24 Sept 2018

Sophie Keyte and Tom Harcourt-Brown look at the arguments for managing the disease medically or surgically and urge vets to offer owners all options.

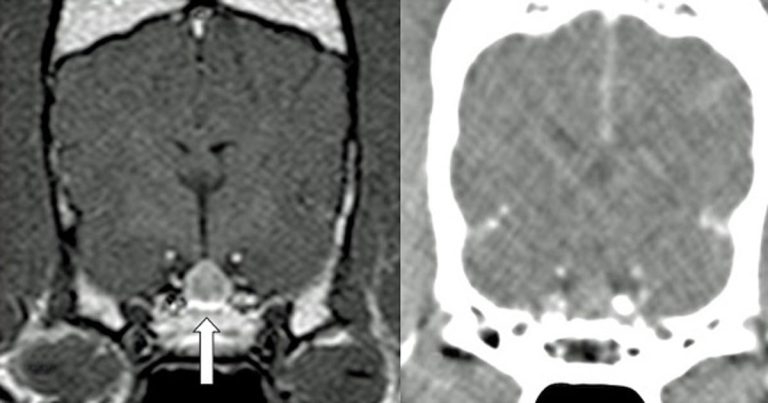

Pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism (HAC), also known as Cushing’s disease, affects approximately 1 to 2 in every 1,000 dogs (O’Neill et al, 2016; Figure 1).

It is a disease that, if left untreated, leads to poor quality of life, multiple comorbidities and neurological signs (for example, altered behaviour and seizures) secondary to pituitary tumour growth.

The treatment paradigm in the UK is to use adrenal-directed medical therapy, but in humans, pituitary tumours are considered a surgical disease if causing clinical signs (Nieman et al, 2015), and a growing body of evidence indicates this is a safe and effective procedure in dogs, too (van Rijn et al, 2016) – perhaps safer in the long-term than adrenal-directed therapy. In this article the authors present the arguments for surgical or medical management of pituitary tumours and consider whether pituitary-dependent HAC should be considered a surgical disease.

The mainstay of treatment in the UK has been medical with therapy directed towards the adrenal gland through destruction of the adrenal cortex (mitotane) or, in more recent years, competitive inhibition of steroid synthesis using trilostane. However, treatment and the need for regular monitoring of such patients can be costly, challenging (that is, accurate dosing with limited tablet size options and availability of synthetic adrenocorticotropic hormone), frustrating and time-consuming for the owner.

The side effects of medical management are serious and potentially life-threatening, such as iatrogenic hypoadrenocorticism. In addition, some think removal of negative feedback of excessive cortisol on pituitary adenomas during medical management of Cushing’s disease can lead to more rapid pituitary tumour growth and expansion. Previous studies have demonstrated the degree of enlargement of pituitary corticotrophic adenomas is dependent on the loss of inhibition by glucocorticoids (Kooistra et al, 1997).

Despite this, the effects of trilostane therapy are largely reversible, non-invasive and have been shown to control clinical signs in large numbers of dogs, with many vets having experience with this treatment modality. However, trilostane therapy does not deal with the underlying disease process – which is, essentially, for owner understanding, a brain tumour – and long-term prognosis with medical management, based on three-year survival, is poor (29%; Fracassi et al, 2015).

Available literature is limited regarding the long-term outcome of radiotherapy for the treatment of pituitary-dependent HAC in dogs. However, the onset of effect is slow and the limited availability also limits its usefulness in the clinical setting. It may be considered a useful option in the face of larger pituitary adenomas, such as those extending up to the interthalamic adhesion, where surgical risk may be considered to be higher (Sato et al, 2016), or with owners declining surgical intervention.

A single study reported a three-year survival of 55% in dogs with pituitary macroadenomas treated with radiation therapy; however, roughly 50% of the dogs included in the study did not achieve biomedical or clinical control of their disease (one of the main reasons for euthanasia in dogs with Cushing’s disease; Kent et al, 2007). Therefore, the use of concurrent medical management should be expected in many dogs treated with this modality.

The most compelling argument for the surgical treatment of pituitary-dependent HAC comes from the work of Bjorn Meij at Ghent University during the past 20 years. The researcher’s most recent publication (van Rijn et al, 2016) is the largest study of its kind, with just in excess of 300 dogs having undergone this procedure.

They reported a 91% survival at 4 weeks postoperatively with 92% remission rate; mortality was acceptable at only 9% – with a significant bias for larger tumours having a higher risk.

A 27% recurrence rate occurred over the follow-up period, similar to earlier studies. The survival rate and recurrence was significantly negatively correlated to pituitary size, indicating dogs with larger pituitary tumours at the time of surgery had a worse long-term prognosis when compared to dogs with non-enlarged pituitaries.

The overall size of the tumours on which surgery was attempted increased throughout the study period. This is likely, in part, due to bias with referring vets promoting hypophysectomy for dogs already with large tumours or neurological signs, but also surgeon experience and growing confidence with the procedure. Although larger tumours were reported to have a less favourable prognosis, the overall outcome improved over time. An earlier study (Hanson et al, 2005) reported a three-year survival of 72%, which is much better than those reported for medical or radiation therapy.

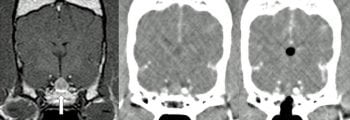

It is important to recognise complete removal of the pituitary gland is usually performed (Figure 1); therefore, these patients require lifelong supplementation of thyroxine and cortisone. All patients require immediate postoperative desmopressin administration, but, in most cases, this can be weaned in the first few months following surgery. Of course, complications are possible, which include incomplete tumour removal, haemorrhage, infection and recurrence. As such, owners need to be fully informed prior to choosing this treatment modality for their pet.

A large amount of the risk relates to surgeon experience and the postoperative care team who manages the endocrinological complications. Therefore, this technique should only be performed in facilities with this experience. The more widespread availability of advanced imaging, such as CT – and multidisciplinary expertise for preoperative, surgical and postoperative care of patients now available at referral centres – has made hypophysectomy much more accessible for referring vets and their clients.

No studies exist directly comparing surgery to medical management of pituitary tumours. Comparison of retrospective studies of different treatment modalities is difficult because of a tendency to include both microadenomas presenting with signs of endocrine disease and macroadenomas presenting with signs of neurological dysfunction. However, comparison of one, two and three-year survival rates with trilostane therapy for all pituitary-dependent HAC cases, versus surgery for pituitary-dependent HAC caused by both macroadenomas and microadenomas, provides compelling evidence that a real long-term benefit to surgery exists, balanced by a slightly higher short-term risk (Table 1).

We would therefore encourage vets to ensure they offer all available options to owners at the time pituitary-dependent HAC is diagnosed, including a discussion on hypophysectomy. Ideal candidates to consider for referral would include those cases with suspected/confirmed pituitary-dependent HAC not already started on trilostane therapy, with/without neurological signs or significant comorbidities and clinical signs which, in the owner’s mind, are greatly affecting the quality of life of their beloved pet (Figure 1).