16 May 2016

Dan O'Neill analyses presentations that demonstrated how an RVC resource shares information to understand companion animal disorders and improve welfare.

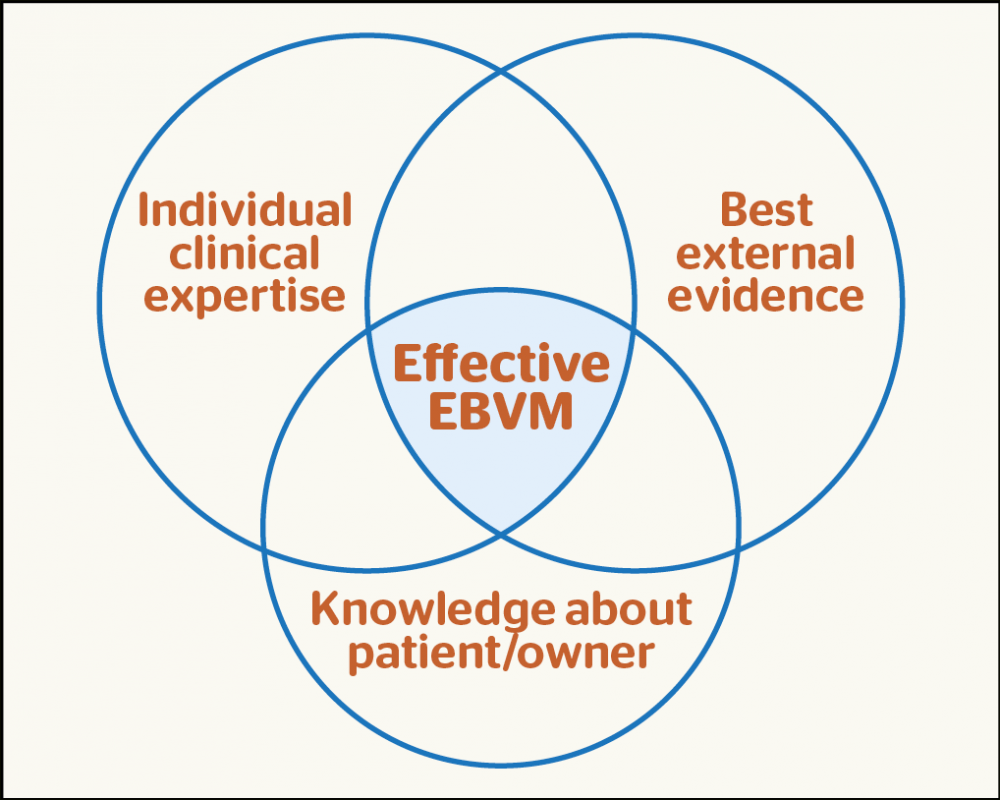

Figure 1. The three pillars of evidence-based veterinary medicine.

Evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM) is increasingly recognised as crucial to improving clinical outcomes and professional satisfaction in primary care veterinary practice.

However, to get the best out of EBVM in clinical practice, we need to understand what it is and how to identify the most useful EBVM for our needs.

Evidence-based medicine was reported as a new paradigm in human medicine in 1992 (Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, 1992) and extended to the veterinary sphere in 1996 (Bonnett and Reid-Smith, 1996). Defined in human medicine as the “conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient” (Doig, 2003), this definition applies just as well to veterinary care.

EBVM aims to optimise clinical effectiveness by building on the synergism between the three pillars of EBVM – good individual clinical judgement and expertise, combined with the practitioner’s knowledge of the patient/owner, supported by the best available scientific evidence (Figure 1; Sackett et al, 1996).

Good individual clinical judgement and expertise describes the high levels of clinical proficiency and judgement individuals can acquire through good-quality clinical experience and CPD. Although it can be difficult to measure, good clinical expertise can be reflected by increasingly accurate clinical diagnosis and improving clinical outcomes over time.

A clinical audit assesses, evaluates and improves measurable procedures for each stage of clinical care, diagnosis and intervention. RCVS Knowledge explains how to carry out a clinical audit, so practices and individuals can evaluate what they are doing well and where improvements can be made (RCVS Knowledge, 2016).

Application of knowledge about the patient and the owner may be reflected by more thoughtful and compassionate identification and incorporation of the patient’s welfare needs, as well as the motivations of the owner when making clinical decisions.

The best available scientific evidence refers to relevant research from patient-centred clinical research and informs on topics such as disorder prevalence and risk factors, accuracy of diagnostic tests and prognostic advice, and the efficacy and safety of therapeutic, surgical and preventive or intervention regimens.

Two of the three pillars of EBVM – individual clinical expertise and knowledge about patient/owner – are under the control of clinicians and should, naturally, increase and improve with time. However, the final pillar – best external evidence, relating to the availability of reliable and relevant scientific evidence – presents a major problem to EBVM.

Many published veterinary clinical papers are based on referral caseloads heavily filtered by factors such as disorder types and severity, the financial freedoms given by owners and by insurance status, geographic location and the additional facilities and expertise at referral centres (O’Neill et al, 2014). For these reasons, although relevant for academics working in referral environments, clinical evidence from referral populations often applies poorly to primary care caseloads.

Reliable evidence for primary care practitioners must relate to the typical caseloads and clinical management employed in the primary care world and, ideally, should be derived from large-scale primary care studies set in the same country where the evidence will be used. Sadly, until recently, few publications have met these criteria to be classified as relevant primary care EBVM.

Faced with a lack of relevant evidence, vets often make clinical decisions based on poor, or even non-existent, evidence and fall back on opinion-based or best-guess judgement. It is little wonder clinical medicine has been described as “the art of making decisions without adequate information” (Sox, 1996).

This deficiency of evidence on basic veterinary questions, such as “what are the most common disorders recorded in dogs and cats in the UK?” and “how long do UK dogs and cats live?” led the RVC to develop the VetCompass programme as a primary care veterinary data resource now revolutionising EBVM in the UK and several other countries.

VetCompass describes a philosophy where our cumulative veterinary clinical experience is harnessed to improve companion animal welfare. Supporters include the BSAVA, the BVA, the RCVS, the SPVS, The Kennel Club, International Cat Care, the RSPCA and Dogs Trust.

Designed by primary care practitioners, epidemiologists and clinical specialists, a key feature is operational invisibility in the consulting room; veterinary practitioners record their clinical data as normal, with no requirement for even a single extra mouse click.

VetCompass has developed research methods that use the enormous amount of clinical information practices already record. Elimination of “time-cost” barriers is critical to encouraging busy practitioners to participate in practice-based research.

Options to record standardised coding of the demography and disorders of patients are offered via the Veterinary Nomenclature Codes (www.venomcoding.org), but are not obligatory. To participate in VetCompass, practices agree to display posters and leaflets that promote their involvement in the project to clients.

Clinical data is shared from practice management systems to a secure database at the RVC. Participating practices have online access to their data, which has been cleaned and prepared for research, and which practices can use for their clinical audit or other practice-based research.

In EBVM style, this background seeks evidence VetCompass makes a meaningful contribution to EBVM. The evidence strongly supports a substantial EBVM impact from participating UK veterinary practitioners.

To date, VetCompass has generated 16 peer-reviewed publications, available at www.rvc.ac.uk/vetcompass/learn-zone

However, BSAVA Congress provided the most recent example of the real impact of this novel research resource. Eight oral clinical research abstracts and one poster were presented from the VetCompass stable (Figure 2).

This breadth of research and researchers is testament to the power of practice-derived clinical data to expand our understanding of the primary care world, with presentations covering multiple species (cats, dogs and rabbits), disorders and species/breed-based studies (Table 1).

Delving into the clinical course of individual disorders in primary care practice provides useful clinical and benchmarking evidence for practitioners.

Disorder-specific studies can highlight the frequency and risk factors for disorder occurrence and answer relevant clinical questions on diagnostic, therapeutic, surgical and referral outcomes. Such knowledge helps practitioners improve their diagnostic skills and provide evidence-based recommendations to clients with respect to disease prevention, management and prognosis.

Alex Riddell, during her final year VetMB elective project at the University of Cambridge, explored the prevalence and risk factors for urinary incontinence in dogs. Her study of 210,824 dogs identified a prevalence of 2% (3.1% in females and 0.9% in males).

Breeds with the highest odds of disease included the boxer, border collie, West Highland white terrier and German shepherd dog.

Overall, 36.8% of affected animals received medical treatment.

Caitlin Boyd, for her Applied Animal Behaviour and Animal Welfare thesis at the University of Edinburgh, examined mortality and relinquishment ascribed to undesirable behaviours in dogs younger than three years.

She reported 24.8% of 307 relinquishments were ascribed to undesirable behaviours, with aggression the most common cause.

Of 1,421 dogs younger than three years that died, 36.2% were attributed to undesirable behaviours, with aggression also the most common cause. The Staffordshire bull terrier was the breed with the highest odds of death from an undesirable behaviour (2.1 times the odds of cross-breed dogs) and males had 1.5 times the odds of death from an undesirable behaviour compared with females.

Georgina Harris, during her intern year at the RVC, examined the epidemiology, clinical management and outcomes from road traffic collisions (RTCs) involving dogs.

Her study of 199,464 dogs identified 822 RTC cases, a prevalence of 0.4%. Younger dogs were at greater risk of RTC and males were 1.4 times at greater risk compared with females.

Diagnostic imaging was performed on 39% of cases, 33.7% received IV fluid therapy, 52.9% were hospitalised and 81.7% received pain relief. Overall, 22.9% of cases died from a related cause.

Megan Conroy, for her MSc in Veterinary Epidemiology at the RVC, looked at the number of cats attending emergency care practices after an RTC.

Using data from 33,053 cats, attending 50 Vets Now emergency clinics, She identified 1,407 RTC cases and reported a prevalence of 4.3%.

Cats aged 6 months to 12 months were at highest risk of being in an RTC and male cats were 1.3 times at greater risk compared with females. The head (32%), skin (27.5%) and pelvis (22.7%) were the most common body areas injured. Half of RTC cases were recorded with two or more injuries.

Fewer than 7% of cats died on arrival and a further 33% died or were euthanised during the emergency care period.

Analgesia (83.5%), IV fluid therapy (45.6%) and oxygen therapy (17.1%) were the most common treatments. Blood tests (36.5%) and radiographs (29.9%) were the most common investigations, with 62.1% of cats hospitalised.

The partial postcode data stored in VetCompass was used to compare geographic locations between neoplasia cases and controls.

The results showed evidence of statistically significant clustering overall, with increased relative risk around the London area and reduced risk in Cambridgeshire and Oxfordshire.

The author, supported at the RVC by The Kennel Club Charitable Trust, presented a poster examining patellar luxation in dogs. The study included 210,824 dogs, attending 119 primary care clinics in England, and identified an overall prevalence of 1.3%. The Pomeranian (6.5%), Yorkshire terrier (5.4%) and Chihuahua (4.9%) had the highest prevalence.

Medical management (analgesic, anti-inflammatory, chondroprotective agents) was used in 39% of cases and 13.2% of cases received surgical intervention. The median age at the first surgery was 2.9 years and 3.7% of cases were referred for further case management.

Many health issues are species or breed-associated. Studies restricted to specific species or breeds can help identify major health concerns in these groups and help prioritise health problems to improve animal welfare.

Hermien Craven, for her BVetMed final year research project at the RVC, explored the demography and health of rabbits attending primary care practices in England (Figure 2). Her study population included 6,357 rabbits, attending 107 veterinary practices in 2013.

The median age of rabbits was 3.1 years and the median bodyweight was 2.3kg. The population was 54.1% male, of which 76.3% were neutered, and 45.9% female, of which 72.7% were neutered. Insurance covered 11.5% of rabbits, 24.6% were microchipped and 38.3% were vaccinated.

Molar dental disease (8.6%), perineal soiling (5.1%) and overgrown incisors (4.8%) were the most common disorders recorded. The median age at death was four years, and 51.7% of deaths involved euthanasia. The most common cause of death among euthanised rabbits was myiasis (11.7%).

Elisabeth Darwent, during her final year BVetMed project at the RVC, compared the health of pugs and border terriers.

Based on clinical records from 1,015 pugs, obesity (13.1%) and corneal disease (8.7%) were the most common disorders, while data from 1,327 border terriers revealed dental disease (17.6%) and obesity (6.9%) as their most common disorders.

Pugs had a significantly higher prevalence for 9 of the top 24 disorders compared with border terriers, which had a higher prevalence for 4 of the top 24 disorders. This data highlights some health concerns for pugs and suggests priority could be considered for corneal and obesity issues.

Stephanie Phillipps, during her BVetMed final year project at the RVC, examined thoracolumbar spinal disorders in dogs attending primary care veterinary practices in England.

Based on a denominator population of 104,233 dogs, Stephanie identified a prevalence of 1%. On presentation, 84.8% of cases were ambulatory and 69.6% showed spinal pain. Intervertebral disc disease (35.5%) and spondylosis (22.1%) were the most commonly reported specific disorders.

Surgery was undertaken in 8.8% of cases and medical treatment was used in 88.7% of cases. Overall, 10.7% of cases were euthanised because of the disorder. The breeds with the highest odds ratio (OR) include the dachshund (OR 7.1), cavalier King Charles spaniel (OR 2.3), cocker spaniel (OR 1.8) and German shepherd dog (OR 1.7).

The breadth of research and the diversity of researchers presenting at BSAVA Congress cemented VetCompass as a premier resource for primary care EBVM worldwide and provides strong evidence UK practitioners can play an active role in the generation of clinical evidence relating to primary care caseloads and management.

VetCompass evidence will challenge many daily routine decisions in veterinary clinics and promises to dramatically increase our clinical effectiveness and improve animal welfare. The BSAVA Congress proceedings give further information on these abstracts.