17 Sept 2024

Kit Sturgess looks at how vets can work with owners and advise on ongoing canine care during the later years.

Image © Mary Lynn Strand / Adobe Stock

For many older dogs, the primary demand for veterinary care centres around chronic disease that is likely to advance over time. The key ways practices can work with the carers of senior dogs is to co-create a patient-centric plan.

Most chronic diseases do not have a linear course and will have periods when they appear quiescent and other periods where a flare-up occurs. Therefore, it is important to discuss with the client about what constitutes background therapy and to have a plan to manage when a flare-up is present.

So, for example, in a patient with chronic OA being generally well managed with NSAIDs, times may occur when the OA flares, such as after a longer walk over the weekend, in which case additional therapy such as paracetamol may be appropriate and the client needs to have guidelines about when they will use this rescue therapy at what level, and whether they should inform the practice.

Keeping in contact with owners of senior dogs with chronic diseases is really important as it is easy for this rescue therapy to become everyday treatment. Taking the aforementioned example, chronic paracetamol therapy is unlikely to be effective – and, therefore, if the time comes when NSAIDs are ineffective alone, the client should know a discussion needs to be had as to what additional multimodal therapy may be appropriate, such as bedinvetmab, gabapentin (used under the cascade), physiotherapy or acupuncture.

The most common chronic diseases that we encounter in our senior dogs are:

Many excellent articles review the treatment of the diseases listed, including chronic management and options for multimodal therapy. The purpose of this article is to look at the context of elder dogs that may have more than one disease and how being older affects the way the condition may be approached and managed.

As an individual ages, changes occur in all organs, increasing the likelihood of multiple organ dysfunction that impact on each other (a domino effect) and can prove challenging when deciding on therapy – for example, cardiorenal axis (Table 1). Generally, systems are less able to cope with sudden rapid change, whether that be of disease or treatment.

| Table 1. Impact of ageing on various body systems | ||

|---|---|---|

| Body system | Changes | Opportunities |

| Cardiovascular system | Reduced maximum cardiac output Increased risk of hypertension Likely increase in vascular stiffness |

Exercise Blood pressure screening Weight management |

| Musculoskeletal system | Reduced bone density Use-damage to joints Loss of muscular strength, endurance and flexibility |

Adequate calcium and vitamin D Exercise Physiotherapy/flexibility training |

| Gastrointestinal system | Structural changes in small and large intestine reducing absorptive capacity and digestibility | High quality, highly digestible diets Adequate micronutrients Palatable |

| Bladder and urinary tract | Bladder less elastic Urethral tone reduced Thirst receptors blunted Reduced sensation of bladder filling leading to urgency Increased incidence of UTI |

Ensure adequate fluid intake Provide increased opportunities to urinate Weight control Screening blood and urinalysis |

| Cognitive function | Reduced memory and problem solving Decreased flexibility |

Introduce change slowly Ensure some variation in routine Dietary supplements? |

| Sensory function | Reduced sense of smell and taste Deterioration in auditory and ocular function |

Ensure adequate lighting e.g. stairs Keep key parts of the environment consistent Give time to sense new environments Palatable food |

| Teeth | Dental and gingival disease common | Brush if possible Regular dental cleaning |

| Skin and coat | Thin, less elastic and more fragile Decreased barrier function and oil production Reduced grooming |

Careful choice of shampoo – mild and moisturising Get used to being groomed |

| Weight | Difficult to maintain ideal weight (Fig. 10) | Monitor weight Physical activity Appropriate diet |

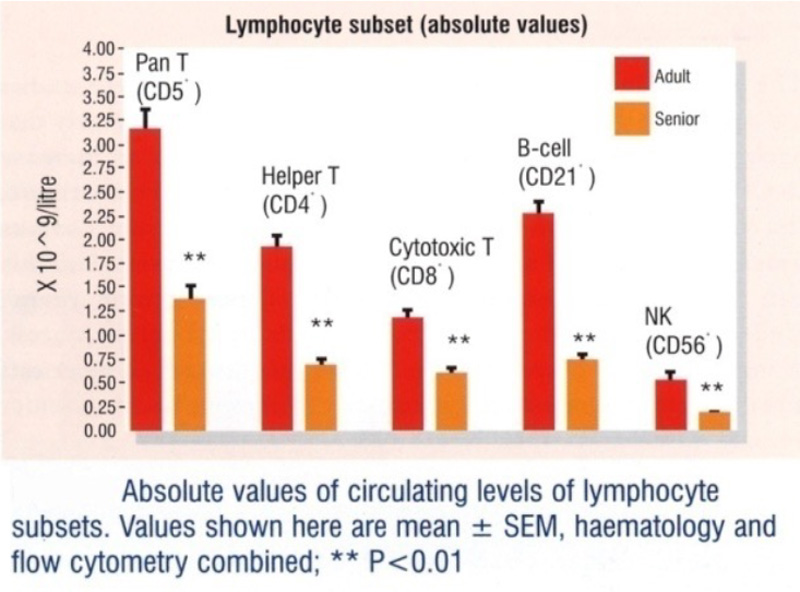

A number of studies have looked at the changes in the immune system of dogs as they age and have shown evidence that the immune response is less active and less well controlled (Figure 1). Although the biological impact of these changes is less clear, we do know that infectious and neoplastic disease is more common in older pets, and that wound healing is less rapid.

Figure 1. Impact of ageing in the immune system.

Good evidence shows that disease incidence and prevalence increases with age (Figure 2), and that age-related disease occurs earlier as dogs get larger (Figure 3).

As part of the care plan for senior dogs a discussion should be had as to the frequency of routine checks and what those checks might entail. This will depend on the chronic disease that the patient may have, the personality of the dog and financial constraints.

Poppy (Figure 4) is a 10-year-old neutered, female cockapoo that has a number of different chronic disease challenges, including inflammatory enteropathy, hepatopathy (vacuolar and mildly inflammatory), hypothyroidism and proteinuria. She has had a cholecystectomy in the past for a gallbladder mucocoele (Figure 5).

Poppy is a lovely dog, but she gets very anxious when she visits the veterinary clinic, so this means that we have to carefully plan visits to ensure minimum waiting time and also that all examinations and investigations are carried out in as efficient way as possible.

It also means more communication remotely, via email, and the owner has bought a set of weighing scales so that she can monitor Poppy’s weight going forward. Tests can also be performed without seeing Poppy, such as intermittent monitoring of her urine protein creatinine ratio.

As with any patient, sometimes it is difficult to do all the investigations that would be appropriate. For example, in Poppy’s case, we do not have a clear view as to what her blood pressure is, as trying to measure in the clinics does not give us a meaningful result and trying to hospitalise her for repeated measurements results in her becoming very anxious and distressed, usually ending up with a flare-up of her inflammatory enteropathy.

“Good care of elderly dogs does not necessarily mean greater spend, but it does mean ensuring a coordinated plan is in place and that any consideration for investigation or treatment change is taken in context with the other health conditions the patient may have, the patient temperament, the carer’s viewpoint and the financial implications.”

Although each individual senior dog requires a personal contextualised care plan, it is helpful to have a broad structure in the practice that outlines the process and gives a basic framework for what a senior health care plan may look like.

Not all of that plan needs to be in person – a number of quality of life (QoL) surveys can be used in older dogs to assess their general health and well-being over time, and some specific disease-related QoL surveys are also available. The practice guidelines can then be modified according to patient and carer requirements.

Another key issue with senior dogs that may be on multiple medications for a variety of different chronic diseases is that a good overview exists of the medications that have been prescribed, the possible interactions and side effects and the duration for which repeat prescriptions can be given.

It is also helpful to define somewhere in the practice management system a place where a summary of all the conditions that are being managed appear, what their status is, when the next check-up should be and what the proposed investigation is, current medications and the member of staff who is in charge of that condition. Ideally one member of staff should be assigned to oversee the whole of the care package to ensure coordination and that treatment for one problem is not likely to have an adverse impact on other issues the patient may have (Table 2).

| Table 2. A summary for a 12-year-old, neutered female Labrador retriever | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Status | Treatment | Monitoring |

| Elbow OA | Currently well controlled | ● Robenacoxib (40mg by mouth every 24 hours), glucosamine and chondroitin, and occasional tramadol ● Can have repeat prescriptions ● Adverse reaction to gabapentin – marked sedation |

● Carer monitoring activity, desire to go for walks, energy level, ease of standing and getting into car. Report at regular check-up ● Report specific lameness if it occurs |

| Degenerative disc disease | Currently well controlled | ||

| Hypothyroidism | Waiting follow-up thyroxine (T4) levels in four weeks following increased L-thyroxine dose | ● 0.4mg L-thyroxine by mouth every 12 hours ● Sufficient medication until after next blood test |

● Thyroxine level four to six hours post- medication in four weeks |

| International Renal Interest Society Stage II chronic kidney disease | Slowly progressive | ● Diet discussions ongoing with carer | ● Carer to monitor water consumption ● Report at regular check-up ● Repeat renal parameters in six months ● Monitor urine – see urinary tract infection (UTI) |

| Grade II mast cell tumour removed right rib 6 | Remission | ● No treatment | ● Carer and staff to monitor site |

| Chronic multidrug resistant coliform UTI | Currently culture negative |

● None ● Care with immunosuppressive drugs risk of recurrence of UTI |

● Carer to report if changes in urine occur – frequency, smell, colour. Free catch sample to be brought in for urine specific gravity, dipstick and sediment analysis if changes observed |

| Right-sided grade II to III harsh localised murmur – point of maximum impulse mid apex base | Observe | ● None | ● Carer to monitor activity (see OA) ● Cardiac examination at regular check-up ● Consider echocardiography if changes in activity or physical examination |

| Mild, bilateral incipient cataracts | Observe | ● None | ● Biannual ophthalmic examination ● Carer to report if changes in visual acuity noted |

| Weight loss and reduced appetite | Under investigation | ● Omeprazole 30mg by mouth every 12 hours ● Clinician to review weight chart and appetite updates before further prescription |

● Carer to monitor appetite and food intake ● Monthly weight check (see practice guidelines for response) ● Further investigation to be discussed at next routine check-up |

| Care with glucocorticoids – recurrence of UTI, cardiovascular disease, current NSAID use. | |||

Senior dog health care is a whole team effort and a variety of different types of check-ups can be carried out – for example, reception involved in regular weighing if that is appropriate; pharmacy in managing the prescriptions and drug dispensing; and nursing input in managing weight, diabetes, blood pressure and blood sampling.

A clear pathway should have been created to allow escalation of any issue that is unexpected. So, for example, changes in weight, with reception understanding their role is not just to record the weight, but to look at the trend and respond accordingly (Table 3).

| Table 3. An approach to weight loss | |

|---|---|

| Screen result | Action |

| <2% weight loss from last measurement but significant hyporexia | Consider diet change to improve palatability, recheck patient in 2-3 months |

| 2-5% weight loss without changes on initial screening | Increase calorie intake by 10-15%, consider change in diet to increase digestibility and institute monthly weigh-in |

| 2-5% weight loss with changes on initial screening but no localising signs | Perform detailed screening – further investigation of changes found; plan will depend on disease process involved |

| 2-5% weight loss with changes on initial screening and significant hyporexia | Perform detailed screen and consider a more complete dental examination under anaesthesia including radiographs |

| 5-10% weight loss regardless of screening results | Perform detailed screen – further investigation of changes found plan will depend on disease process involved |

| 10-20% weight loss regardless of screening results | Perform detailed screening and investigate changes found. If detailed screening is unremarkable extend screening further to include vitamin B12, TLI, cPLi, thoracic and abdominal imaging |

| >20% weight loss | Accurate diagnosis becomes important, intestinal biopsies may become necessary |

When dealing with senior dogs where multiple problems are likely to exist, extensive investigation is often not justified, so it should be clear what assumptions have been made – for example, a lame, elderly dog is assumed to have OA, behavioural changes are likely due to cognitive and the reduced urine concentration is likely to represent chronic kidney disease.

This means that if treatment is appearing ineffective, it may be that the right disease is being treated with a drug that is appropriate, but at the wrong dose; the disease has progressed, making monotherapy no longer effective; the assumed diagnosis is correct, but the drug chosen is ineffective in that particular patient; or that the dog’s lameness is not OA related.

This then may require a discussion with the client and carer about whether next steps involve drug change, or a point has been reached where further investigation is indicated and, if so, what that would mean. When planning further investigation it is important to refer back to the list of current patient problems so that if a blood sample has been taken, appropriate testing can be run that may not just cover the current question, but also address any ongoing monitoring.

Equally, if sedation or anaesthesia is likely to be necessary do other considerations for investigation or treatment, such as dental care, exist that would be appropriate to be carried out at the same time?

If it is not appropriate because of risk, then you should ensure the client is aware that it has been considered, but the balance of risk and benefit makes it inadvisable.

Good care of elderly dogs does not necessarily mean greater spend, but it does mean ensuring a coordinated plan is in place and that any consideration for investigation or treatment change is taken in context with the other health conditions the patient may have, the patient temperament, the carer’s viewpoint and the financial implications.

It is also important to have a clear view that can be communicated with the carer on the benefit that any change may bring, as well as talking to them about how they are coping with looking after the patient (caregiver burden).

Although a general practice approach to the care of elderly dogs should exist, each patient has to be treated as an individual and have its own care plan. Unfortunately, a real dearth of literature looking at the optimal ways of managing elderly patients with multiple comorbidities exists, so this leaves it very much up to clinical judgement.

Because most elderly dogs are less flexible in a physiologic sense, the author’s general approach is to make one change at a time and observe the response while trying to give the client some objective parameters that they can monitor to give you information on the impact of the change made.