29 Jan 2018

Tim Hutchinson details causes, assessment and management of degenerative joint disease to help both pet owners and practice staff better understand this disease.

The majority of canine patients will develop OA in one or more joints during their lives. However, OA is often poorly understood by pet owners and practice staff alike, resulting in many patients remaining undiagnosed, or looked on simply as “getting old”.

Raising awareness of OA will benefit many patients – especially as management of these cases often involves the whole practice team.

OA (also known as degenerative joint disease) can be defined as the decreased function of synovial joints due to the progressive destruction of articular cartilage, accompanied by deposition and remodelling of periarticular bone, with fibrosis of surrounding soft tissues. Superimposition of inflammation is the result of the disorder and perpetuates the destructive changes.

The inciting cause of OA is damage to the articular cartilage, which triggers a vicious circle of degenerative changes and inflammation.

Joints are formed by the junction of two articulating bones; the end of each bone is covered by a specialised type of smooth and hard-wearing articular cartilage, and allows the bones to articulate with minimal friction. Its dense, compressive structure also gives it excellent shock-absorbing characteristics.

Given the underlying cause of OA is damage to the articular cartilage, OA may be initiated when the rate of damage exceeds the rate of repair. It may be useful to consider how OA might be classified.

Very crudely, an arthritic patient may arise for one of four reasons.

Normal wear and tear damage to the joint surfaces, but that, over time, exceed the body’s capacity for repair and trigger the onset of OA. This is essentially an old age problem of humans, not dogs.

Abnormal loading of a normal joint can occur for two common reasons in our patients:

Normal loading of an abnormal joint is common in vet patients due to the myriad of developmental disorders that exist in certain popular breeds. These cause an incongruence between the joint surfaces, resulting in the force being focused on a small area of the joint.

Abnormal loading of an abnormal joint is the most common scenario and is the result of combining abnormal loading of a normal joint with normal loading of an abnormal joint.

Because cartilage has a limited capacity for repair, once it is damaged, any repair will take place very slowly. Due to the lack of innervation to the cartilage, the pet will be unaware and will further exacerbate the damage by continued weight-bearing.

While it may be necessary to rule out other conditions that mimic OA (such as neoplasia, sepsis or fracture), diagnosis of OA is often relatively easy.

The cardinal signs of morning stiffness, easing during the day and stiffening up again in the evening, are familiar to us all. However, many owners will attribute this to their pet “getting old”. This results in many cases of OA not being identified until the disease is quite advanced and secondary changes, such as muscle atrophy and chronic pain, have set in.

OA is not a static condition, and the clinical signs will wax and wane in line with the overall inflammation. However, the underlying pathological changes will continue to deteriorate. On palpation, you will be able to identify which phase the patient is in.

For example, during the acute inflammatory phase, the joints may feel swollen and warm, and may be painful when you apply pressure. Conversely, once the inflammation has subsided, you will be able to palpate the knobbly periarticular bone changes and note less discomfort on pressure. While palpating the joints, it is also important to pay attention to specific areas of discomfort and assess the musculature status, noting muscle tone, asymmetry, whether whole groups or individual muscles are affected and the girth of the limb.

Joint manipulation will yield information relating to the range of motion, resistance to movement and level of pain invoked. Note, the degree of crepitus in the joint correlates poorly with the clinical severity of the condition.

Radiography is useful for confirming presence of OA. It may give an indication as to the severity of the whole pathological picture. However, it is a poor correlator with the clinical picture, prompting the maxim: “Always treat the animal, not the radiograph.” By the time radiographic changes to the bones are present, significant and irreparable damage to the articular cartilage will have occurred (Figure 2).

Occasionally, it might be useful to obtain a sample of synovial fluid, to rule out joint sepsis or immune-mediated arthritis.

It is imperative clients realise OA is a condition to be managed, not cured, and treatment will be lifelong and involve lifestyle changes. It is vital the “Holy Trinity” of OA treatment is put in place first before exploring other adjunctive therapies, and includes the following.

Pain control will principally be achieved by using NSAIDs, although, in addition, other medicine classes will be required when central sensitisation is present.

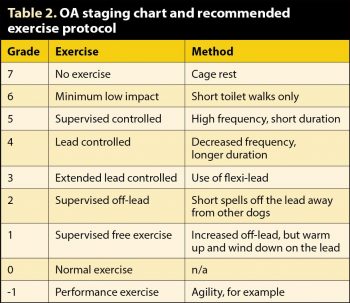

In general, exercise is good for arthritic joints. However, it is the type of exercise that is important. Regular, gentle lead walking will ensure controlled load-bearing via an appropriate range of motion. Off-lead, sudden, stop-start, chasing exercises will lead to increased shear action on joints and stress to the extremities of the ranges of motion.

Owners need to understand this because OA is not a static condition and the exercise needs will vary according to the clinical stage of the disease. Using Table 2 may help explain this and manage your client’s expectations.

The chief barrier regarding the ability to both modify and control exercise is that it becomes a lifestyle change for the client.

Excess weight increases the load on damaged joints and, coupled with the shearing forces resulting from inappropriate exercise, can be hugely detrimental. Most OA patients will have undergone a degree of muscle atrophy due to pain and inactivity, and will lack muscle support. Appropriate exercise, nutritional balance and physiotherapy is required to start addressing requirements for weight control and body condition.

Many clients will be innocently unconscious of the ideal body condition for their dog.

Several adjunctive therapies may be considered once the “Holy Trinity” is in place. Physiotherapy and hydrotherapy can help support and restore muscle quality, while less well understood and yet-to-be proven therapies are chiropractic and nutraceuticals. Making changes to a dog’s environment is also beneficial – installing ramps to avoid steps or help it get into a car, and using rubber matting on slippery floors, can help improve the patient’s mobility and comfort at home.

OA is a progressive condition we need to educate our clients can be managed, but not cured. Be realistic and manage expectations about the level of recovery we can expect from a patient. To aid compliance, it is vital owners understand the impact weight management and controlled exercise can have on OA progression. When diagnosing OA, never judge a patient by its radiograph alone. Always get your “Holy Trinity” in place before introducing adjunctive therapies. Take a good history and make accurate recordings of your findings on physical examination and observation.