4 May 2022

Simon Tappin MA, VetMB CertSAM, DipECVIM-CA, FRCVS raises awareness of some of the most common diseases threatening UK animals travelling in Europe.

Image: © Lightspruch / Adobe Stock

As the pandemic eases, pet travel is going to increase as we start to get on with our lives again. Some slight changes for travel post-Brexit have occurred, but the basis of the Pet Travel Scheme remains and has been extremely successful in its goals, which were primarily to protect people in the UK from rabies and Echinococcus multilocularis.

However, significant risks exist to individual animals from exposure to diseases that are not currently endemic in the UK. Diseases such as Babesia, Ehrlichia, Leishmania, Brucella and Dirofilaria are all present within mainland Europe, with evidence suggesting naive, non-native animals may be at increased risk of developing severe disease.

It is important firstly that owners recognise these risks prior to travel and take appropriate precautions to minimise exposure, but secondly, that the veterinary profession is aware of these non-endemic diseases so prompt and appropriate treatment can be administered.

Since the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS) was introduced in 2000, travelling to and from the UK without the need for a six-month quarantine period has become the norm.

Prior to Brexit, PETS allowed relatively free travel within qualifying countries once the PETS criteria have been met.

Post-Brexit, the basis of the scheme remains, with the UK having part 2 listed status.

Since 1 January 2021, requirements for travel to the EU include the use of a certificate rather than a pet passport; a microchip; rabies vaccination at least 21 days prior to travel; that dogs must be treated against tapeworm 24 to 120 hours before arriving if travelling to a tapeworm-free country; and an animal health certificate, no more than 10 days before travel.

The primary aim of PETS was to reduce the risk of importing rabies and the zoonotic tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis, both of which are not currently endemic within the UK.

While the scheme allows convenient travel, it does not contain statutory requirements to reduce the risks of “exotic” disease and, as a result, an increasing number of clinical cases are being encountered within the UK.

Quarantine requirements were introduced in the UK in 1897 to primarily control rabies. Rabies is still an important zoonotic disease as, once clinical signs develop, it is invariably fatal and currently kills approximately 55,000 people each year, mostly in Asia and Africa.

Rabies has an incubation period of two to three months, meaning that initially infected animals appear normal. Quarantine was, therefore, designed to hold imported animals in a secure area to see if clinical signs develop.

The six-month period of quarantine is longer than the incubation period and ensures that if an animal is infected with rabies, its clinical signs are seen without the risk of rabies being spread throughout the country. This approach allowed the UK to become rabies free in 1922, with the last endogenous case of classical human rabies recorded in 1902.

In Europe, the main reservoir for infection comes from the fox population; however, over the past three decades oral vaccine-laden bait programmes targeted at foxes and raccoon dogs have been very successful in reducing the incidence of rabies in several western European countries.

As a result, many countries became rabies free, but subsequent importation of rabies-infected dogs has threatened both France and Italy’s rabies-free status, highlighting the need for continued vigilance.

PETS insisted on animals being vaccinated against rabies, which further reduces the risks of animals bringing rabies into the UK.

Vaccines give extremely good protection from rabies and although occasional vaccine failure is reported, this becoming a significant risk was deemed very low, leading to the relaxation of the need for the documentation of the six-month post-vaccination titre.

The current scheme also required that dogs are wormed with praziquantel or equivalent 24 to 120 hours prior to returning to the UK, which is designed to stop the tapeworm E multilocularis entering the country.

E multilocularis is more commonly known as the fox tapeworm and is endemic in many parts of the world, including northern and central Europe. Its life cycle involves foxes and small herbivores, such as voles. However, dogs and cats can also be infected.

Although E multilocularis is of little clinical consequence to animals, aberrant infections in humans results in alveolar echinococcosis, which is an extremely debilitating disease with a high mortality rate.

People become infected with E multilocularis by ingesting eggs that are excreted by infected foxes, dogs or cats. These develop into the larval stage and initially form small cysts within the liver. However, over time (usually between 5 and 15 years) the cysts enlarge leading to clinical signs such as jaundice, abdominal pain and weight loss. If left untreated, this disease can be fatal.

It is important for owners to realise that pet travel arrangements are primarily focused at stopping imported zoonotic diseases entering the UK. No statutory provision exists to reduce the likelihood of animals being exposed to diseases that are currently not endemic within the UK.

The area to which the animal has travelled largely dictates the diseases that will be important risks; for example, travel around the Mediterranean basin leading to potential exposure to mosquitoes carrying Dirofilaria (heartworm) and travel to the US possibly leading to exposure to fungal diseases such as blastomycosis.

The main diseases encountered in mainland Europe include Babesia, Leishmania, ehrlichiosis and dirofilariasis.

Babesia is a tick-borne disease that can cause severe and life-threatening anaemia in dogs.

It is particularly prevalent in France, with increasing incidence in the south (particularly south of the Loire Valley), although tick vectors are widespread and the disease in endemic in most of mainland Europe. High levels of Babesia sporozoites within tick saliva are passed into the host’s circulation when the tick feeds; it must feed for a minimum of 48 to 72 hours for transmission to occur.

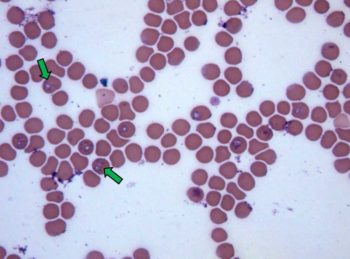

The life cycle is continued in the host by the production of merozoites within erythrocytes (Figure 1). These either infect further erythrocytes or the life cycle is completed by infecting ticks during feeding.

Babesia infection results in an array of clinical signs that vary between the strains present. Most signs result from haemolytic anaemia or the systemic inflammatory response this generates, and multiple organ failure can result.

Diagnosis of canine Babesia is most convincingly made by demonstrating the presence of organisms within infected erythrocytes, with Babesia canis usually forming pairs of pyriform organisms. The level of parasitism is often low, especially in chronic cases, which can make detection difficult.

Collecting blood from peripheral capillary beds (for example, the ear tip or nail bed) can yield a higher number of infected cells. PCR is the most sensitive and specific way of diagnosing infection, and also allows determination of the species present.

Treatment for babesiosis relies on parasite clearance and supportive care. In general, imidocarb (two doses of 6.6mg/kg IM given at a 14-day interval) is suggested as the most effective drug for parasite clearance and improvement is normally seen within 24 hours of treatment.

Clindamycin is suggested until definitive treatment is available (25mg/kg every 12 hours). Supportive care usually consists of IV fluid therapy, and symptomatic treatment of clinical signs such as vomiting and diarrhoea. In cases of severe haemolytic anaemia, oxygen therapy and blood transfusions can be required.

Babesia is carried by Dermacentor reticulatus (Figure 2) and Rhipicephalus sanguineus (the brown dog tick). Although D reticulatus is present within the UK, it is not thought to harbour Babesia.

This raises the concerns that Babesia could become established in the endogenous tick population and climate changes could favour proliferation of suitable vectors.

Worryingly, several cases of Babesia were reported in the Harlow and Romford areas of Essex in 2015-16, although more recent cases have not been reported.

Leishmania is carried by the sandfly, which limits cases of infection to the area around the Mediterranean basin. Currently, sandfly does not live in the UK as the climate is too cool, although with climate change it is possible the vector may spread into southern England.

Leishmania is a zoonotic disease, with dogs being an important reservoir for human infection. The risk of zoonotic infection is low; however, children or the immune suppressed are potentially susceptible.

Mechanical transmission is also possible from dog to dog and dog to man. Infection in this way is rare, but occasional cases of Leishmania are being reported in non-travelled dogs co-housed with a travelled animal.

When the sandfly feeds, flagellated Leishmania promastigotes are injected into the animal. These are engulfed by macrophages and become disseminated in the body. A long incubation period then follows (ranging from a month to many years) before amastigotes develop and lead to clinical signs.

Cats seem much more resilient to infection compared with dogs, but clinical disease is rarely reported.

Classic signs of Leishmania follow a very chronic course, with clinical signs including weight loss, lymphadenopathy, lameness and exfoliative dermatitis.

Due to chronic immune system stimulation, polyclonal gammopathies are often seen. Proteinuria secondary to glomerulonephritis is also commonly reported.

Diagnosis can be made on visual identification of the parasite in lymph nodes or bone marrow. If organisms are not visible then PCR is a more sensitive test, with lymph node samples and bone marrow being the best samples to submit.

Treatment for Leishmania is protracted and of variable success. Allopurinol is usually used in combination with meglumine antimoniate or miltefosine. Neither of these drugs is licensed for use in the UK, thus a special import certificate is needed from the VMD.

Supportive treatment for renal dysfunction and secondary bacterial pyoderma may also be needed.

Domperidone can also be useful to help control chronic infection; administration helps promote an intracellular immune response to the intra-cellular organism, rather than a less effective and potentially detrimental antibody-based response.

Ehrlichia canis is a tick-borne intracellular rickettsial parasite found in southern Europe and the Mediterranean basin.

Ehrlichia is transmitted by the brown dog tick and disease mirrors the prevalence of this vector. Although Ehrlichia is not currently endemic in the UK, if R sanguineus becomes more prevalent, a potential disease reservoir would be created.

Once infected, three phases of ehrlichiosis are seen: acute, subclinical and chronic. The acute phase has an incubation period of 8 to 20 days and consists of non-specific signs such as fever, anorexia and lymphadenomegaly.

Dogs usually recover spontaneously before entering a period of subclinical infection. Some dogs clear the organism at this stage; however, in some dogs the organism persists, leading to chronic infection.

Chronic infection leads to leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction, leading to severe bleeding in some cases (submucosal haemorrhage and epistaxis).

Diagnosis can be made on the basis of PCR or finding the Ehrlichia morulae in leukocytes, although this can be difficult and time consuming.

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice (5mg/kg twice daily or 10mg daily for 14 to 21 days); however, imidocarb can be useful in resistant infection.

Adult Dirofilaria immitis are true heartworms and reside in the pulmonary arteries and the right ventricle, and usually lead to little obstruction to the vasculature.

These worms produce microfilariae that are released into the bloodstream. Microfilariae are ingested by mosquitoes in which development to the L3 larval stage occurs; this is infectious when the mosquito feeds.

These migrate to the pulmonary arteries and mature to adults, moving to the right ventricle at this stage. If both sexes are present, microfilariae are produced six to seven months after exposure.

The dog is the primary host for D immitis and zoonotic infections are rare.

Currently, D immitis is not endemic in the UK; however, it is widespread through most of North America and southern Europe.

Native mosquito vectors have been shown to be able to transmit the L3 larvae in laboratory conditions. Outside the laboratory, however, ambient temperatures are not warm enough for larval development, preventing heartworm becoming established.

Most infected dogs have few clinical signs; however, disease comes from pulmonary arterial disease. Irritation to the pulmonary endothelium leads to pulmonary thromboembolism and hypertension, causing signs such as coughing, dyspnoea and exercise intolerance. The severity of these signs depends on the number of worms present, the duration of infection and the host immune response.

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and demonstrating the presence of microfilariae, which can be seen on blood films or documenting the presence of antigen.

Treatment of adult infections is not without risk, as dead worms will be swept into the pulmonary tree. Vascular removal is a possible alternative.

Preventing infection with chemoprophylaxis is, therefore, a much better strategy, with monthly milbemycin or selamectin having proven efficacy.

Although PETS has worked well for the UK in preventing the importation of non-endemic zoonotic diseases, it is important for vets in the UK to remain vigilant to the risks of imported disease and to provide accurate information to clients regarding the risks associated with overseas travel.

Depending on the area visited, heartworm prophylaxis may be needed; insect repellent collars and limiting exposure to flying insects at dusk and dawn may reduce exposure to diseases like Leishmania; and acaricides and tick removal may limit the transmission of diseases such as Babesia and Ehrlichia.

Some of the drugs in this article are used under the cascade.