27 Feb 2017

Parasitologist Ian Wright, head of ESCCAP UK & Ireland, discusses human toxocarosis, its control and the role of cats in its transmission.

Figure 1. Toxocara spp. adults.

Veterinary surgeon, co-owner of the Mount Veterinary Practice.

Independent Parasitologist and head of ESCCAP UK & Ireland.*

Toxocara spp. are a group of intestinal nematodes infecting dogs (T. canis) and cats (T. cati). They are the most common nematodes seen in small animal practice and there is some awareness of the zoonotic risk they pose among the public.

While the role of T. canis and environmental contamination through dog fouling is well recognised by veterinary professionals, government and the public, the role of T. cati in the epidemiology of human toxocarosis has been more overlooked; recently it has started to come to light as a likely significant contributor to this debilitating zoonosis.

This article discusses human toxocarosis, its control and the role of cats in its transmission.

Adult worms (Figure 1) lie in the small intestine and shed eggs into the environment via the faeces of the host.

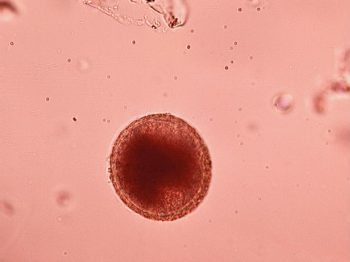

The eggs when first shed are unembryonated (Figure 2) and are not infective. Progression to the embryonated stage is required for infection, so fresh faeces do not present a zoonotic risk.

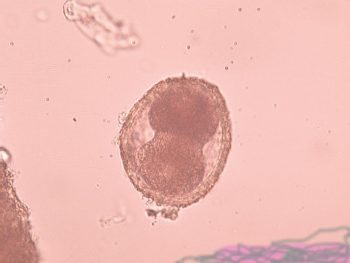

Nuclear division takes place within the ova (Figure 3) until embryonation takes place in two to seven weeks under optimum conditions.

Although cats may be infected by ingesting embryonated eggs, the most important routes of feline infection are trans-mammary infection and consuming paratenic hosts such as rodents. Trans-mammary infection ensures a high prevalence, approaching 100%, in kittens without anthelmintic intervention.

As cats age, they develop a degree of immunity to the parasite, which reduces the chances of worms producing eggs and, as a result, the prevalence of patent infection in adult pets is lower than in kittens but can vary considerably.

The prevalence of T. cati in cats in Western Europe has varied between 8% and 76% in recent studies (Overgaauw & Van Knapen 2013). Populations with lifestyles that increase their exposure to paratenic hosts, such as strays and hunting pets, can be expected to have a higher prevalence.

A recent study in the UK found untreated adult domestic cats with outdoor access to have a prevalence of patent T. cati infection of 26% (Wright et al. 2016), demonstrating that prevalence can still be high in a domestic setting if preventative treatment is not implemented.

The prevalence of patent infection in a population of cats is not static, with shedding of ova being intermittent throughout an individual cat’s life. When considering the reduction of environmental contamination, therefore, the potential for adult pets to be reservoirs of infection should not be underestimated.

Although it has been proposed that people can be infected by eating the undercooked meat of paratenic hosts, such as wild game (Sturchler et al. 1990), the most common route of human infection is by the ingestion of embryonated eggs.

It was originally thought that T. canis alone was the source of human infection by this route but there is now strong evidence to suggest that T. cati is significantly involved as well (Fisher 2003). Exposure to T. cati eggs in the environment can occur primarily through one of two routes.

A combination of these routes and possibly direct contact with dog fur (Wolfe & Wright 2003) has led to significant numbers of people being exposed to the parasite, with surveys across Europe showing that between 2% and 31% of people have antibodies to Toxocara spp. (Overgaauw & Van Knapen 2013).

Fortunately, the incidence of clinical disease is relatively low. Currently approximately two cases per million people are reported in the UK each year. However, this is likely to be a significant underestimate of human toxocarosis cases overall. The wide variety of clinical manifestations make recognition of clinical toxocarosis difficult. Even when cases are confirmed, they may go unreported as it is not a notifiable disease and medical reporting is voluntary.

Although adult infections regularly occur, the most at-risk group are children, commonly between two and four years of age. This may be due to poorer hygiene, pica and geophagia in this group, or a greater susceptibility to infection.

Human toxocarosis presents predominantly in four manifestations:

There is some overlap between syndromes, with Toxocara seropositivity also being recognised as a risk factor for a number of distinct medical conditions. Associations have been made between Toxocara spp. infection and asthma (Buijs et al. 1997, Pinelli et al. 2008), eczema, epilepsy (Quattrocchi et al. 2012) and cognitive dysfunction (Walsh & Haseeb 2012).

As more risk factors and associations are made, and with a seropositivity in the UK human population of approximately 2% (HPA figure), it can be concluded that morbidity caused by human toxocarosis in the UK is an underestimated and significant problem. Therefore, practical control measures are important to reduce exposure to infection as much as possible.

With adequate control measures, human toxocarosis infection may be completely preventable. Control strategies for human toxocarosis involve a combination of measures and these have largely been centred around preventing T. canis exposure. Preventing T. cati exposure, however, is also important if control of human toxocarosis is to be achieved.

Despite extensive research, much is still unknown about the contribution of T. cati to human toxocarosis. Future research must concentrate on the relationship between sero-prevalence and zoonotic disease, differentiating between T. cati and T. canis infection in the human patient, and developing more cost-effective techniques for distinguishing between T. cati and T. canis ova in the environment.

Until more research in these areas is done, establishing the contribution made by cats towards this disease must be achieved from the bottom up through statistical modelling, prevalence studies and exposure to cats and cat defaecation areas as risk factors.

Veterinarians can play a role in carrying out prevalence studies in their patients through faecal examination as well as continuing to highlight the zoonotic risk to owners.

The irony is that although the physical and psychological health benefits of pet ownership are now rightly being recognised, the morbidity caused by chronic zoonotic infections such as toxocarosis goes largely unchecked and unquantified. In this respect, veterinarians have a vital role to educate the public and help reduce the incidence of disease.

*About ESCCAP UK & Ireland.

The European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) was formed in 2005. It is an independent not-for-profit organisation, comprising a group of eminent veterinarians across Europe, all with recognised expertise in the field of parasitology. ESCCAP is dedicated to providing access to clear and constructive information for veterinarians and pet owners with the aim of strengthening the animal-human bond. It works to provide the knowledge essential to help eradicate parasites in pets and the objective is to have a Europe where parasites are no longer a health issue for pets or humans.

ESCCAP UK & Ireland brings together the UK and Irish national associations of ESCCAP to form a group consisting of some of the leading experts in the field of veterinary parasitology. ESCCAP UK & Ireland works with pet owners and veterinary/animal care professionals to raise awareness of the threat from parasites and to provide relevant information and advice for the UK and Ireland.