6 Nov 2017

Holger Volk discusses various novel concepts and alternative options for managing this prevalent disease in canine patients.

Figure 1. Around 1 in 111 dogs will be diagnosed with epilepsy. IMAGE: Fotolia/Evgeniya M.

About 1 in 111 dogs that present in first opinion practice will be diagnosed with epilepsy (Figure 1). Most practitioners will feel confident about the concept of diagnosing idiopathic epilepsy by ruling out metabolic or structural diseases, as well as how to treat a standard dog by prescribing appropriate antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

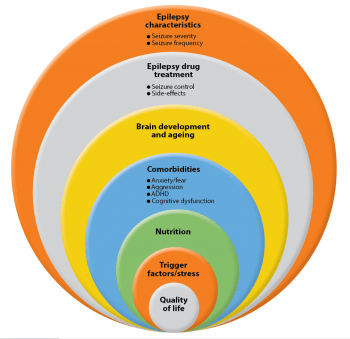

In part, this confidence was gained by the plethora of information being provided in lectures and veterinary publications – many of them being based on recommendations made by the International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force1-5. However, canine epilepsy is far more than a simple seizure disorder and new concepts are emerging that do require a rethink of how we manage this condition (Figure 2).

An article co-written by the author6 highlighted that dogs with epilepsy can also develop comorbidities, such as anxiety and ADHD, as well as have AED side effects, complications of AED treatment and early death – affecting, therefore, not only quality, but also quantity, of life. In addition, evidence has shown dogs affected by idiopathic epilepsy also have reduced trainability and suffer from cognitive impairment.

It is known, from research in people, that comorbidities and AED side effects can influence the quality of life more than seizures alone6. However, in veterinary medicine we continue to mainly focus our attention on treating seizures, ignoring other quality of life-reducing factors. Little is known, but we do know between 20% to 60% of dogs with idiopathic epilepsy are euthanised as a direct consequence of this brain disease and the side effects of AEDs7.

Epilepsy management strategies have mainly ignored the impact of comorbidities and AED side effects on the quality of life of dogs with idiopathic epilepsy, and also on the quality of life of their owners. This article will provide readers with some new concepts the author hopes will be useful for daily practice.

Most epileptic dogs will have a relatively stable seizure frequency, but a subpopulation of dogs with idiopathic epilepsy exists in which seizure severity and its frequency progresses with time8. The major risk factor for a progressive course of this brain disease is a high seizure density (cluster seizures) or severity (status epilepticus)9. A very high seizure density and prolonged seizure activity (status epilepticus) can potentially lead to brain damage, drug resistance and death.

These patients require early AED treatment. AEDs will always remain the backbone for epilepsy management and is especially required in animals with an increasing seizure frequency, a seizure frequency of two or more seizures per six months, cluster seizures and/or status epilepticus2.

The recommendation for starting dogs on epilepsy treatment – if they have two or more seizures in a six-month period – is mainly based on what owners feel comfortable with, but this is obviously a rule of thumb and needs to be tailored to the individual owner/dog combination.

A study followed a cohort of dogs with idiopathic epilepsy that received no treatment8. The individual seizure patterns were variable and no overall clear pattern was present. Some dogs had many seizures, then no seizure for a while, or vice versa, while some seizures were like clockwork, with similar interseizure intervals or the pattern appeared random.

Overall, the median time between the first and second seizure was around 70 days, and the time interval between the preceding seizures was always around 50 days. Further studies are needed to evaluate seizure patterns over time and look at the natural development of the disease process.

Epilepsy is a chronic disease and, as aforementioned, the majority of dogs with idiopathic epilepsy will be stable or “wax and wane” in seizure frequency. However, dogs with high seizure density, duration and severity are more likely to deteriorate and require early intervention9. Medication with AEDs poses a fine balance between benefits and potential side effects, such as polyphagia and weight gain, polydipsia, polyuria, hyperactivity, sedation and ataxia10,11.

Quality of life of the owners is especially impacted by sedation and ataxia10,12. On the other hand, the quality of life of the epileptic pet is perceived by the owner to be mainly impacted by a high seizure frequency and receiving polypharmacy (three or more AEDs)12. Poor drug response is frustrating for owner and vet alike. Seizures are seen by owners as “unpredictable” and “uncontrollable”, and cause a stress response (cortisol peak) in owners and pets13.

The ultimate aim for epilepsy management remains “seizure freedom” without causing quality of life-limiting side effects3. It appears seizure remission remains a difficult goal to achieve with AED medication alone.

Independent of the mechanism of action of the first AED used, each unsuccessfully used AED will reduce the chance of the next AED being successful, which suggests some unspecific mechanism for drug resistance, potentially independent of the disease itself and more a result of a stress response to a high seizure frequency or severity21.

Recent work has shown overall response rates (with response defined as greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency) to succeeding interventions are 37% (first), 11% (second) and 6% (third) AED, respectively22.

When AEDs are not the only answer, what can you do as a practitioner to help these patients? Reducing stress and other trigger factors appear, from anecdotal evidence, to help control seizures in some patients. As is the case for many chronic diseases, having a daily routine, controlling the environment by reducing potential trigger factors, ensuring a stable and high-quality diet, might help increase the individual’s seizure threshold and reduces the chance of further seizures.

An increasing level of evidence in people has shown the importance of nutrition for brain health and for brain diseases such as cognitive dysfunction and epilepsy. It has been known for a while in people that diet can improve epilepsy23. Anecdotally, many owners, breeders and canine epilepsy support groups commonly report the importance of diets and supplements for the control of canine epilepsy. However, only a few scientific studies have explored the role of nutrition in epilepsy management24.

It has been shown the salt content in the diet has to be consistent for dogs treated with the AED potassium bromide. The sodium chloride content of the diet affects the pharmacokinetic of potassium bromide, by changing clearance of bromide, with higher chloride contents reducing serum bromide levels2.

A study using omega-3 fatty acids dietary supplement showed no improvement in seizures25. Interestingly, a study from Glasgow showed, in a small population of dogs with drug-resistant idiopathic epilepsy and gastrointestinal hypersensitivity, seizure control improved when fed a hypoallergenic diet26.

Neurons have been shown to improve their function significantly when using ketone bodies (acetone, acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate) as energy supply instead of glucose. Improving brain metabolism has been one explanation why KDs could improve seizure control.

The original KD, characterised by its high fat and low carbohydrate content, has been used for many years successfully in children with drug-resistant epilepsy, even allowing reduction or cessation of AED in some patients28, 29. This diet is also effective in adults, but compliance is an issue. In dogs, the original high fat, low carbohydrate/protein KD was studied in a small cohort of dogs with idiopathic epilepsy, which showed no significant effect30. A more promising KD is based on medium-chain triglycerides (MCT), which significantly improved seizure control between groups27.

The MCT diet was tested in a six-month prospective, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover dietary trial in chronically AED-treated dogs with idiopathic epilepsy, which were difficult to control27. One in seven dogs stopped having seizures when the MCT KD was added to the medication and half the dogs had a 50% or greater reduction in seizure frequency.

Many of the enrolled dogs had cluster seizures, therefore the number of seizure days was also assessed, which also significantly decreased on MCT diet.

Dogs on MCT diet had a significant increase in the ketone body measured. MCTs are known to have a higher ketogenic yield. Interestingly, fatty acids with structures related to valproic acid – an AED used in people – have shown to have brain-suppressing effects31. Strong evidence now also exists that MCT-derived decanoic acid (capric acid) has direct anti-seizure effects, being a non-competitive α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist, in a voltage and subunit-dependent manner32. This is interesting, as it could complement most AEDs used in dogs with epilepsy that work on the gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic axis, increasing the function of the inhibitory brain pathways33, 34.

Interestingly, in the study describing decanoic acid having a direct seizure suppressing effect, the ketone bodies acetone or beta-hydroxybutyrate had no effect32. The main mechanism of action for MCT KD could, therefore, be speculated to be the blocking of the AMPA receptor. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been reported with intensive seizure activity. Decanoic acid can regulate mitochondrial proliferation and function35, which could be another potential mechanism of action.

As mentioned, dogs with epilepsy can also have behavioural changes. More than two-thirds with idiopathic epilepsy were affected in one study, of which most showed changes in anxiety/fear or defensive behaviour36.

Studies have also shown some dogs with epilepsy can develop ADHD-like signs. It is not known which drug might work best for the treatment of these behaviour changes. Treatment of behaviour changes could improve quality of life, but might also improve epilepsy control. An MCT-enriched diet improved chasing behaviour (a potential indicator of canine ADHD-like behaviour) and a reduction in stranger-directed fear, which may indicate anxiolytic properties of the MCT37.

Further research is needed on how nutrition and drug treatment can influence behaviour changes seen in dogs with epilepsy, and how and if this can improve quality of life and seizure control. Unpublished data from the lab where the author works also showed a decrease in cognitive function in dogs with epilepsy.

MCT diets have also shown to improve cognitive function in ageing dogs38 and, therefore, this could be another indication for MCT-enriched diets. MCTs occur naturally in a variety of sources, including milk. Human milk will vary its MCT content depending on the baby being pre-term (17%) or full term (11%). Commercially available MCTs are usually sourced from botanical oils, such as coconut oil (Figure 3) and palm kernel oil.

Last but not least, one of the most important factors for successful management of epilepsy is having good data, such as reliable seizure diaries (Figure 4), along with “education, education, education” for the owner.

Therefore, a good working relationship and communication between a veterinary practitioner and an owner is of pivotal importance, as the more the owner understands the disease, the more compliant he or she is.

Furthermore, only detailed questioning and open communication will give the veterinary practitioner important clues about the non-drug-related factors discussed in this article.

Idiopathic epilepsy is not one disease – it can be caused by a plethora of aetiologies and only means structural and metabolic reasons have been ruled out.

Epilepsy is a complex disease that will frequently not respond to a “one size fits all” management solution. Working together with the owner and having a “holistic” approach with AED as the backbone will provide the best chance of successful epilepsy management, helping improve quality of life of the patients and their owners.