3 Jan 2023

Charlotte Swanson and Matt Gurney discuss how this treatment works in cats and dogs with OA, and evidence showing improvements in quality of life.

Golden retriever © MilsiArt / Adobe Stock. Cat © 5second / Adobe Stock.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are a relatively new treatment option for pain management in dogs and cats.

Their veterinary products are licensed:

These agents are both anti-nerve growth factor (NGF) mAbs, which are licensed for the treatment of OA pain by monthly SC injection.

The specifics of each indication are:

The use of mAB therapies is not new to veterinary medicine – lokivetmab (Cytopoint, Zoetis), an mAb against canine interleukin‑31, is widely used to manage pruritus in dogs with atopic dermatitis.

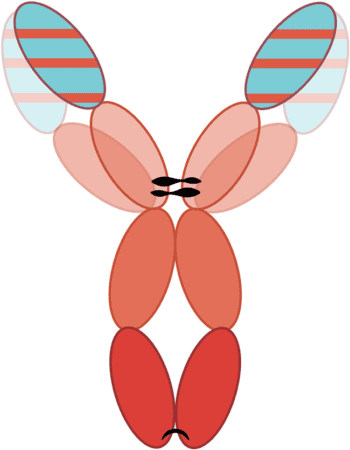

A biological treatment agent, mAbs are a homogenous population of monovalent antibodies that bind to a specific target antigen.

The complementarity‑determining regions (CDRs) within each antibody are responsible for their specificity for the target antigen.

The remainder of the antibody structure has been developed to be species‑specific, to reduce the risk of immunogenicity (Figure 1).

Although it seems obvious, It should be noted that products cannot be used in a different species.

With bedinvetmab and frunevetmab, these CDRs are specific for NGF (Enomoto et al, 2019). By binding to NGF, the mAbs prevent it from interacting with its receptor, tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA), and blocking the downstream effects – transmission of the painful stimulus.

NGF is a proinflammatory neurotrophin that is important for normal neuronal development in the fetus and neonate.

In adults, NGF is involved in acute and chronic pain (Mantyh et al, 2011). It is released by damaged synovial cells and chondrocytes – elevated levels of NGF have been found in the synovial fluid of dogs with naturally occurring OA.

Expression of NGF and its receptor, TrkA, increases with elevated severity of synovitis (Yamazaki et al, 2021).

NGF is released from damaged tissue. NGF binds to TrkA receptors on peripheral nociceptors within the joint, forming receptor complexes that are transported to the dorsal root ganglion, the cell body of the primary afferent.

The NGF:TrkA complex formed at peripheral nerve terminals is carried by retrograde transport to the neuronal cell body in the dorsal root ganglion, where the synthesis of peptides and ion channels involved in pain transmission is upregulated – leading to increased levels of both receptors and neurotransmitters at the nociceptor.

This results in both rapid onset (using established transmission mechanisms) and delayed effects as a result of gene upregulation. Local modulation of receptors and ion channels at the peripheral nociceptor terminal is an immediate effect. Transcriptional changes leading to increased peptide and ion channel synthesis, followed by anterograde transport to peripheral and central terminals, is a delayed effect.

These actions increase neurotransmission in the primary afferent nerve, increasing activity at the dorsal horns of the spinal cord.

If activity at the dorsal horns is intense, or persistent, central sensitisation can develop.

Mast cells play a role in peripheral sensitisation. NGF released from damaged tissues binds to TrkA receptors located on mast cells. This triggers a positive feedback that causes further release of NGF.

The activated mast cell triggers a whole host of inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins, bradykinin and histamine, which further sensitise the nociceptor and reduce its threshold for firing.

By targeting levels of NGF with anti-NGF agents, inflammation reduces.

Central sensitisation is a consequence of OA, and can be seen clinically as allodynia and hyperalgesia. The role of NGF in central sensitisation is well established, and involves binding of glutamate to the N‑methyl‑D‑aspartate receptor and binding of brain-derived neurotrophic factor to the tropomyosin receptor kinase B receptor (Enomoto et al, 2019).

Allodynia is a painful response to a non‑noxious stimulus (for example, light touch) and hyperalgesia is an increased response to a painful stimulus (for example, marked pain from manipulation of an arthritic joint). Both of these characteristics can be noted on physical examination.

The first step in treating central sensitisation is to reduce the peripheral input – and anti‑NGF agents play a key role here.

The transport of the NGF:TrkA complex to the dorsal root ganglia triggers a phenomenon known as neurogenic inflammation (Fox, 2009), whereby new inflammatory mediators are produced and transported back to the peripheral terminal of the nociceptor. This triggers further activity and pain transmission in that nerve. This is a key area to target – and anti-NGF drugs are valuable resources.

To date, no studies directly compare the use of anti‑NGF products to NSAIDs in either dogs or cats.

The onset of action of both products is anecdotally reported by owners to be within days of injection. The first assessment time point in dogs for Librela was 7 days, and for cats with Solensia was 28 days.

In licensing studies, both products were administered at monthly intervals. A longer duration of effect has not been documented.

The advantages of using mAbs include:

Bedinvetmab and frunevetmab are suitable first‑line treatment options for OA in dogs (bedinvetmab) and cats (frunevetmab).

These products represent advances in the veterinary field of pain management, and offer veterinary professionals an excellent new resource for improving quality of life in dogs and cats suffering with the chronic pain of OA.