21 May 2018

Francesco Cian takes the ultrasonographic image of an 11-year-old domestic short-haired cat as inspiration for his latest Cytology Corner.

Figure 1. An ultrasonographic picture of a small intestinal wall thickening with loss of normal layering in a cat.

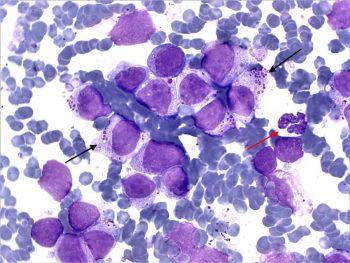

The ultrasonographic image (Figure 1) is from an 11-year-old domestic short-haired cat with a clinical history of lethargy and anorexia. A segmental, small intestinal wall thickening with diffuse loss of layering was noted. A fine needle aspirate (FNA) was collected and submitted for analysis (Wright-Giemsa, 100×; Figure 2).

The submitted smear has adequate cellularity and preservation. The background is clear, with frequent red blood cells, often clumped, a few bare nuclei and free magenta granules. It has a main population of large, discrete cells, likely lymphoid in origin (black arrows) – these have moderate amounts of lightly basophilic cytoplasm, with distinct borders, often containing small numbers of round magenta granules.

Nuclei are round, occasionally slightly indented and irregular, paracentrally located, with granular chromatin and small, round nucleoli occasionally seen. Occasional neutrophils (red arrow), likely blood derived, are also noted.

Large granular lymphocyte (LGL) lymphoma is a morphologically distinct form of high-grade lymphoma, frequently affecting the feline species and most often involving the gastrointestinal tract (in particular jejunum and ileum) and/or mesenteric lymph nodes.

Blood and/or bone marrow involvement are common findings at the time of the diagnosis. This form of lymphoma has generally been associated with negative FeLV and FIV serology.

Neoplastic cells origin from a subset of intraepithelial intestinal lymphocytes and have characteristic intracytoplasmic magenta or azurophilic granules, which may vary in numbers and sizes. LGL cells are grouped in two major lineages based on phenotype: T-cell (CD3+, CD5+, often CD8alpha-alpha+, and rarely CD4+) and less often natural Killer, the latter negative to all T-cell and B-cell markers.

In the feline species, LGL lymphoma has a particularly aggressive biological behaviour with poor prognosis and is only minimally responsive to standard lymphoma chemotherapy protocols. This differs from LGL neoplasia in humans and dogs, where a predominance of indolent forms has been described.

Overall, the identification of LGL lymphoma in cats is important clinically, as other forms of gastrointestinal lymphoma – especially small cell types – have a more protracted course.