7 Nov 2016

James Guillem discusses the case of eight-year-old Zac, and asks: what do the radiographs show, and how would you confirm diagnosis?

Figure 1. Left lateral projection of the thorax.

Halfway through an out-of-hours shift, Zac, an eight-year-old, male neutered, domestic shorthair cat, is presented with signs of respiratory distress.

On examination, Zac had marked abdominal breathing, was bradycardic (heart rate of 130 beats per minute) and the location of his apex beat was displaced to the right. No adventitious lung sounds were heard during thoracic auscultation and the remainder of his physical examination was unremarkable.

Oxygen therapy was administered to Zac by free flow and a good response was noted after 10 minutes. His respiratory rate decreased from 68 to 32 respirations per minute and his abdominal breathing ceased. Haematology and biochemistry were performed and were both unremarkable. To further investigate the cause of Zac’s respiratory distress, thoracic radiographs were acquired under butorphanol sedation (Figures 1 and 2).

What do these radiographs show and how would you confirm the diagnosis?

The cardiac silhouette is globoid in shape, markedly enlarged both in width and height, and occupies around four intercostal spaces in width. The caudal border of the heart is in contact with the ventral aspect of the diaphragm, which is not clearly seen on the lateral view.

On the dorsoventral view, the central portion of the diaphragm is also not seen clearly. A mild generalised interstitial pattern is visible throughout the lungs. Mediastinal and pleural structures are within normal limits. Subjectively, falciform fat in cranial abdomen is reduced. The liver and stomach appear to be located in a normal position inside the abdomen. A small amount of new bone formation can be seen ventral to the intervertebral space between T11 and T12, consistent with spondylosis.

In summary, the main radiographic findings include marked cardiomegaly, loss of a clear diaphragmatic outline ventrally on the lateral view and centrally on the dorsoventral projection, and a mild bronchial lung pattern.

The mild bronchial lung pattern was most likely related to feline lower airway disease. The primary differential diagnosis for the appearance of the heart is a pericardial peritoneal diaphragmatic hernia (PPDH); however, further differentials include cardiomyopathy, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and pericardial effusion.

Echocardiography as a complementary technique to radiography was considered. It is a non-invasive procedure that provides more detailed information on the structure and function of the heart and peripheral structures, such as the aorta, vena cava and the pericardium.

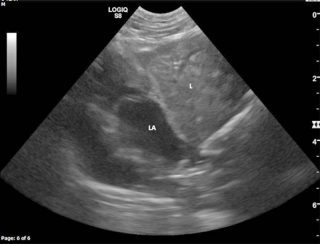

Zac’s echocardiography (Figure 3) revealed a solid and homogeneous soft tissue organ adjacent to the heart. The origin of this tissue could be traced back into the abdominal cavity and was continuous with the rest of the liver, confirming it was a herniated liver lobe.

The vascularity was not compromised, with colour Doppler ruling out liver lobe strangulation. The diaphragm could not be seen between these two structures, confirming suspicion of a PPDH; one of the most common congenital pericardial diseases in cats. Clinical signs include tachypnoea, dyspnoea and, in some cases, mild gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort with vomiting. However, cats with this condition are often asymptomatic and, therefore, this can be an incidental finding. In patients presenting with clinical signs, surgery should be considered, especially in those where hepatic or GI strangulation is suspected. In asymptomatic patients surgery is not mandatory, but close monitoring is advised, as they may show signs at a later time.

In Zac’s case, due to his age, the PPDH was considered likely to be an incidental finding and his clinical signs were more likely to be related to lower airway disease. He was stabilised overnight with oxygen therapy. Options for further investigation were discussed, such as bronchoscopy with a bronchoalveolar lavage or a CT scan. Zac was discharged following recovery, but was lost prior to follow up.