20 Mar 2019

Ron Ofri discusses the causes of this eye condition and their clinical implications – as well as diagnosis methods, the aims of treatment and indications for surgical intervention.

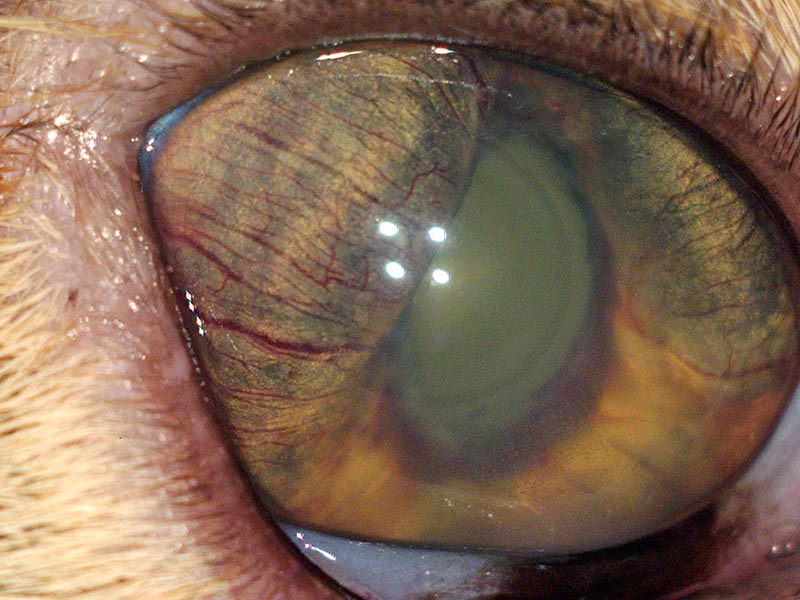

Figure 1. A hypermature, posteriorly luxated lens.

Glaucoma is a disease characterised by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). It is caused by reduced outflow of aqueous humour from the eye and may be inherited or secondary to another intraocular disease.

Clinical signs include chronic or acute pain, buphthalmos, episcleral congestion (“red eye”), corneal oedema and striate keratopathy. Pupils may be sluggish, or fixed and dilated. Damage to the retina will cause progressive loss of vision, leading to blindness. In the end stage of the disease, due to chronic elevation of IOP, the ciliary body may atrophy, causing decreased aqueous production, lowering of pressure and phthisis bulbi.

It is impossible to restore vision lost to glaucoma; the aims of treatment are preventing further loss of vision and decreasing pain. Primary glaucoma requires lifelong treatment. Owners must understand the aim of therapy is to stabilise IOP and that the disease is never cured. IOP may be lowered surgically or medically, using drugs that increase aqueous outflow (for example, latanoprost) or decrease production (for example, dorzolamide). However, prognosis for long-term control of pressure is poor, and veterinarians frequently need to enucleate blind and painful eyes.

The definition of glaucoma is rapidly changing as our understanding of the pathogenesis of damage to the retina and optic nerve improves. However, the disease can still be generally described as an elevation in intraocular pressure (IOP) incompatible with normal ocular function.

IOP is the balance between production and drainage of aqueous humour. In clinical practice, glaucoma is caused by drainage disturbances; cases of increased production are not recognised.

Aqueous humour is produced in the ciliary processes, from where it flows into the posterior chamber and through the pupil into the anterior chamber.

After circulating in the anterior chamber, and supplying the metabolic requirements of the lens and cornea, the aqueous exits the eye through the iridocorneal angle – between the cornea and iris – which is spanned by pectinate ligaments. The drainage continues through the uveal and corneoscleral meshworks, eventually exiting the eye into systemic venous circulation.

Aqueous may also exit the eye through an unconventional path, in which it diffuses through the iris and ciliary body (or through the vitreous) into the suprachoroidal space; from there, it drains into the venous circulation. The importance of this route changes between species – it accounts for 15 per cent of the total drainage in dogs and 33 per cent in horses, but only 3 per cent in humans.

Based on the cause, glaucoma may be classified in one of two ways:

Alternatively, it may be classified according to the state of the drainage angle. The angle may be open (in which case the obstruction is further downstream), narrow or closed.

These classifications are not mere semantics; rather, they have significant clinical implications. It is possible secondary glaucoma may be cured if the primary ocular disease is treated successfully – for example, surgical removal of a luxated lens. More importantly, if unilateral glaucoma is deemed secondary, it means the contralateral eye is not necessarily at risk.

On the other hand, cases of primary glaucoma will require lifelong treatment. Moreover, in patients presenting with unilateral primary glaucoma, the contralateral eye is highly likely to develop the disease – on average, within eight months. In some breeds, examination of the angle will help determine whether the eye is at risk of developing primary glaucoma.

The two classification methods complement each other, and in dogs it is possible to encounter all four possible combinations – primary open-angle glaucoma and secondary closed-angle glaucoma are examples.

Primary open-angle glaucoma is an inherited disease. It has been investigated extensively in beagles – in which it was shown to be an autosomal recessive disorder – but has also been documented in the Keeshond, Norwegian elkhound, poodle and other breeds.

As the name implies, the angle and pectinate ligaments are normal. It is assumed the outflow obstruction is in the uveal and corneoscleral meshworks, and is the result of biochemical changes in the basement membrane of these regions.

The disease is chronic in nature, with IOP increasing slowly over months or years. Though dogs may present with buphthalmos, or even with secondary lens luxation, vision is frequently retained in advanced stages of the disease.

Primary narrow-angle glaucoma is an inherited disease in numerous breeds, including the American cocker spaniel, cocker spaniel, flat-coated retriever, Labrador retriever, golden retriever, basset hound, Samoyed, chow chow, great Dane and Siberian husky.

A developmental abnormality results in the formation of dysplastic pectinate ligaments, which can be seen as sheets of tissue spanning the drainage angle. In the first years of life, aqueous exits the eye through flow holes in the sheets, but these eventually fail – resulting in IOP elevation.

Most patients present with an acute attack of glaucoma – including congestion; oedema; fixed, dilated pupils; and loss of sight. Though only one eye may initially be affected, both eyes should be carefully evaluated and treated. Individual attacks may be successfully treated, but progressive angle narrowing and closure may develop, and the long-term prognosis for vision is guarded.

In secondary glaucoma, pressure rises due to an obstruction in aqueous outflow caused by another ocular disease. The common ocular diseases that cause secondary glaucoma are:

In most animal species, normal IOP range is between 15mmHg and 25mmHg. Elevation in IOP is defined as glaucoma, while low IOP is usually a sign of uveitis due to increased unconventional outflow. IOP should be similar in both eyes. Differences greater than 10mmHg between eyes may also indicate glaucoma.

IOP cannot be measured digitally with one’s fingers. It should be recorded using a Schiøtz indentation tonometer – or, preferably, with modern rebound or applanation tonometers.

It is important to examine the angle to determine the risk of glaucoma (in breeds with goniodysgenesis or primary glaucoma, or if the other eye has developed the disease).

The state of the angle may also dictate treatment – no point exists in giving drugs that open the angle in cases of open-angle glaucoma, or in cases of goniodysgenesis. Drugs that reduce aqueous production, or increase unconventional outflow, may be more suitable in such cases.

Gonioscopy is performed by a specialist using a goniolens placed on the cornea. The lens refracts outgoing light – allowing the specialist to visualise the entire angle and classify its state.

Glaucoma is a disease that may affect all ocular layers and structures.

The aims of glaucoma treatment are preventing further loss of vision and decreasing pain caused by IOP elevation. It is impossible to restore vision lost due to glaucoma.

Primary glaucoma requires lifelong treatment. Owners must understand the aim of the therapy is to stabilise the IOP and that the disease can never be fully cured.

Diagnosis of primary glaucoma in one eye mandates prophylactic treatment in the other eye. In uncertain cases, referral to a specialist for gonioscopy should be considered.

Osmotic diuretics are not used for long-term treatment of glaucoma. Instead, they serve for emergency lowering of pressure in cases of acute attacks. The most commonly used drug in this category is mannitol (1g/kg to 2g/kg IV). The fluid is administered slowly for 30 minutes, and water is withheld for 3 to 4 hours.

Prostaglandin analogues act by increasing the unconventional outflow. They are most effective in dogs because their effect is independent of the state of the angle, which is frequently blocked. They are ineffective in cats, which lack the receptor, and contraindicated in uveitis.

Latanoprost, travaprost and other drugs in this category are given once or twice daily.

Carbonic anhydrase is a key enzyme in the production of aqueous humour, so its inhibition will result in lower production and decreased IOP. Like prostaglandin analogues, this effect is independent of the state of the angle.

The topical form of the drug – for example, dorzolamide and brinzolamide – has none of the systemic side effects observed with systemic drugs. It is given twice daily.

Systemic drugs, such as acetazolamide (10mg/kg) and methazolamide (2.5mg/kg to 5mg/kg) are given twice to three times daily. They may cause metabolic acidosis. Monitoring of side effects and potassium levels is mandatory, and they are not well-tolerated in cats.

Topical miotics increase drainage by opening the iridocorneal angle, through contraction of the iris and ciliary muscle. The most commonly used drug in this category is pilocarpine (one per cent to four per cent, twice to three times daily).

Beta-blockers are sympatholytic drugs that lower aqueous production by reducing flow of blood to the ciliary body. They are commonly used in humans, but their effectiveness in animals is controversial. Systemic side effects are common in small dogs, cats and animals with pulmonary or cardiovascular diseases. Drugs in this category include timolol, levobunolol and betaxolol (use once or twice daily). A preparation containing timolol and dorzolamide is commercially available and may be very efficacious.

Referral ophthalmology clinics may perform surgery to increase aqueous outflow – usually by implanting drainage tubes in the eye – or decrease aqueous production through partial destruction of the ciliary body, using laser or cryotherapy. However, treatment (surgical or medical) often fails – and the practitioner is faced with a blind, painful eye. Patient welfare requires the removal of this eye, through enucleation.

Owners of dogs with primary (but not secondary) glaucoma may be offered evisceration – implanting a prosthesis in an empty scleral “shell” – to provide a more cosmetic appearance.