14 Jan 2020

John Beel, BVSc, CertVOphthal, MRCVS, Elizabeth Kwint, BVetMed, GPCert Bus Admin, MRCVS, and Jerry Dunne MVB, PgCertSAS, GPCertSAS, MRCVS recount the case of a male crossbreed dog that presented with a growing mass situated under its right eye.

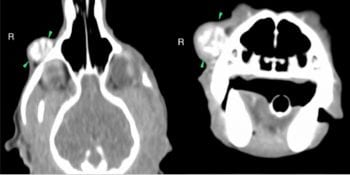

Figure 1. Note nodular mass/density in the right lower eyelid.

A patient presented with a three-month history of a mass growing in/on its right lower eyelid area. Based on fine needle aspiration and CT, a diagnosis of a parosteal sarcoma was made. Surgical treatment was planned to include removal of a section of the maxilla, and replacement of this with a 3D-printed implant and a lip-to-lid skin flap to close the defect and preserve functional lower eyelid. The procedure resulted in complete excision, excellent cosmetic repair and good functionality of the lower eyelids.

Although removal of these types of masses is not novel, the use of the 3D printed technology as an implant in combination with this skin flap is not yet commonplace.

This case report highlights the benefits of using modern technology in first and second opinion practice, and what can be accomplished with careful planning and surgical treatment. Note these surgeries should only be undertaken by someone suitably qualified or with considerable experience in eyelid/soft tissue/orthopaedic surgery.

Patch – a seven-year-old male, neutered, small crossbreed dog – was initially seen for a mass under his right eye (Figure 1).

The mass had been seen to be growing fairly rapidly, from approximately pea-sized to its current size (approximately 2cm) in around three months. Patch was otherwise unaffected by this and had no signs of ocular issues or any signs of systemic illness.

Initial diagnostic workup included a full systemic evaluation and ocular examination. Patch also had a fine needle aspiration (FNA) taken of the mass, which was sent to a specialist laboratory for interpretation.

The results of the FNA suggested the mass to be a sarcoma, although the actual origin was unclear. Indication existed that this could be of bony origin – possibly a form of osteosarcoma.

Cytology report comment was as follows: “The presence of osteoclasts and presence of rare osteoblasts suggests this mass involves the bone, despite the mobile feeling. Imaging of the mass is recommended. The morphology of the neoplastic cells may be consistent with osteblastic origin (osteosarcoma), but there is some morphologic overlap with the histiocytes seen here, and a histiocytic sarcoma is, therefore, also considered possible.”

Following the results of the FNA, the authors progressed to preform a CT scan of the head, chest and abdomen. They also performed full haematology and biochemistry blood tests, as well as urinalysis, in an attempt to help rule in, rule out or stage metastatic disease. The CT scan of the head (Figure 2) suggested the mass had mineral attenuating material centrally that was surrounded by a thin rim of soft tissue. The mass lesion was in contact with the external margin of the right maxilla (bordering zygomatic bone), but no adjacent periosteal reaction was identified.

The CT of the chest and abdomen did not show any obvious signs of metastasis. Blood tests and urinalysis also did not show any gross abnormalities of concern. The appearance of the mass lesion, the CT findings and the FNA result of sarcoma was suggestive of a parosteal osteosarcoma, which is generally regarded to have a low metastatic rate1.

The mass was in contact with the right maxilla, so clean margins would have been unlikely to be gained without at least partial maxillectomy.

After full discussion with the owners, it was decided to progress with surgical removal of the mass. The goal was to attempt to attain tumour-free margins, but plan for additional radiation therapy if needed. To gain margins, this would mean removal of an area of bone of the maxilla, and soft tissue surrounding the mass, including the lower eyelid.

With these factors in mind, the authors planned to replace the ostectomy site with a 3D-printed surgical implant of Nylon SLS that would be fixed into place or, failing this, they could use a mesh implant (Figure 3). The lower eyelid and skin defect was planned to be replaced using a lip-to-lid procedure.

The patient was anaesthetised using a standard premedication of methadone and medetomadine. We also gave perioperative antibiosis IV – namely cefuroxime – as well as meloxicam SC. Induction was with propofol.

The surgical site was prepared in routine surgical prep manner, and the oral cavity and mucous membranes on the affected side cleaned and decontaminated as much as possible. Surgical margins were determined and drawn out with surgical marker pens prior to incisions. The parotic duct opening was cannulated to allow identification of the parotid duct during dissection and so it could be avoided.

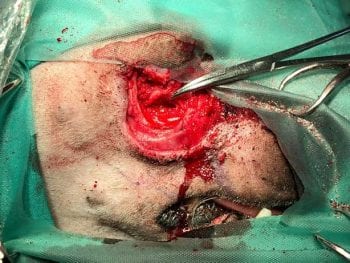

The entire lower eyelid and appropriate macroscopic normal margins were resected and removed. A section of bone was removed from the maxilla based on the CT description and degree of adhesion found intraoperatively. A section of the implant was then cut to fit the excised bone and plated in place (Figures 4 and 5).

A flap of cheek and upper lip was harvested, starting just rostral to the commissure of the right side, and with meticulous closure of the lower conjunctival margin and surrounding soft tissues, the graft was sutured in place so the mucocutaneous margin of the upper lip then became the lower eyelid (Figures 5 to 7).

The patient recovered well, but was held in hospital for 48 hours to facilitate pain control. The graft appeared healthy, although during the healing phase, two small areas at the lateral and medial canthi showed some superficial necrosis. These, however, were very superficial and not treated, but rather allowed to granulate. The eye remained comfortable throughout the healing process barr a transient conjunctivitis. This was treated with topical antibiotics and the eye was also kept on topical tear replacers.

The three-month follow-up at this point has a good cosmetic appearance, some limited movement of the lower lid (although mostly just reactive to the globe) and no signs of any local recurrence. The eyelid margin holds the tear film very well and the eye remains very comfortable (Figure 8).

Masses of the face and/or periocular area are not uncommon, although the types of masses vary in their origins and behaviour. Common masses of the periocular area and face include meibomian adenomas and adenocarcinomas (glands), melanomas, squamous cell carcinomas (skin), sarcomas, mast cell tumours and papillomas, among others. Uncommonly, one can also have inflammatory masses (also known as pseudotumors) of the eyelids2. Many eyelid-based tumours are benign and benign neoplasms outnumber malignant forms 3:1.

The difficulties with removal of neoplasms – especially invasive or malignant ones in this area – is the potential to involve underlying bone, the lack of free skin to close the defect, or involvement of mucocutaneous tissues over sensitive areas such as the eyes.

Although repair of some defects of these bones with mesh implants is probably easier, and possibly more economical for owners, the reconstruction of sections of bone with novel 3D-printed surgical implants is gaining in popularity as it provides a way to more accurately replicate the shape and form of the original bone – especially in areas such as the jaw and orbit. Using predetermined “jigs” or cutting guides to allow accurate cutting of both the implant and the bone makes this process easier and even more accurate.

Implant materials can vary from Nylon SLS (as in the authors’ case), ceramics and titanium to artificially developed calcium phosphate-based implants that mimic bone and help tissue ingrowth (these can even be impregnated with growth factors)3.

Since the eye was otherwise healthy and sighted, the authors elected to maintain the healthy eye for the patient and, therefore, it was critical to mimic or reconstruct the lower eyelid margin as well as possible. In this case, we had no choice but to completely remove the whole lower eyelid – hence the authors’ choice of brining a mucocutaneous junction of lip/haired skin into the area to replace the lower eyelid margin.

The lip-to-lid technique is well described and has the advantage that it can provide a relatively large area of mucocutaneous junction, which was ideal. This technique also offered the least likelihood of short-term and long-term complications. In easier cases, where removal of eyelid margin is up to 25% of the eyelid length (depending on laxity), these can be reconstructed using simple wedge resection and edge-to-edge suturing4.

Several surgical (blepharoplasty) procedures have been described with various degrees of success and difficulty to replace large defects in eyelids. It is worth noting the upper lid does most of the blinking over the corneal surface and is a larger lid than the lower one. The authors have mentioned a few of these blepharoplasty techniques below to compare to our chosen lip-to-lid technique.

Techniques such as the Mustardé technique that “borrow” a portion of eyelid (and eyelid margin) from the healthy eyelid to give to the unhealthy lid should, in the authors’ opinion, only be used as a last resort when “borrowing” from the upper, more mobile lid – hence the decision not to perform this technique here, for fear of compromising the health/viability of the healthy upper lid margin.

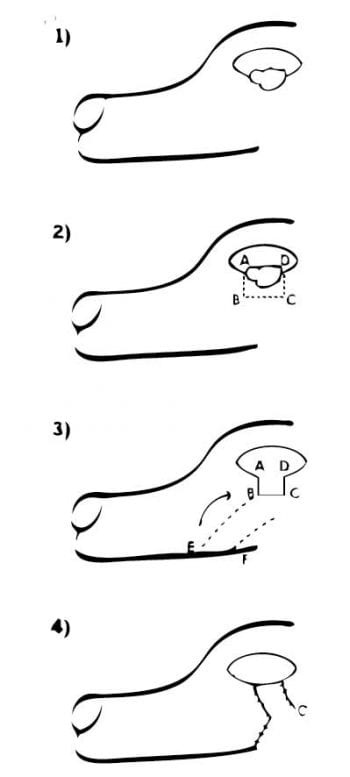

A sliding canthoplasty can be used for smaller masses where enough viable lid margin is still available to create a good surface. This involves simple mass removal, and suturing the lateral and medial remaining lid margins together. The lid is then lengthened by means of a lateral canthotomy technique (also known as the triangle-triangle or house-inverted triangle blepharoplasty).

The Roberts-Bistner procedure5 involves a pedicle of skin and orbicularis oculi being rotated into the lid defect from the heathy lid, without actually affecting the lid margin of the healthy lid. This shares the issue as with many techniques that do not include a mucocutaneous junction in the transposition, in that we risk trichiasis.

A sliding skin graft advancement flap (Figure 9) combined with a tarso-conjunctival graft is a simple sliding skin flap taken from facial skin below/above the defect. Variations of this, such as the full thickness bucket handle graft, have also been described. However, even with modifications to include conjunctiva within the flap, this technique does not bring eyelid margin into the defect and does risk trichiasis developing as a result of hair from the flap irritating the cornea.

The use of various other sliding skin and eyelid grafts – for example, z-plasty procedures and semicircular skin flaps – all have the same problem of a lack of eyelid margin.

The accurate mimicking of the original bone shape and structure of the orbit, along with the positioning of a skin/mucocutaneous margin along the corneal surface that holds tears well, has the best chance to provide favourable long-term results for the patient.

Most periocular neoplasms are benign. Using advance imaging, such as CT/MRI, will help with defining local invasion and, hence, planning of removal if one is suspicious of more than just eyelid involvement.

Use of 3D-printed implants should be considered in reconstruction of bony tissues. Understanding of the available blepharoplasty techniques can result in good cosmetic and functional reconstruction of eyelid anatomy despite removal of an entire eyelid.