4 Jun 2024

Laura Watson and Ellen Marcinkiewicz discuss vaccines and parasite treatments for cats kept inside.

Image © kayeela / Adobe Stock

In the UK, a rapidly increasing number of owners and caregivers are choosing to keep their cats indoors, with the latest figures suggesting 37% of pet cats are indoor only1. As urbanisation increases, it is reasonable to assume this trend will only increase.

An indoor-only lifestyle for a cat is often chosen by an owner, mainly due to fears for their cat’s health and welfare (for example, exposure to viruses or risk of road traffic accidents), but also out of concern for local wildlife or limited access to a safe outdoor space (for example, owners living in high-rise flats).

It is important to ensure that, although owners feel their cats are physically safer being kept indoors, preventive health care is still essential, and risk factors they might not have considered can still affect their cat’s health and well-being.

Although it is considered by some owners and caregivers that indoor-only cats are not at risk of exposure to infectious diseases, because they do not have access to the outside world, it is important to advise that people can bring pathogens inside on their clothing, footwear and shopping bags, for example.

Despite the success of vaccination, all the diseases that are commonly vaccinated against are still present in cat populations; therefore, a failure to maintain routine vaccination will place cats at increased risk of contracting disease. Only around one-third of the pet cat population in the UK is regularly vaccinated1, and much wider use of vaccination would likely be of benefit, both to individual cats and to the feline population at large, in further reducing the prevalence and severity of infectious diseases.

When implementing vaccination protocols, the lifestyle of the cat and risk factors for disease need to be carefully considered; for example, indoor-only cats in a single-cat household will have no appreciable risk of exposure to feline leukaemia virus (FeLV).

However, it is important to discuss with the owner what their definition of indoor only means, as some owners might allow their cats access to an outdoor area while supervised, or the cat might have access to an outdoor enclosed pen or “catio”, where they might still have contact with other cats (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An indoor-only cat with access to an enclosed “catio” outside. Image © kayeela / Adobe Stock

The WSAVA guidelines consider feline vaccines as either “core” or “non-core”. Core vaccines protect against severe, potentially life-threatening diseases for which routine use can be justified in all cats.

The core vaccines for pet cats include the following2,3.

● Feline panleukopenia virus (feline parvovirus, FPV) – indoor cat owners need to be aware of indirect spread via environmental contamination or fomites (for example, clothing, footwear, food bowls and grooming equipment).

● Feline calicivirus (FCV) – fomite and environmental contamination is a possible mode of transmission for indoor cats, and the virus can survive for up to a month in the environment (although, the usual survival time is one to two weeks).

● Feline herpes virus (FHV-1) – with this fragile virus, environmental contamination is less likely, but might still survive up to one to two days.

Non-core vaccines are those recommended for animals whose geographical location and/or lifestyle places them at genuine risk of exposure to particular infections.

In the UK, this includes the following2-4.

● Feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) – in countries where FeLV is considered endemic (including the UK), this is considered a core vaccine for all kittens less than one year of age (whose final home environment might not be known), as well as older cats at risk of exposure (for example, with outdoor access). Only FeLV-negative cats (established via testing) should be vaccinated.

● Rabies – a legally required vaccine for travel to and from the UK.

● Bordetella bronchiseptica – this vaccine is not routinely used in pet cats, but might be used in a multi-cat household where infection is confirmed.

● Chlamydia felis – see B bronchiseptica.

Discussion with an owner regarding whether their indoor-only cat should be vaccinated and how frequently, relies on an individual patient risk assessment, and should consider the following.

● The cat’s environment and lifestyle; for example, cattery visits, single or multi-cat household.

● Individual health factors, such as, pregnancy or immunosuppressive disease.

● The pathogen in question.

● Safety and possible adverse effects of the vaccine.

● Efficacy of the vaccine; for example, type (modified live/live attenuated or inactivated/killed) and minimum duration of immunity.

Clients should be informed of the level of protection given by vaccines. Vaccination against feline parvovirus, for example, confers a high level of protection against infection and subsequent disease. Conversely, vaccination against FCV and FHV-1, although having a major role in protecting cats from disease and reducing the severity of disease in infected animals, does not necessarily prevent infection with these viruses.

The presence of antibodies against FHV-1 and FCV are also not considered to be a reliable predictor of immune protection against these viruses2, which is important to note if considering serological testing (for more information, see the 2024 WSAVA Vaccination Guidelines).

All kittens should receive vaccinations for FPV, FHV-1 and FCV at 6 to 8 weeks of age, then every 2 to 4 weeks until 16 weeks of age, with a subsequent dose at 26 weeks of age or older according to the WSAVA guidelines2, keeping in mind that frequency and minimum age of administration will vary depending on manufacturer label instructions.

The necessity for annual booster vaccinations has been questioned, and suggestions made that the frequency of core vaccination for FPV, FCV and FHV-1 should be reduced to every three years, which is the recommendation according to the WSAVA guidelines for low-risk adult cats (indoor-only, single cat household with no cattery visits; Figure 2). However, as previously stated, individual product data sheet recommendations vary within the UK, and any decision regarding reducing booster frequencies should be made only after discussion and with informed consent of the owner4.

Figure 2. An indoor-only cat is still at risk of pathogens (such as feline parvovirus) being brought into the home on the owner’s clothing and footwear. Image © Nichizhenova Elena / Adobe Stock

Vaccination of adult cats should, nonetheless, be assessed at least once yearly as part of a health assessment and, if necessary, modified on the basis of the individual cat’s risk assessment; for example, if an indoor cat is visiting a boarding cattery, a core vaccination booster is recommended a few weeks before possible exposure2. Although the benefits of vaccination by far outweigh the risks, adverse reactions to vaccines do occur. Most are mild, but severe adverse reactions, such as injection site sarcomas, are possible, though the incidence is believed to be low in the UK (1 per 5,000 to 12,500 vaccination visits)5.

Choosing injection sites where surgery would likely lead to a complete cure, such as the tail and distal limbs (due to the potential for amputation), is recommended, as well as recording of sites at each vaccination appointment5.

Parasiticides not only play an important role in the prevention and treatment of various parasites in cats (for example, fleas, ticks and worms), but also in protecting humans from associated zoonotic diseases.

In more recent times, concerns about environmental contamination and the possible effects of parasiticides on wildlife and ecosystems have led to the BVA and other key veterinary organisations recommending that veterinary professionals shift to a risk-based approach based on the pet’s individual health and lifestyle factors, as well as the potential risk to human health (zoonotic disease is more likely in very young, elderly or immunocompromised individuals)6.

It is also important to consider the detrimental effect a parasite burden can have on the human-cat bond, as this can be very unpleasant for owners and caregivers to manage.

The most common intestinal worms affecting cats in the UK are roundworms and tapeworms. Most infected cats do not show clinical signs; however, kittens are vulnerable to disease, and heavy burdens of worms in adult cats might cause weight loss, vomiting and diarrhoea, irritation around the anus and failure to thrive.

Importantly, while worms can sometimes cause problems for the cat itself, some worms can also be passed on to humans and, on rare occasions, can be a cause of serious human disease. For these reasons, regular treatment of cats and kittens to prevent or eliminate endoparasites is very important.

The two common roundworms of cats are Toxocara cati and Toxascaris leonina. Eggs from these worms are passed in faeces and can remain viable in the environment for several years. Cats might ingest eggs directly from a contaminated environment or by eating infected prey.

T cati is also passed from a queen to kittens through the milk she produces. Whenever a cat is infected with roundworms, some larvae remain dormant in tissues in the body. This usually causes no harm, but when a female cat becomes pregnant, these larvae migrate to the mammary glands and are excreted in the milk she produces for the kittens. This is a very common route of infection, and we should assume that every kitten will be infected with T cati as a result.

Tapeworms are generally long flat worms composed of many segments. Mature segments containing eggs are released from the end of the tapeworm and are passed in faeces. These segments often resemble grains of rice and can sometimes be seen on the hair around the anus of the cat, in the faeces and on the cat’s bed.

To complete their life cycle, all tapeworms require an intermediate host to first eat the eggs from the environment, and then the cat will become infected by eating the intermediate host. The most common tapeworms that infect cats worldwide are Dipylidium caninum and Taenia taeniaeformis.

D caninum is transmitted to cats by fleas. The immature flea larvae ingest the eggs of the worm, but infection is then passed on to a cat when it swallows an infected flea during grooming. It should be assumed that any cat infected with fleas also has D caninum (and vice versa). It is also a potential zoonosis if infected fleas or lice are ingested (although this is rare).

T taeniaeformis is contracted when cats eat infected prey (commonly rodents such as rats and mice), and so, infection occurs most commonly in cats that hunt and is, therefore, a reduced risk in indoor-only cats.

In addition to intestinal worms, cats can be infected with a variety of other endoparasites in other sites of the body. In the UK, these most commonly include the following.

● Aelurostrongylus abstrusus – lungworm.

● Protozoa – for example, Toxoplasma species, Giardia species.

● Dirofilaria immitis – heartworm (endemic in some European countries, important for cats with relevant travel history).

To assist veterinary professionals in suggesting rational control measures, the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites, an independent advisory board comprised of parasitology experts, identifies risk factors that impact the likelihood of infection with internal and external parasites (Panel 1).

● Age: kittens assume roundworm infection from the queen and increased susceptibility to clinical disease from parasitic infection (also a consideration for senior and super-senior cats with concurrent chronicdisease)

● Health status: immunocompromised, chronically ill or stressed cats are also at increased risk of clinical signs from endoparasite infection

● Pregnant or lactating queens: consider treatment of roundworms to prevent transmission to kittens (with an effective product that is labelled as safe to use)

● Environment: cattery visits, multi-cat households, some outdoor access (confined yard or catio), recently adopted as a stray or from a high-volume rehoming centre, risk of flea infestation – such as living with dogs)

● Nutrition: feeding of raw meat or offal and the possibility of hunting/access to prey (for example, access to confined garden area or catio)

● Travel history: Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm) endemic in certain countries in Europe

● Owner health status: cats sharing a home with children less than five years of age or immunocompromised individuals are considered at increased risk of zoonotic disease6

Kittens should be frequently treated against roundworms from three weeks of age to every two weeks until weaning and then monthly until six months old, when their risk of infection and other lifestyle factors should be re-assessed by a veterinary professional. For adult cats that live exclusively indoors, do not hunt and are otherwise free of the risk factors outlined, treatment for roundworm and tapeworm might be considered at a reduced frequency, or faecal examination performed at the clinician’s professional discretion6.

As discussed, the shift should be made to offering individualised care based on regular assessment of the cat’s health, lifestyle and environmental factors, and a tailored treatment plan created with mutual consent and understanding. If any risk factors are identified, the frequency of endoparasite treatment should be tailored to best prevent and treat disease for both cats and humans alike.

Recommendations suggest effective treatment at a minimum of four times a year or faecal analysis performed (depending on the active ingredient of the product used and the prepatent period of the parasite in question)7.

Advising cat owners of indoor-only cats on effective ectoparasite control will have a positive impact on the health and well-being of their pets because cats are still at risk of humans and other animals bringing them into the home environment.

The most common flea found on cats and dogs is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), and the most commonly encountered ticks in the UK are Ixodes species. Occasionally, rabbit and hedgehog fleas might be found on cats. While many cats live with fleas and show minimal signs of infestation, control of fleas and ticks is advisable because of the following points:

● The cat flea carries the larval stage of the tapeworm D caninum.

● Fleas and ticks can transmit other infectious agents; for example, vector-borne diseases such as bartonellosis (cat scratch disease).

● High flea and tick burdens can cause weakness, anaemia and death – particularly in young kittens.

● The development of flea allergy dermatitis or hypersensitivity severely affects the well-being of affected cats.

● The presence of fleas and ticks can impact the cat-human bond.

Risk factors for indoor cats include the number of pets in the house – particularly other cats and dogs with outdoor access, or any access to other cats through a catio or a garden space, as well as a warm environment.

Unfortunately, our centrally heated homes with fitted carpets provide ideal conditions for the year-round development of fleas, and regular prophylaxis should be recommended alongside frequent vacuuming (bags should be immediately and carefully disposed of) and regular coat checks (keeping in mind cats are highly effective at grooming and removing ectoparasites).

Treatment recommendations for ectoparasites will depend on the cat’s individual risk factors and might be influenced by the owner’s preferences and lifestyle. However, year-round protection is recommended for cats affected by flea allergy dermatitis/hypersensitivity.

Use of effective products at the correct dose (including application technique of a spot-on product), avoidance of hand contamination, and careful disposal of cat litter and product packaging are not only important for cat and human health, but also recommended to help reduce environmental contamination (for more information, see the BVA, BSAVA and British Veterinary Zoological Society policy position on the responsible use of parasiticides for cats and dogs)6.

“Optimal health care for cats requires regular veterinary examinations and preventive health care advice”

When considering a parasite treatment to recommend, alongside the effectiveness of the active ingredients against the target parasites and safety for use on the individual cat (in particular young kittens, pregnant or lactating queens), the easiness of applying/administering the product is critical for improving owner compliance and cat well-being. An online survey by Taylor et al, “Online survey of owners’ experiences of medicating their cats at home”, revealed the following information8:

● Around half (50.7%) of cat owners were “sometimes” or “never” provided with information or advice on how to administer medication, but 91.8% of those given information found it “somewhat” or “very” useful.

● More than half (53.6%) of owners sought information from the internet about how to administer medication.

● Cat owners rated tablets as significantly harder to administer than liquids; 53% chose liquids as their first-choice formulation while 29.3% chose tablets.

● Just more than half (51.6%) of owners reported that medicating their cat(s) had changed their relationship with them; 77% reported that their cat(s) had tried to bite or scratch them when medicating.

These results highlight the need to avoid having set parasite treatment protocols in clinic, as every cat is an individual, and where one cat will happily accept a spot-on formulation, another might prefer a tablet, and it should not be assumed all cats and owners will be happy with the same formulation. Involving the owner in the decision-making process is essential to aid compliance.

Figure 3. A cat wearing a quick-release collar. Image © sheilaf2002 / Adobe Stock

Safety concerns to consider when using ectoparasite treatments in cats are to avoid those formulated for use in dogs, as these might contain permethrin, which is highly toxic (and can be fatal) to cats. Owners with both dogs and cats at home might be inclined to use the same product on both species. Close contact with recently treated dogs might also induce toxicity in cats, including sitting on the same furniture. If recommending a flea collar, it is important to ensure it has a safety snap-open/quick-release buckle (Figure 3) to avoid injury, should the collar be caught on furniture, or the cat accidentally escapes the home.

Optimal health care for cats requires regular veterinary examinations and preventive health care advice. Consistent messaging from the entire team is crucial in ensuring owners are aware of why and when they should be bringing their cat(s) in for a health check.

Alongside vaccination and parasite treatment advice, a wellness programme should lay down a foundation for routine monitoring tests (for example, blood pressure, routine blood and urine tests) and examinations, as well as reinforce why they are beneficial for a cat’s health and well-being. Long-term compliance with a wellness plan is far more likely to be achieved if mutual agreement on the plan and course of action is reached at the outset between the client and the veterinary team.

To learn more about the recommended examinations and tests recommended for cats at different life stages, visit www.catfriendlyclinic.org9

It is the professional responsibility of veterinary professionals to ensure that not only is the cat’s physical preventive health care considered, but also to provide advice on its emotional and cognitive needs, to ensure all three components of the health triad are met, as they are inextricably linked and equally important10.

An indoor-only cat’s well-being might be compromised by their lifestyle, as they have reduced opportunities in an indoor environment for many natural behaviours, such as hunting and exploring. This might increase the risk of boredom and frustration, as the home environment is generally designed to meet the owner’s needs, but not always the cat’s environmental needs.

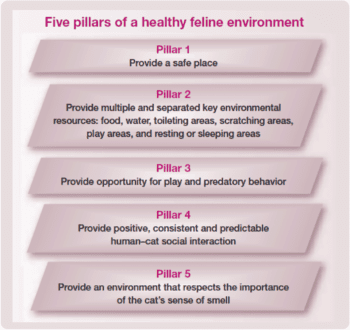

The risks to indoor-only cats, such as sharing space with incompatible cats in multi-cat households and boredom or frustration, might not be easily recognised by owners. However, some cats experiencing these negative emotions begin to display behaviours that owners might find difficult to cope with, such as scratching furniture, spraying, increased vocalisations or inter-cat aggression. Therefore, it is important to educate all cat owners on how they can meet their cat’s physical, emotional and cognitive needs by providing education on the “five pillars” of a healthy feline environment (Figure 4)11.

Veterinary professionals have an important role to play in educating cat owners and caregivers that preventive health care for their indoor-only cat is just as important as for a cat with outdoor access.

By performing individual risk assessments for each patient, wellness plans can be tailored to provide

an appropriate level of protection while establishing trust, improving compliance and working together to ensure cats receive a high standard of veterinary care – where equal consideration is given to both their physical and emotional health, to optimise their well-being.

References

1. Cats Protection (2023). Cats Report: Cats and Their Stats UK 2023, tinyurl.com/25fjjmrh

2. Squires RA et al (2024). 2024 guidelines for the vaccination of dogs and cats – compiled by the Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA), J Small Anim Pract 65(5): 277-316.

3. Stone AES et al (2020). 2020 AAHA/AAFP feline vaccination guidelines, J Feline Med Surg 22(9): 813-830.

4. BSAVA (2021). Position statements: vaccination, tinyurl.com/yucw3d3h

5. Hartman K et al (2015). Feline injection-site sarcoma: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management, J Feline Med Surg 17(7): 606-613.

6. BVA, BSAVA and British Veterinary Zoological Society (BVZS; 2021). BVA, BSAVA and BVZS policy position on responsible use of parasiticides for cats and dogs, tinyurl.com/msc353mn

7. European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP). ESCCAP UK and Ireland guidelines GLs 1, 3 and 6, 2012-2021, www.esccapuk.org.uk

8. Taylor S et al (2022). Online survey of owners’ experiences of medicating their cats at home, J Feline Med Surg 24(12): 1,283-1,293.

9. International Cat Care (2022). Recommended examinations at different life stages, tinyurl.com/3p3xk9ty

10. International Society of Feline Medicine/American Association of Feline Practitioners (2021). General principles of feline well-being, J Feline Med Surg 23(11): 1,072-1,073.

11. Ellis SLH et al (2013). AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines, J Feline Med Surg 15(3): 219-230.