3 Nov 2021

Matthew Best MA, VetMB, FANZCVS, MRCVS shares a case study in a young dog, and details examination through to diagnosis, treatment and prognosis.

Figure 1. A right lateral thoracic radiograph taken at presentation showing a mixed lung pattern, with some impression of nodular change.

A 12-month-old male neutered cavalier King Charles spaniel was presented to his primary care vet with a six-day history of lethargy, reduced appetite, and increased respiratory rate and effort without coughing. He had no significant medical history.

Examination revealed increased respiratory effort, with pink mucous membranes and bilateral pulmonary crackles on auscultation. Some resentment existed to abdominal palpation. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

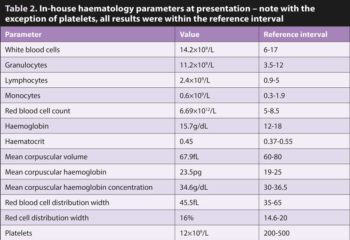

Biochemistry and haematology panels were run (Tables 1 and 2).

Thoracic radiographs showed a patchy bronchoalveolar lung pattern – a lateral radiograph is shown in Figure 1.

Furosemide, buprenorphine and cefuroxime were administered IV. An emergency referral was arranged and the patient was seen immediately.

Clinical examination was as described previously, with marked dyspnoea and no tracheal sensitivity.

The resentment to abdominal palpation was also appreciated on examination. Oxygen saturation was markedly reduced at 80% and this was confirmed with arterial blood gases which demonstrated partial pressure of oxygen was 42mmHg.

A blood sample was collected to assess platelets and coagulation parameters, and for a peripheral eosinophilia. The platelets were clumped and adequate, while prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times were within the reference intervals.

A manual estimate of the granulocyte differential was performed with an estimate of 70% neutrophils and 30% eosinophils; this is consistent with an eosinophil count of 3.7×109/L, which represents a significant peripheral eosinophilia.

The patient was pretreated with oxygen, then anaesthetised. A CT scan was undertaken of the chest and abdomen. This showed a patchy, generalised alveolar pattern with bronchial thickening, mild bronchiectasis and mild pulmonary lymphadenopathy (Figure 2).

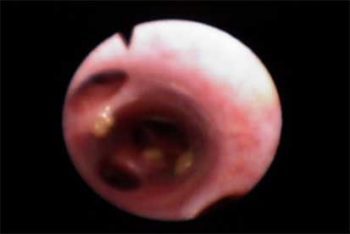

Bronchoscopy was performed that showed generalised mild hyperaemia of the mucosa with widespread mucopurulent exudate (Figure 3).

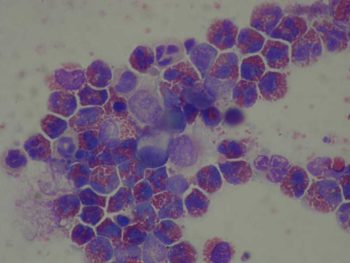

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was submitted for external cytology and analysis. In-house assessment of airway secretions showed an eosinophil-dominated inflammatory exudate with no infectious or neoplastic organisms identified.

Dexamethasone was administered

(0.4mg/kg IV) while still under anaesthesia and the patient was recovered with nasal oxygen therapy provided.

External cytology of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid confirmed eosinophilic inflammation without detection of any infectious agents or neoplastic cells (Figure 4).

Adequate oxygenation was achieved using nasal oxygen, but the patient remained oxygen dependent for 72 hours.

Within 24 hours of the dexamethasone injection his appetite had returned and the pulmonary crackles had resolved. At this stage the patient was transitioned to oral prednisolone, 2mg/kg every 24 hours.

The diagnosis in this case was eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (also described as eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia/eosinophils, eosinophilic granulomatous pneumonia and hypereosinophilic syndrome).

This is a hypersensitivity/immune‑mediated disease of unknown aetiology. It is most common in young dogs and while it can affect any breed, a predisposition for larger breeds – especially Arctic breeds – has been recognised. A reported increased incidence exists in female dogs.

Diagnosis hinges on the demonstration of an eosinophilic exudate without another underlying cause. Other possible causes include:

The signalment and presentation is characteristic and should raise suspicion for this disease, and thus direct the therapeutic investigations. This suspicion is further heightened in the presence of a peripheral eosinophilia, which is present in 50% to 60% of cases, including this one.

An interesting differential in this case was Pneumocystis, a fungal obligate parasite that has been recorded to cause respiratory disease with a particular predisposition in young cavalier King Charles spaniels.

Typically, weight loss occurs in this condition without necessarily a loss of appetite, and most commonly the inflammation is neutrophilic or mixed in nature.

Treatment for eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy is immunosuppressive corticosteroids that should be weaned over four to six months, in a similar fashion to other immune-mediated diseases.

The prognosis is variable, with the most significant factor being the involvement of other organ systems in the eosinophilic reaction.

While the abdominal discomfort raised the concern of visceral involvement, in this case the normal blood work and abdominal imaging make this unlikely.

Most cases restricted to the lungs have a good long‑term prognosis, making this a rewarding disease to treat.

Of course, not every case resolves as planned, and owners should always be warned of the risk of relapse and the possible need for long-term immunosuppression, potentially including steroid-sparing agents.

This patient showed a strong initial response to therapy. This is encouraging, and it is hoped he will follow a typical path and make a complete recovery as the prednisolone is gradually withdrawn over the coming months.