11 Oct 2022

Stephanie Hedges BSc(Hons), RVN, CCAB explains how the lockdowns have impacted young dogs’ socialisation skills and how this can be rectified.

The pandemic might not be having such a direct impact on our day-to-day lives anymore. However, its legacy is still being felt in many ways – including the long-term impact it has had on the behaviour of our dogs.

One of the few upsides of what felt like never-ending lockdowns was that many dogs weren’t left alone as much as they would normally be. Our need to rapidly adapt to working from home has also made this possible in the longer-term for many people. However, many more have needed to go back to work. Older dogs that had habituated to this before coronavirus turned our lives upside down are mostly likely to have soon settled back into the old routine. However, being separated from their social group isn’t natural for dogs, and so is something they have to get used to gradually – preferably starting from an early age. Puppies that didn’t have the opportunity to do this – especially those that have a generally anxious temperament – may now be struggling when suddenly left alone.

Lockdowns also restricted opportunities for social interaction and for learning about the world – both for puppies born during the pandemic and those born in the year leading up to it.

Puppies are at their most sensitive to developing social bonds, learning about life and learning how to cope with novelty during their first 13 weeks of life, so early lockdown puppies may now be showing fear in a variety of situations.

However, opportunities for social interaction and confidence-building need to continue throughout a puppy’s first year for it to grow into a well-balanced dog. Puppies born in 2019 may be showing this type of behaviour, too.

One of the most common negative effects of the restrictions on socialisation being seen is poor social skills around other dogs. Puppies learn how to greet, play and resolve disputes with other dogs through repeated social interactions throughout puppyhood.

However, most owners were reluctant to allow their puppies to approach and mix with other dogs, due to the fear of fomite and zoonotic transmission in the early days of the pandemic. Classes were also initially suspended, and later either online or “socially distanced”. This prevented normal greeting and structured play sessions. We, therefore, now have a generation of young dogs with poor social skills that can manifest as fearful, frustrated or simply rude behaviour around others.

Another common effect is fear of strangers. This may be people met outside of the house – again, due to owners being reluctant to allow their puppy to approach or be touched by people on walks – but is more commonly towards visitors or when visiting the practice. The restrictions on meeting indoors meant most people had few or no visitors for many months, or even years, so their puppies didn’t learn to accept unfamiliar people coming into the house.

Practices also postponed puppy vaccinations and limited physical examination wherever possible for a long time, and when they did examine puppies, they usually took them away from owners, which is known to make them more fearful.

Practices also suspended non-essential services, such as nurse-led social visits and puppy socialisation classes. Early experiences of the practice were, therefore, less likely to be positive and unavoidable interventions were unlikely to be balanced with more fun experiences.

But all is not lost. The key things a puppy needs to learn during its first few months is which species it is, that people are its friends and how to cope with a variety of new things in a proportionate way.

Although the pandemic limited this, in most cases, puppies will have met other dogs via their dam and siblings, and people via their owners, and so have developed social bonds with the species that matter.

They were also able to be walked, and so experience life, albeit much quieter than normal. They, therefore, still had the key experiences they needed at the most important time.

Owners can then build on this, with help from an animal training instructor (ATI), clinical animal behaviourist (CAB) or veterinary behaviourist (VB), depending on the severity of the problem. Addressing mild wariness or unwanted behaviour, rooted in a lack of training or poor manners, can usually be supported by attending well-run training classes, or a 1-2-1 with an ATI.

More severe behaviour and any behaviour involving aggression will require input from a CAB or VB.

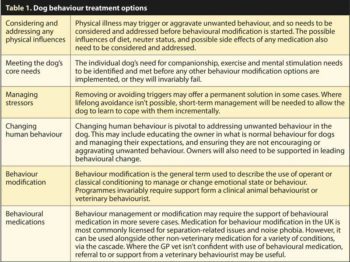

A VB is particularly useful where comorbidity exists with medical and behavioural problems, or where behavioural medication is needed and the GP vet isn’t familiar with prescribing this. Treatment options are summarised in Table 1.