prone position with the hips fully extended, it is less likely that the hips are causing pain in extension.

Early diagnosis of hip dysplasia has several potential advantages.

Affected dogs can be recognised early and excluded from the breeding pool, therefore effecting an improvement in population control over the long term.

Individual advantages also exist, as some procedures are only effective when applied to young dogs. Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis is only effective in dogs younger than five months of age and double pelvic osteotomy or TPO is typically only effective in immature dogs.

In the US and other parts of Europe, early diagnosis is made using versions of a passive radiographic laxity test called the distraction index test. As this test requires manual restraint, it is not allowed in the UK.

The most common test employed for early detection of laxity in the UK is the Ortolani test. This test is used to assess passive hip laxity and can be performed either with the dog in dorsal or lateral recumbency (Figure 4). The hip and stifle joints are flexed to approximately 90° and an axial force is applied proximally along the femur. If laxity is present, this will cause hip subluxation.

The femur is then gradually abducted while the axial force is maintained (Figure 5). The opposing hand is used to prevent the dog sliding across the table and the thumb of this hand is positioned over the hip to feel for a “clunk” when the hip reduces into place. The angle of abduction at the point that the clunk occurs is termed the “angle of reduction”.

This manoeuvre mimics what would happen in a TPO, but instead of rotating the acetabulum to increase coverage of the femoral head, the femoral head is rotated back into the acetabulum.

The maximum angle of rotation allowed by a TPO plate is 30° – so for a dog to be a good candidate for TPO, they must be Ortolani‑positive, with a defined “clunk” at the point of reduction, and an angle of reduction less than 30°. They also need to have no radiographic evidence of remodelling of the joint (Figure 6) and at least 50% femoral head coverage on the frog-leg ventrodorsal radiograph (Figure 7). This radiograph mimics the Ortolani test, which, in turn, mimics TPO.

A case report is detailed in Panel 1 at end of article.

Many of the clinical features of hip dysplasia and LSIVDD overlap. Affected dogs are usually from large or giant breeds and are frequently affected by exercise intolerance, stiffness after rising, and difficulty jumping and/or climbing stairs.

Most dogs are middle-aged or older, whereas hip dysplasia can affect dogs of any age. Signs including intermittent severe lameness, vocalising in pain and hindlimb weakness (including falling) are common in dogs affected by LSIVDD, but not in dogs with hip dysplasia. Many dogs with LSIVDD only show signs related to pain and do not demonstrate any other neurological deficits.

Several techniques can be used to help diagnose LSIVDD:

Suspicion should be increased if the dog is mature, large or giant breed and normally active. Very active dogs can be affected as young adults, in particular border collies that compete in agility. Suspicion is high in dogs that vocalise in pain or show neurological deficits, including foot scuffing, knuckling or urinary/faecal incontinence.

In cases where hip dysplasia, CCL disease and patella luxation have been ruled out clinically and radiographically, the top two differential diagnoses for chronic hindlimb lameness are LSIVDD and iliopsoas strain injuries.

Physical exams that isolate the lower back or sciatic nerve are helpful. These include deep palpation of the lumbosacral spine (Figure 11), the lordosis test (Figure 12) and deep palpation of the sciatic nerve between the hamstring muscle bellies (Figure 13).

MRI is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of LSIVDD. Unfortunately, like hip dysplasia, poor correlation exists between the MRI findings and clinical signs (Mayhew et al, 2002) so the findings must be interpreted with caution after considering other factors that localise pain to the lumbosacral intervertebral disk.

Treatment on suspicion can be performed using oral gabapentin or pregabalin. These medications have a good reputation for treating neuralgia, but not for treating orthopaedic pain. If response to treatment is good, this increases suspicion of LSIVDD. The same is true of epidural injection of methylprednisolone (Janssens et al, 2009), but, ideally, this procedure should only be performed after diagnosis has been confirmed with an MRI scan.

Most of the available information on iliopsoas muscle strain injury is anecdotal. Affected animals share a similar signalment and clinical signs to animals affected by LSIVDD, so some overlap with hip dysplasia also exists.

Affected dogs will usually show a severe pain response during deep palpation in the groin immediately cranial to the hip joint; however, deep palpation of the groin is potentially an uncomfortable manoeuvre, even in clinically normal dogs. Diagnosis is typically only confirmed after ruling out stifle and hip pathology, and confirming a normal lumbosacral intervertebral disc using MRI.

Changes in the iliopsoas muscle can be seen on MRI – particularly when gadolinium enhancement is used.

Canine hip dysplasia is a very common condition diagnosed in general practice, but it is possible its clinical relevance is at times overstated.

To ensure animals with occult hip dysplasia and concurrent orthopaedic abnormalities are correctly managed, a thorough physical examination and evaluation for possible differential diagnoses is essential.

Panel 1. Case report

A four-year-old, 35kg, mixed-breed dog presented with a one-and-a-half-year history of bilateral intermittent hindlimb lameness.

When the dog was one year old, a radiographic diagnosis had been made of bilateral hip dysplasia. Lameness was worse on the left and progressed over the preceding two to three months. Symptomatic treatment with prolonged rest and daily meloxicam improved lameness, but incompletely.

Gait examination revealed bilateral hindlimb lameness that was slightly worse on the left. A video clip supplied by the owners showed 10/10 left hindlimb lameness. The remaining examination was very challenging due to fear aggression.

An orthopaedic exam was performed under deep sedation. Hip range of motion was reduced bilaterally, but worse on the left. A suspicion of stifle joint effusion was made based on an indistinct abaxial border to the patella tendon bilaterally. Cranial draw was not present.

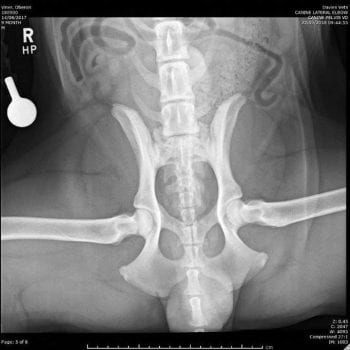

Radiographs were acquired of the hips and stifles (Figures 8 to 10). These showed bilateral stifle joint effusion (seen as effacement of the infrapatellar fat pad), bilateral hip dysplasia with secondary OA and a transitional lumbar vertebra.

Synovial fluid was aspirated from both stifles (1.5ml and 1ml of watery, straw-coloured fluid from the left and right stifles, respectively). The predominant cell type was mononuclear with less than 10 per cent neutrophils bilaterally.

Bilateral stifle arthroscopy was performed and bilateral partial CCL ruptures were confirmed. Staged bilateral tibial plateau-levelling osteotomies were performed, resulting in a full return to normal activity without lameness or any requirement for medications in the long-term.