23 Jan 2024

Ferran Sanchez considers useful diagnostic approaches for these conditions.

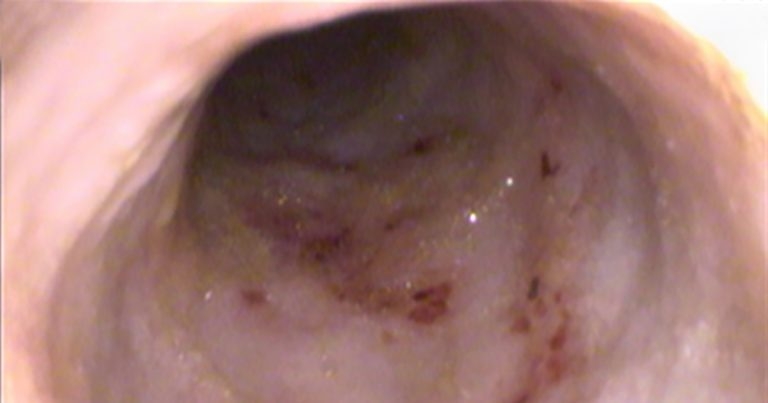

Endoscopic picture of the duodenum showing multiple superficial ulcers in a dog that presented with anaemia without macroscopic evidence for gastrointestinal bleeding.

Vomiting and diarrhoea are very common clinical complaints in small animal medicine, and, in a large number of cases, these signs are due to gastrointestinal (GI) conditions.

Depending on the age of the animal, the differential diagnosis list should be adjusted, taking into consideration the likelihood of each condition. In puppies, for example, infectious diseases such as parasites should be considered much higher on the list than in old animals, where inflammatory and neoplastic diseases are more frequent.

Using GI signs such as vomiting/diarrhoea as examples, the first goal in the diagnostic approach is to conclude if the origin is gastrointestinal (stomach, intestine) or extra gastrointestinal (pancreas, liver, and so forth). In this regard, on top of taking a good history and physical exam for clues locating GI disease (small intestine versus large intestine; Table 1) and/or suggesting extra gastrointestinal involvement (such as polyuria/polydipsia, which could raise more suspicion about an endocrinopathy or renal disease, or icterus for liver disease), biochemistry can be very useful.

| Table 1. Differences between small intestine and large intestine diarrhoea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Small intestine | Large intestine |

| Frequency | Normal/mildy increased | Increased |

| Urgency | No | Yes |

| Tenesmus | No | Yes |

| Amount | Large | Amount |

| Fresh blood | No | Yes |

| Melaena | Can occur | Can occur |

| Mucus | No | Yes |

| Weight loss | Yes | Can occur |

| Vomiting | Yes | Can occur |

Biochemistry can help with increasing/decreasing suspicion for renal disease, hepatic disease and endocrinopathies. Besides, it is important to know the albumin levels, as it can affect the treatment plan and the prognosis.

Faecal alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor concentration is an earlier marker of protein loss, and it can be useful when the cause of hypoalbuminaemia is not really clear from history or imaging1. Finally, vomiting/diarrhoea can cause electrolyte imbalances that may need supplementation, so it is important to get this information.

Different clinical indices exist (canine inflammatory bowel disease activity index; CIBDAI; canine chronic enteropathy clinical activity index; CCECAI) to evaluate the severity of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and monitor the response to treatment, which include clinical signs, physical exam findings and level of albumin. CCECAI has been associated with response treatment and outcome2.

Tests assessing the pancreas should also be considered, as a major overlap exists in the clinical signs that GI and pancreatic pathologies (pancreatitis or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency; EPI) can cause. For pancreatitis, canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI; quantitative) or 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid-(6’-methylresorufin) ester (DGGR) lipase can be evaluated. For EPI, trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) is the test of choice.

Hypoadrenocorticism is reported to cause GI signs only in a minority of cases3; however, this differential diagnosis should be kept in mind, and basal cortisol can be measured as a screening test. In older cats, hyperthyroidism can cause vomiting and diarrhoea, in half and one-third of cases respectively, so total thyroxine is a good test when this differential diagnosis is high on the list (sensitivity 91%, specificity 100%)4.

Cobalamin (vitamin B12) can be evaluated if uncertainty exists over the cause of the problems, or when a GI disease is confirmed, as it has therapeutic (needs to be supplemented in chronic cases) and prognostic implications. This vitamin used to be requested in combination with folate; however, little evidence exists about the significance (and need for treatment) for high/low folate in dogs and cats and, consequently, does not impact the management of cases. Besides, the most common brand for cobalamin supplementation also contains folate.

In puppies/kittens or individuals that have been recently in a high-population context (such as kennels), infectious diseases become more relevant:

For some conditions, multiple faecal samples improve the chances to detect an infectious agent.

Occult faecal blood has been used in the past in cases of anaemia for which GI bleeding is suspected, but no macroscopic evidence exists (no haematochezia or melaena), or imaging evidence of any underlying cause (such as the description of an ulcer). However, this test is not very practical, as a specific diet (hydrolysed or vegetarian) has to be fed for few days, and it is not considered the most reliable test in general1.

Dysbiosis index in faeces is quite a recent tool to assess the health of the gut microbiome. This test is useful to predict which cases may respond better to a faecal microbiota transplant (FMT), as a monitoring tool in dogs receiving FMT and also to select which dogs may be a better faecal donor5.

Imaging is a very important tool when GI disease is suspected. Abdominal ultrasound is a very good first-line option. It is more accessible and cheaper than abdominal CT, and it provides much more information than abdominal radiography. Besides, it allows fine-needle aspirates for sampling under ultrasound guidance, if indicated.

Some recent studies questioned the utility of ultrasound in cases of chronic diarrhoea – in one study, only in 15% of cases was ultrasound considered vital or beneficial, and it concluded that ultrasound was mainly useful in cases with considerable weight loss, palpable abdominal or rectal mass, decreased appetite or when a suspicion of neoplasia was present6. Looking at chronic vomiting, it was reported to be useful in one-quarter of cases, approximately – especially with increasing age or if final diagnoses was reported to be GI adenocarcinoma/lymphoma7.

These studies suggest that ultrasound in a majority of cases is not useful; however, it is the author’s opinion that if finances are not a concern, abdominal ultrasound is a very good first-line diagnostic tool to provide guidance about the most likely or unlikely cause(s) – especially before proceeding with endoscopy or certain treatment (such as immunosuppressants).

Upper and lower GI endoscopy have also been considered for a long time an important part in the diagnostic approach for GI disease – particularly in chronic cases. However, is it actually necessary in all cases? Or, let us word it in a different way: does the benefit overcome the risk? And also, nowadays, the cost?

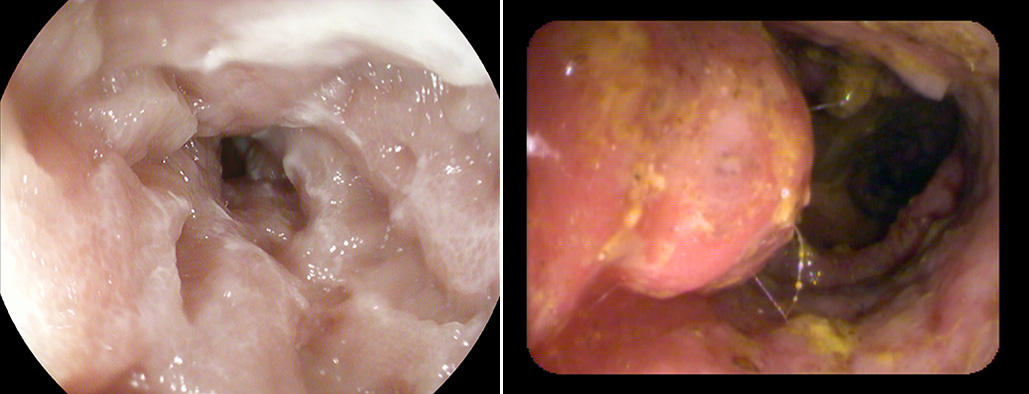

Let us start with an easy scenario. If a gastric mass exists for which ultrasound guided fine-needle aspirates have been considered not possible, appropriate (risk of seeding, perforation) or have been unrewarding, gastroscopy to obtain biopsies of the stomach is a good non-invasive option (Figures 1 and 2). To scope.

Let us have a break with an even easier scenario, for which no explanation is needed: a gastric foreign body for which endoscopic retrieval is considered feasible. To scope.

Now, let us go to the main dilemma, using an example of a middle-aged, cross-breed dog with chronic diarrhoea. Abdominal ultrasound is considered almost unremarkable, just mild thickening of the small intestine. How likely is that endoscopy/histology changes our course of action in comparison with setting it without these diagnostic tools?

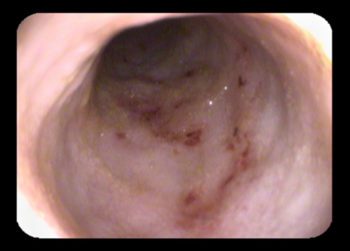

Often, the main goal when performing endoscopy is to take biopsies (Figure 3) to rely on histology to distinguish between inflammation and neoplasia. In an unpublished study (author’s communication) of 115 dogs with chronic diarrhoea without ultrasonographic findings suggestive of neoplasia, only in 2 out of 115 cases (1.7%) was neoplasia (lymphoma) the histological diagnosis made. This study agrees with the author’s clinical experience about the chances of endoscopy/histology revealing a neoplastic process, in dogs with chronic diarrhoea and “normal” abdominal ultrasound (and, consequently, altering the course of action in dogs with chronic diarrhoea), being low.

This information should be kept in mind when discussing benefits, risks and costs of endoscopy/histology with owners. Besides, the literature does not suggest a change in treatment/prognosis depending on the type of inflammation or severity of the inflammation.

However, other studies showed a slightly different conclusion. One study with 15 cases of GI lymphoma concluded a normal ultrasonographic appearance in one-quarter of cases (4 out of 15; 26.7%)8, and one study with 84 cases of intestinal lymphoma revealed an absence of ultrasonographic abnormalities in the intestines in 5 out of 65 (7.7%)9.

On the other hand, the conclusions of another research group focusing on the results of gastroduodenoscopy in dogs with chronic GI signs would challenge the utility of endoscopy in chronic GI cases. In that study with 195 cases, biopsies only revealed lymphoma in four (2%) and, among them, all three cases that underwent abdominal ultrasound had abnormalities reported10. Endoscopic score has been associated with outcome in one study2, so endoscopy can provide prognostic information (Figure 4).

To scope? To inform the owner about benefits and risks. If low anaesthetic risk, no financial concerns and no response to diet trial are all present, it is reasonable.

In cats with chronic GI signs, the need to obtain biopsies is also quite controversial, because if abdominal ultrasound only revealed non-specific changes, IBD or small cell lymphoma are the most likely diagnoses, and treatment and outcome are the same.

Colonoscopy is indicated in cases where granulomatous colitis (also known as histiocytic ulcerative colitis) is high in the differential diagnosis list, to confirm this condition, as it requires a different treatment (antibiotics) in comparison with the rest of inflammatory enteropathies.

Ulcerative colitis is common in the boxer and French bulldog, and it is caused by Escherichia coli. Colonoscopy allows for obtaining biopsies for histology, on which you can perform a specific stain called periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) that will reveal PAS positive macrophages if the condition is present, and it is a pathognomonic finding.

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) is another good tool to diagnose this enteropathy, as it proves the presence of E coli. Finally, a biopsy can be submitted for bacterial culture/sensitivity. This may be useful, as resistance to quinolones (common first-line antibiotic for this disease) has been reported. Granulomatous colitis, to scope.

Finally, colonoscopy is also indicated when rectal polyps/masses are present or suspected (Figure 5), to take samples and get a better description or understanding of how the lesion is. This may be useful to assess if surgery is possible. Besides, in cases of polyps or strictures, colonoscopy allows the performance of removal and balloon dilation, respectively.

If, in the end, endoscopy is elected, the next question is if gastroduodenoscopy and/or colonoscopy should be performed. History is very useful (Table 1) to try to locate the condition more specifically and, consequently, choosing the best diagnostic approach.

In the author’s experience, pure large intestine diarrhoea cases are quite apparent from history. However, a large percentage of cases exist where a combination of signs are present, and it is not possible to conclude the origin in a certain way, and the diarrhoea is considered mixed.

In these cases, the author’s advice would be to just perform upper GI scope, as it requires much less preparation (colonoscopy requires longer starvation, use of laxatives, enemas, and so forth), and performing only one procedure saves time (anaesthetic time for the patient and staff time), while performing only one procedure also decreases the cost.

In the literature, studies exist describing the disagreement between biopsies obtained from the duodenum versus the ileum in the same dog. However, in the majority of cases, this disagreement is about the type of inflammation, not about inflammation versus neoplasia, with this scenario only reported in few cases11,12.

Even if different types of inflammation are present in each location, this information (type of inflammation and severity) does not impact much on the management of the case.

Very briefly, endoscopic capsules provide ambulatory light imaging using a small capsule (11mm × 31mm) that can record 360° images, and also has an internal clock to stop recording when device is not moving.

The endoscopic capsule offers some benefits in comparison with endoscopy: it is less invasive (no need for anaesthesia, so it can be an option in patients where anaesthesia is considered to have a moderate/high risk) and may provide visualisation of the full GI tract. Besides, it also offers insights about the motility of the GI tract.

The main disadvantages are that, obviously, no biopsies are obtained, and also that it can only be used in dogs weighing more than 5kg. Equally, the risk exists of the capsule getting stuck in the stomach; this is not a medical risk (it is reported to move forward or backwards at some stage), but it implies a diagnostic failure, as the capsule stops recording at some stage or, if it is vomited, obviously does not provide images beyond the stomach.

Metoclopramide is advised to promote motility and decrease chances of capsule getting stuck in the stomach.

The endoscopic capsule can be combined with upper GI scope (which allows the taking of biopsies from the stomach and duodenum), and it can be placed directly in the duodenum.

Some cases where the author has used endoscopic capsules are cases of anaemia or GI bleeding that, after an extensive work-up, an obvious cause has not been found, and it can be useful to confirm the origin of the problem. Sometimes, endoscopy confirms the lesion, and the capsule is not placed to save costs (Figure 6).

It is important to bear in mind that even if ultrasound does not show any ulcers, it does not mean none are present, as the sensitivity of ultrasound has been reported to be low for non-perforated ulcers13.