23 Sept 2019

Kelly Bowlt Blacklock discusses this topic in dogs and cats, including attitudes towards pain and how to reliably assess patient pain levels.

Treatment of pain should be a mandatory part of good veterinary practice. In human medicine, self-reporting of pain levels is considered by many to be the gold standard in pain management. This luxury is not available in veterinary medicine, making adequate assessment of pain levels in our patients challenging.

This article examines our attitudes towards postoperative pain, how we can reliably assess patient pain levels and how the surgeon may contribute towards improved postoperative comfort.

Pain is a complex, subjective and emotive experience, generated following activation of the nociceptive system1. Pain is naturally occurring for protective purposes (for example, against potentially dangerous stimuli), but is also associated with surgical and medical conditions.

It is well-recognised and scientifically proven animals perceive pain2; therefore, treatment of pain should be a mandatory part of good veterinary practice, and this requires the ability to recognise pain and assess its intensity.

Female vets and newer graduates usually record higher postoperative pain scores, and are much more likely to administer analgesics than male and more senior counterparts, respectively3-7.

Vets are also more likely to administer analgesics to dogs than cats, despite both species having undergone the same procedure8.

Interestingly, the attitude and response to small animal pain management varies considerably between countries and veterinary professionals, highlighting valuable areas for improvement within the profession. Some examples include:

The ability to self-report is usually considered the gold standard in pain management in humans13. In companion animals, this is not possible. Additionally, almost all animal species hide the presence of pain because any perceived weakness may be disadvantageous to its survival1. Various strategies have been proposed to facilitate the recognition of postoperative pain and should be used in combination wherever possible1.

As in humans, the level of pain perceived by our patients is usually proportional to the extent of surgical and/or pathological damage14.

Previous authors have listed examples of anticipated pain levels associated with surgical procedures1 and the use of presumptive scoring usually leads to a proportional level of appropriate pain therapy14; however, the clinician/nurse should be mindful the experience of the individual patient may modify his/her pain intensity (for example, pain threshold, previous painful experiences, signalment and so on), and allowances should be made for this.

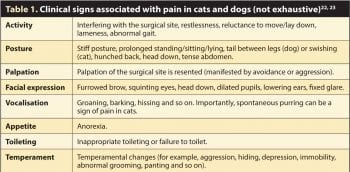

Assessment of psychomotor changes and pain expressions can aid in the detection of pain in almost all animals, including reptiles and birds (Figures 1a to 1d)14-18. Indeed, facial expressions of pain are the most commonly used indicators of procedural pain in infants and young children due to their objectivity, universality, accessibility, sensitivity and specificity, being first systematically described by Charles Darwin in 187219-21.

Standardised pain scales have many advantages; they allow the clinician to attribute an objective pain score to a patient, provide a repeatable measure that is consistent between users, direct the operator to an appropriate therapy and allow objective evaluation of a patient’s response to management.

In the UK, only 8.1% of surveyed veterinary practices use a formal pain scoring system, but 80.3% of nurses agree this is a useful clinical tool12.

Many pain scales have been drawn up, most of them extrapolated from human experience. They include:

Visual analogue scale (VAS): a horizontal line 100mm in length, with 0mm representing no pain and 100mm the worst pain imaginable. The observer marks the line according to their interpretation of the animal’s clinical signs of pain and this can be quantified by measuring the distance from 0mm. While simple, the disadvantage of this technique is the operator requires training in pain behaviours and significant interobserver variability exists, limiting its usefulness in a team or practice scenario24, 25. Additionally, cut-off values for the administration are arbitrarily determined. A numerical rating scale (0-10) is similar to a VAS.

Simple descriptive scales: are adapted from human medicine for veterinary patients and include multiple descriptors to assess acute pain. Colorado State University have formulated excellent acute pain scales for dogs and cats, which are readily available online and easy to use26, 27.

Multidimensional composite pain scales: consider the emotional effects of pain, as well as assessing the physical pain intensity, weighing each contributor differently, which minimises the interobserver variability seen with more basic scales. The short form of the Glasgow composite measure pain scale is the best example of a composite pain scale and is the version routinely used at the AHT, where surgical patients undergo regular postoperative pain score assessment. The form is accessible and downloadable via the internet28, 29.

It is important pain scales are validated to ensure reliability and repeatability across patients and users30, 31, and only a limited number of validated pain scales are available for use in veterinary patients.

For dogs and cats, the Glasgow composite measure pain scale has been validated for assessment of acute pain and, in cats, the Sao Paulo State University Botucatu multidimensional composite pain scale has been validated for pain assessment following ovariohysterectomy22, 30, 32 (note different validated pain scales exist for canine chronic pain)33-35.

The most effective marker for the diagnosis of pain is response to analgesic treatment14. The description of drugs available to manage postoperative pain is a regular feature in Veterinary Times, and several comprehensive and elegant articles have been penned on the subject36-39. The author encourages practitioners to access these articles for further information about pharmacological therapeutic options for pain control.

Regardless of the choice of analgesic drug used, it is imperative for the clinician to understand effective postoperative pain management requires pre-emptive and multimodal analgesia. Additionally, conventional pharmacological analgesia should be augmented by a whole-patient holistic approach, including decreasing stress, warm/cold compresses, nutritional support, opportunities to toilet, facilitating sleep, frequent turning, massage, grooming, acupuncture and general tender loving care14, 37.

Importantly, regular pain assessment is crucial to assess both the baseline pain levels and response to therapy.

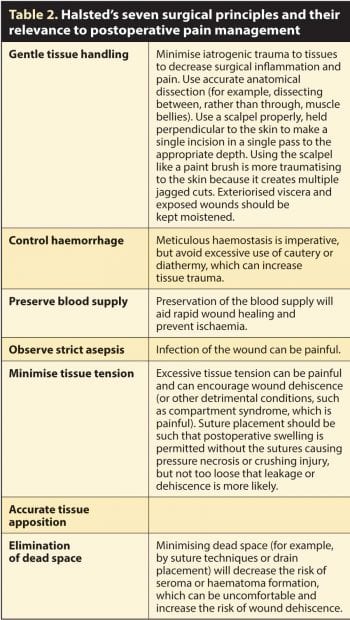

The key to reducing postoperative pain is to minimise the surgical insult that incites the pain in the first place. Halsted’s fundamental surgical principles are more than a century old, but are just as relevant today in all species and many of them are directly relevant to postoperative pain management (Table 2).

Additional surgical principles that we might add to Halsted’s principles to minimise postoperative pain include:

Avoiding surgery. This is an obvious way to avoid postoperative pain and it is always worth considering whether surgery is indicated in the first place. For example, can diagnostic gastrointestinal biopsies be obtained endoscopically; therefore, avoiding the need for an open abdominal approach?

Make the incision large enough for the job at hand. This is an important concept; forceful retraction of a wound that is too small encourages pressure on adjacent muscles, joints and nerves, resulting in tissue damage, inflammation, necrosis and pain40. Educating owners to expect a wound of an appropriate size is imperative and will remove pressure on the surgeon to attempt to create an inappropriately small wound solely for cosmetic purposes.

Consider your approach. Due consideration should be given to the surgical approach itself, and the least invasive approach selected wherever it is appropriate to do so. For example, approach to the abdominal cavity via a flank approach is associated with greater postoperative pain, compared to a ventral midline approach41. Likewise, a patient undergoing median sternotomy may require more postoperative analgesia, compared with those undergoing lateral thoracotomy, and the analgesic requirements of patients undergoing lateral thoracotomy can be decreased further by using a muscle-sparing technique42. Minimally invasive surgery is usually associated with decreased postoperative pain, compared with a traditional approach for a variety of conditions, including laparoscopic ovariectomy and thoracoscopic pericardiectomy43, 44. Minimally invasive approaches are still painful; however, insufflation and the use of carbon dioxide is associated with painful peritoneal stretching and diaphragmatic irritation respectively; therefore, it is imperative all gases are evacuated from the abdomen after the procedure and due consideration is given to intra-abdominal local anaesthesia45.

Removing drains once they are no longer required. The use of drains, where indicated (for example, to address dead space or to drain the thoracic cavity), should be wholly encouraged; however, their use is associated with tissue irritation. For example, thoracostomy tubes are associated with pleural irritation40 and pain from nerve impingement46 (along with other potential complications), and the pain associated with a larger bore tube (for example, a trochar drain) is greater, compared with a small bore wire-guided tube (for example, a MILA chest drain) in both dogs and humans47, 48. Removal of a redundant drain can provide relief from drain-associated pain.

Using local anaesthetic techniques. A variety of simple and quick local analgesic techniques exist that can be used intraoperatively to improve postoperative pain management, including nerve blocks, intra-articular and intercostal analgesia, and/or IV regional analgesia – all of which have been beautifully described elsewhere49.

The author uses topical analgesia for all surgical procedures, wherever possible. Traditionally, the application of local anaesthetics into the surgical site was avoided because of perceived tissue oedema and impaired wound healing, but this is not recognised with newer agents (for example, bupivacaine and ropivacaine).

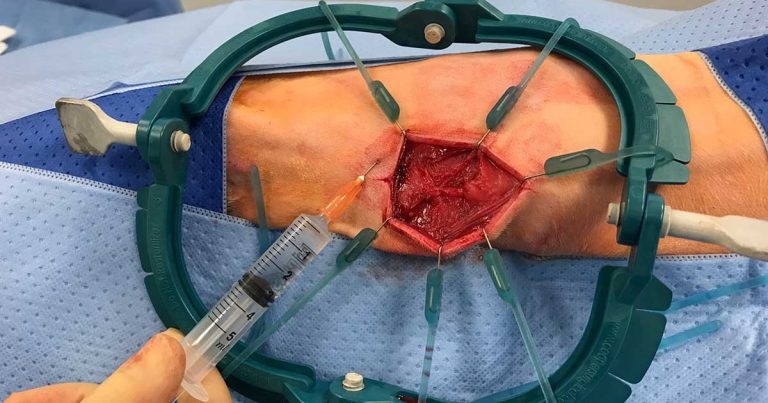

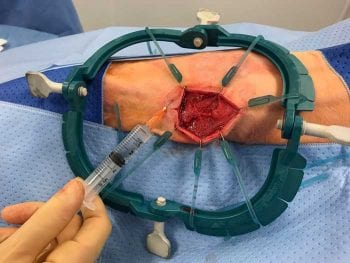

Local anaesthetics can be splashed on to the surgical site or instilled in/around the area (Figure 2) and have resulted in lower postoperative pain scores than those in a control group, with no adverse side effects50. Repeated instillation can continue postoperatively if a wound soaker catheter is placed (Figure 3).

Where chest drains are placed, intrapleural analgesia is commonly used and involves instilling a long-acting local anaesthetic (for example, bupivacaine or ropivacaine 1.5mg/kg to 2mg/kg) into the drain every six hours in an aseptic fashion.

The chest drain is flushed with sterile saline and the patient positioned with the wound at the most dependent aspect for 10 minutes (that is, patients with a median sternotomy incision are encouraged to sit in sternal recumbency, whereas those with a unilateral thoracotomy are placed with the affected side down).

This technique is easy to perform and well tolerated in conscious patients; however, systemic absorption of local anaesthetics can be higher, compared with an intercostal nerve block and may manifest as Horner’s syndrome or, rarely, phrenic nerve paralysis49.

For all surgical patients, it is imperative appropriate analgesia is provided in the postoperative period for welfare and ethical reasons, and to ensure rapid return to normal function. To achieve this, the surgeon can contribute significantly by considering the surgical technique/approach.

Postoperatively, regular pain assessment is crucial to assess both the animal’s baseline pain and its response to therapy, and the author would encourage all practices to download and use one or more of the available free pain scoring systems referenced in this article.