28 Nov 2016

Lisa Weeth considers modern thinking on how diet impacts on a variety of health aspects in canine and feline breeds.

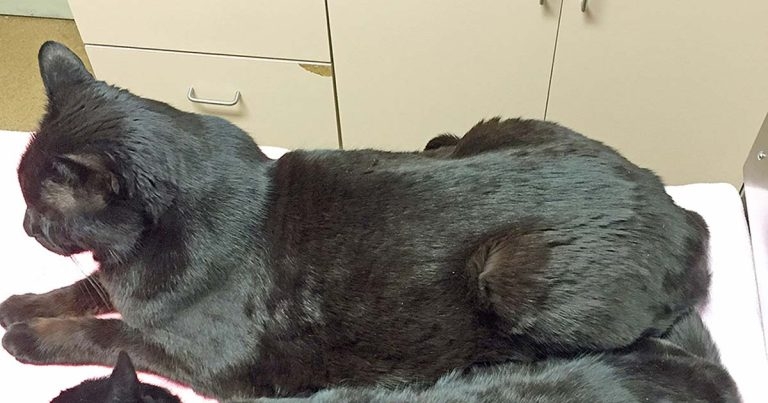

The same cat as above right, six months after changing to a diet with higher phenylalanine and tyrosine content.

The domestication of dogs began more than 30,000 years ago1, but many of our modern breeds have more recent origins within the past 200 years.

Archaeological and genetic evidence indicates cats began living with humans approximately 12,000 years ago – presumably after the shift in food production from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to that of farmed (and stored) agricultural products2. However, most modern cat breeds, as we know them today, originated only within the past 50 years3.

The popularity of selectively bred dogs versus randomly bred cats is reflected in the pet population statistics for the UK. While crossbreed and domestic top the list of dog and cat breeds, respectively, the next most popular breeds for dogs are Labrador retriever, Staffordshire bull terrier, Jack Russell terrier and Yorkshire terrier, while the next four most popular cat breeds are no breed identified, British shorthair, crossbreed and Persian4.

While breed-specific diet marketing is often just that – marketing – selective pressures imposed by human aesthetics for the past 200 years have caused unintended consequences on the requirements for certain nutrients, as well as changes in overall intestinal physiology5 that may be, optimally, addressed through feeding a more targeted diet.

Nutrients (vitamins, minerals, proteins, fats and carbohydrates) are required either for normal body functions or to serve as a precursor for additional compounds, proteins or hormones produced in the body. All dogs, irrespective of phenotypic variation, have the same essential nutrient requirements. However, in the past few decades, differences in nutrient metabolism and physiology between representative breed lines have been identified, and can affect skeletal development, skin and coat health and general gastrointestinal physiology.

The potential for feline breed-specific nutrient requirements has not been given the same level of attention, though extreme facial morphology of certain breeds, as seen in Persians, has been found to affect prehension and acceptance of certain diets6, and differences in coat length and colour influence the requirement of certain key essential nutrients.

Large and giant breed puppies are especially sensitive to dietary imbalances during the first year of growth. Excessive calcium intake can lead to developmental orthopaedic diseases and long bone deformities7,8, while too rapid a skeletal growth rate from excess calcium and energy intake can lead to painful osteochondrosis lesions in the joint or inflammation of the tissue surrounding the growing bones (panosteitis)9. These pathologic changes with excess calcium intake have not been seen in developing kittens.

For the rest of the essential minerals (phosphorus, magnesium, manganese, sodium, potassium, chloride, molybdenum, selenium, zinc, copper, iron and iodine) and vitamins (thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, pyridoxine, cobalamin, folic acid, choline, and vitamins A, D, E and K) a relative consistency in nutrient requirements exists for both growing animals and healthy adults.

The essential fatty acids – linoleic acid (LA; and omega-6 long-chain fatty acid) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA; and omega-3 long-chain fatty acid) – are required in the diet to maintain a supple skin and hair coat. Long-coated breeds have a higher requirement for these two nutrients to maintain coat quality and lustre, compared to their short-coated counterparts – likely due to varying levels of ceramide production5,10.

Arctic dog breeds are also at risk of zinc-responsive dermatitis due to decreased intestinal absorption of zinc11, whereas black coat variants of any breed (cat or dog) require higher intakes of phenylalanine (an essential amino acid) and its associated metabolic product tyrosine (a non-essential amino acid) to produce adequate levels of melanin to maintain a solid black hair colour12,13.

Taurine is incorporated into the retina and cardiac muscle, and is required for normal ocular and cardiac health. All cats, irrespective of breed, are unable to synthesise sufficient levels of taurine from the sulphur amino acid precursors, methionine and cysteine, and have an absolute requirement for pre-formed taurine in the diet. Conversely, dogs as a species are able to synthesise adequate levels of taurine from dietary precursors, with notable exceptions under certain circumstances. After a cluster of large breed dogs developed taurine-deficient cardiomyopathy while eating what appeared to be complete and balanced commercial adult dog foods14, investigators found certain breeds appeared to have a lower overall synthesis of taurine15-17, and taurine deficiency could develop if low total dietary protein was coupled with a higher fibre intake, causing increased taurocholic acid loss from the gastrointestinal tract18.

When comparing general disease prevalence among populations of dogs, larger breeds appear to suffer from more gastrointestinal disorders than small and medium breeds5. This may be related to the fact total gastrointestinal transit time and faecal quality have been found to vary with body size across all breeds19,20 – with larger breeds having higher faecal water content and faster transit times overall.

More recent work looking at the effect of specific macronutrient component of the diet on faecal quality has found breed-specific differences in the fermentation characteristic of undigested protein, resistance starch (undigested dietary carbohydrates) and dietary fibre21,22. These findings suggest the diets necessary to maintain optimal intestinal health and stool quality in large breeds, such as German shepherd dogs and Labrador retrievers, are different than those needed by small to medium-sized breeds.

All commercial pet food packages are required to list feeding guidelines based on a given bodyweight of dog or cat. These amounts are reported as the daily energy requirements and are calculated for a healthy animal using the formula 1.6 × (70bw[kg]0.75) for dogs and 1.2 × (70bw[kg]0.75) for cats23. The problem with calculated requirements is individual animals will vary by up to plus or minus 50 per cent of these values, and while less variation exists among cat breeds, there can be dramatic differences in dog breeds, with large and giant breeds often having lower daily energy requirements on a metabolic bodyweight basis during growth and maintenance compared to small to medium-sized breeds24,25.

The understanding of nutrient absorption, interaction and optimal intakes for dogs and cats has grown dramatically in the past 100 years. Early nutritional research was focused on identifying minimum requirements for growth and reproduction, and preventing signs of deficiencies, while more current research seeks to optimise long-term health and wellness in adults, as well as to use nutrient modifications to manage disease states.

With advances in manufacturing technology, growth in the field of nutrigenomics and identifications of breed-specific nutritional requirements, a wide range of commercial diets are available that can optimise health and wellness for companion dogs and cats, and breed-specific diets are among them.