30 Apr 2018

James Warland and Kelly Bowlt-Blacklock look at evidence and recommendations for use of antimicrobials in companion animals, in this first in a series.

Image © pimmimemom / Adobe Stock

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), particularly of bacterial infections, has become a globally important issue that threatens modern medicine. While understandable focus in the media is on human infections, AMR will affect our ability to adequately treat infections in companion animals.

The development of resistant organisms in veterinary species may also facilitate animal-to-human transmission of pathogens or resistance mechanisms, meaning responsible use of antimicrobials in animals is vital to ensure continued efficacy in human medicine.

This three-part series will look at the evidence and recommendations for antimicrobial use in veterinary practice. In part one, the context of AMR in companion animal practice and broad strategies for improving antimicrobial stewardship will be discussed.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), particularly of bacterial infections, has become a globally important issue that threatens modern medicine.

It is recognised AMR patterns can spread between bacteria affecting companion animals and humans1. While understandable focus in the media is on human infections, AMR will affect our ability to adequately treat infections in companion animals.

Voluntary efforts to improve antimicrobial prescribing patterns are vital to ensure legislative controls are not necessary; these could severely restrict the access vets have to antimicrobials, potentially significantly impacting modern veterinary practice.

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss mechanisms of resistance development in detail. Resistance does not develop because of the antimicrobials, per se, but rather the use of antimicrobial treatment selects for organisms that are resistant within the population by creating a selective pressure. It is important to remember this selection pressure will be exerted on both the pathogen being targeted and any other exposed population, including commensals. The main reasons for resistance developing are:

The development of resistant organisms in veterinary species may also facilitate animal-to-human transmission of pathogens or resistance mechanisms, meaning responsible use of antimicrobials in animals is vital to ensure continued efficacy in human medicine.

The World Health Organization (WHO) produces a list of “critically important antimicrobials” for human health, which provides context for considering which antimicrobials should have their use restricted. The latest (2017) version2 places highest priority on:

Vets will particularly recognise quinolones and third generation cephalosporins as antimicrobials commonly used in companion animal practice.

Two “big data” studies have been produced that consider antimicrobial use in dogs and cats in UK veterinary practice. Using the Small Animal Veterinary Surveillance Network (SAVSNET), Singleton et al3 found antimicrobials were prescribed in 18.8% and 17.5% of consultations for dogs and cats, respectively. Systemic antimicrobials were prescribed in 64.5% (dogs) and 84.5% (cats) of these consultations. Encouragingly, over the two-year period of study (2014 to 2016), antimicrobial use did decrease. Overall, 28.4% of dogs and 23.3% of cats received an antimicrobial over the two-year period.

Studying an earlier time point (2012 to 2014), and using a different practice network (VetCompass), Buckland et al4 found similar results, with 25.2% of dogs and 20.6% of cats receiving antimicrobials over the two-year period. Interestingly, Singleton et al found significant correlation between prescription of antimicrobials in dogs and cats at different practices, suggesting practice policy or clinicians’ preferences are likely to influence prescribing practice; this finding could also reflect variations in disease prevalence or risk in different geographical locations.

Amoxicillin-clavulanate represented the most commonly prescribed antimicrobial in dogs (28.6%), with cefovecin the most common in cats (36.2%). Given cefovecin represents a third generation cephalosporin, this led to the alarming finding 39.2% of antimicrobials prescribed to cats were considered highest priority, critically important antimicrobial agents (HPCIAs), as identified by the WHO. In dogs, fluoroquinolones represented 4.4% of all antimicrobial use, leading to 5.4% of the prescriptions representing HPCIAs.

Although this survey provides interesting quantification, it is difficult to assess the appropriateness of individual prescriptions. It is notable the most common reasons for prescription of antibiotics included pruritus, likely related to pyoderma or otitis; respiratory disease, particularly in cats; trauma in cats, suspected to relate to cat bite abscesses; and gastroenteric disease, which, in the authors’ experience, is most appropriately usually not treated with antimicrobials.

The use of cefovecin in feline patients has been examined5. Only 0.4% (5/1,148) of cases had samples taken for bacterial culture and sensitivity, with a further 14 cases having this testing recommended, but declined by the owners. Again, it is difficult to assess the appropriateness of the prescription, but it was used in 157 urinary cases, with half less than 10 years old, and, therefore, unlikely to have a bacterial urinary tract infection. In only 12% of cases was a justification given for the use of cefovecin over alternative antimicrobials in the clinical notes.

A study considered the prescribing patterns of Belgian vets via a questionnaire of common first opinion clinical scenarios and compared these to national guidelines6. Only 18.4% appropriately prescribed antibiotics (that is, prescribed antimicrobials when indicated, and didn’t when not indicated) in all of the five scenarios, and less than half (48.3%) complied in 4 out of 5 cases.

In this same survey, a quarter (25.4%) of antimicrobials prescribed first-line were higher tier antimicrobials (third and fourth generation cephalosporins or fluoroquinolones) that should be reserved for difficult cases, and in only 12.4% of prescriptions of these highest tier antimicrobials was their use supported by culture and sensitivity testing. Although it is possible differences exist between prescribing patterns in the UK, it seems likely these results, from a European neighbour, are relevant.

Evidence from studies of these suggested, despite growing concern about the importance of good antimicrobial stewardship, companion animal vets prescribe antimicrobials in a large proportion of consultations and they are frequently used inappropriately.

The Small Animal Medicine Society and BSAVA, together, produced guidelines for vets, and the authors would encourage all readers to consult this document and introduce the recommendations into their practice. The guidance includes a poster, which can be used to formulate a practice prescribing policy7.

The RCVS Code of Professional Conduct places responsibility on all vets to prescribe antimicrobials responsibly8. The often prescriptive licensing of veterinary medicines is sometimes cited as a reason for use of antimicrobials that should be restricted, such as fluoroquinolones, in companion animal veterinary practice. The VMD clarified its position with a statement9 it “considers that it is justified, on a case-by-case basis, to prescribe an antibiotic on the cascade in the interests of minimising the development of resistance”.

Particularly, if culture and sensitivity data supports it and the pharmacokinetics are understood, it is reasonable to prescribe antimicrobials using the cascade to achieve good antimicrobial stewardship. As with other prescribing decisions, the responsibility for decision-making lies with the vet and they must be able to justify their use of the cascade.

While reduction in the overall use of antimicrobials is a mainstay of good stewardship, this cannot be considered the only aspect to improving practice, and using antimicrobials in the most rational way is also important.

The authors encourage the development of a practice policy into which all interested parties have contributed. This can significantly improve the empirical use of antimicrobials.

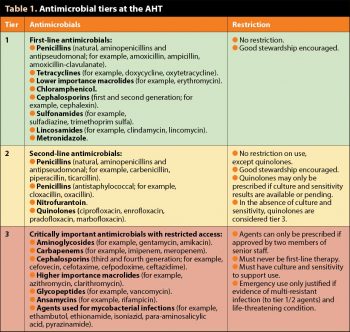

As an example, at the authors’ institute (the AHT), antimicrobial use was restricted to three tiers, with limitations on the prescription of higher tier agents (Table 1). While acknowledging this system is unlikely to be directly appropriate or practical for use in most first opinion practices, the authors believe a modified version of this system, with similar restrictions, would be a valuable method to reduce unnecessary antimicrobial use.

Many conditions presenting in small animal practice, for which antimicrobials are prescribed, are not caused by bacteria, such as feline cystitis, and antimicrobial use is unjustified. Even bacterial infections are often self-limiting, with no specific antimicrobial therapy, such as in bacterial gastrointestinal infections or canine upper respiratory tract infection with Bordetella (kennel cough).

In cases where a strong suspicion for a bacterial infection does not exist and delay in treatment is not likely to cause any significant detrimental effect, then antimicrobials are not justified.

It is vital to consider the bacterial pathogens likely to be causing the disease and what their likely susceptibility is.

Similarly, tissue penetration must be considered when seeking effective treatment; for example, the prostate is not effectively penetrated by penicillins/cephalosporins and, therefore, treatment of entire male dogs with urinary tract infections using amoxicillin-clavulanate is inappropriate, even if culture and sensitivity data supports its use.

Cytology, for example, of otitis externa or pyoderma, can provide evidence of a bacterial infection and the type of bacteria present. This often will help to narrow the choice of appropriate antimicrobial therapy and assist with empirical choices.

Culture and sensitivity data provides the best evidence for which antibacterial to use, and this information can be used either to guide initial therapy or refine therapy after initial empirical choices; if possible, it is ideal to narrow the spectrum of the agent(s) using this data. It is important to consider sensitivity data alongside the clinical picture, including scenarios or tissues where an agent may reach very high or very low concentrations.

While the clinical focus is on the pathogen being targeted, consider that systemic antimicrobials will expose the entire microbiome, including the commensals within the gastrointestinal tract and skin, to the prescribed treatment.

Development of resistance within these populations may produce resistant pathogens in a different context, or allow the transfer of resistance plasmids to other organisms, leading to resistance in these bacteria; this may affect the original pet, or be passed to other animals, humans or the environment. The use of topical treatment, particularly for otitis externa and superficial skin infections, reduces exposure of the entire microbiome to this effect.

Antimicrobials should never replace good hygiene and use can be reduced with preventive medicine.

Appropriate use of antimicrobials for surgical prophylaxis will feature in part three of this article. The routine use of antimicrobials for routine, sterile surgery should be avoided, with emphasis placed on achieving impeccable sterility in theatre, and keeping surgical wounds clean with good husbandry and handling postoperatively. Some bacterial infections in dogs, such as Leptospirosis and Bordetella bronchiseptica, as well as conditions that may lead to severe disease and consequent antibacterial use, such as canine parvovirus or feline panleukopenia virus, can be effectively prevented with vaccination.

Similarly, prevention of several bacterial infections can be provided through judicious ectoparasite protection, such as feline haemotrophic mycoplasmas (fleas) and Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi; spread via ticks).

Pyoderma represents one of the most common causes of antimicrobial prescription in small animal practice, but rarely occurs as a primary complaint. Appropriate management of the underlying cause, such as atopic dermatitis, can drastically reduce the requirement for future antimicrobial therapy. Particularly, in the face of recurrent infections, an underlying cause should be considered and addressed.

When treating bacterial infections, the narrowest spectrum agent that will sufficiently treat the infection should be used. Practically, this often means broad initial treatment can be narrowed using culture and sensitivity data, when available.

The relative importance of different classes of antimicrobials should be considered. The authors would advocate reserving the use of higher tier antimicrobials for:

The authors are grateful to Jeanette Bannoehr for her advice on the dermatology section and Sarah Caddy for reviewing the manuscript.

The AHT Antimicrobial Use Policy was drawn up by the AHT Infection Control Committee, with guidance from the RVC Infection Control Committee; the authors are grateful to both committees, and, particularly, Rosanne Jepson, for allowing the reproduction of sections of these policies in this article.