12 Nov 2024

Georgie Hollis discusses vacuum-assisted closure and its use, current and potential, in veterinary settings.

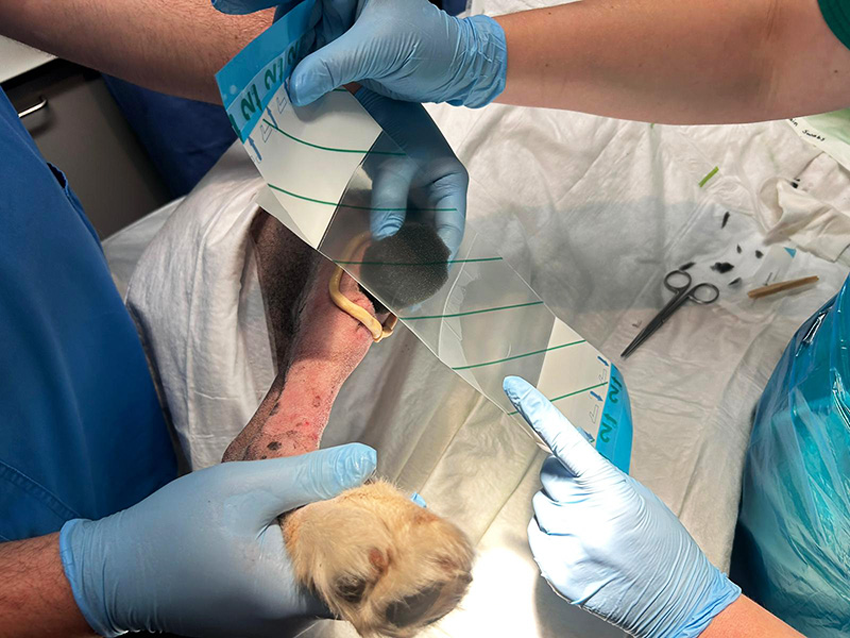

Figure 2. Application of a ring of ostomy paste around the wound provides a secondary seal to reinforce the drape.

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) or vacuum-assisted closure is a wound management method that allows a dressing to remain in place while exudate is actively sucked away from the wound bed. It also physically “pulls” the wound bed into the dead space, and so effectively reduces wound size. Therefore, it stabilises local tissues and encourages rapid revascularisation.

Early powered versions of NPWT systems showed their worth in military use, where the most complex of traumatic wounds inevitably pose significant clinical challenges. Lately, NPWT has become established across emergency, trauma, orthopaedic and community wound care settings, both pre-surgery and postsurgery, and importantly as an aid to management of chronic wounds.

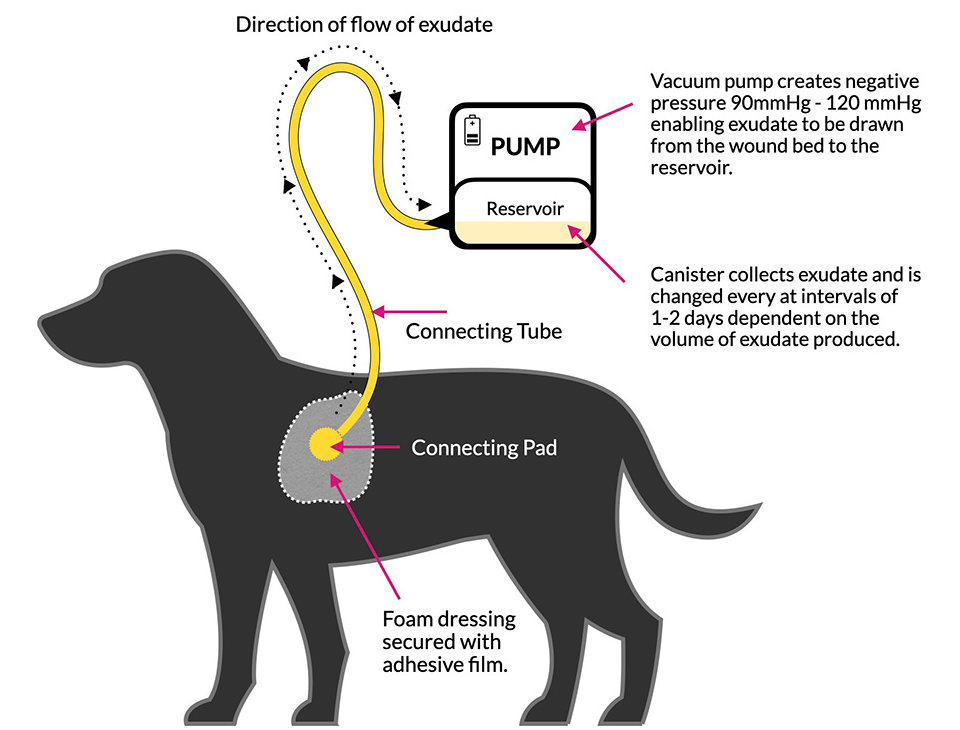

A typical NPWT device works by having a powered vacuum pump that effectively sucks the exudate from the wound to a remote reservoir. The reservoir, or canister, remains closed and retains the wound exudate safely and effectively; it is usually removable and disposable (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Illustration of a typical veterinary NPWT “set-up”.

The pump can be purchased or leased and the dressings that connect to it are single use and disposable. The “dressing end” of the NPWT system is made up of a foam pad, an adhesive drape and a connecting tube sealed in place with the layers of the drape. The other end of the tube is attached to the pump, so that exudate is drawn through the foam into the reservoir.

When the system is activated, a vacuum between 90mmHg to 120mmHg draws exudate through the dressing to the reservoir.

This exudate can be monitored remotely in the canister and assessed for volume and colour; these features may indicate deterioration or positive wound progression.

The volume of exudate produced will largely depend on the stage of healing, the extent and type of the wound site, and the size of the patient. Exudate levels, colour and viscosity in the canister can be visually assessed. Careful and regular assessment of the exudate harvested from the wound should be recorded.

A reduction in volume may indicate a positive progressive wound site status. The exudate is, of course, protein rich and this can, where the volume is high, represent a significant loss to smaller or malnourished patients; these may then need supplementary nutrition.

As the wound heals, the exudate volume will normally reduce and should also become clear. As an approximate guide, a standard 300ml canister will usually last one to two days in the early phases of healing and may last up to three days once the wound is in a proliferating/healing stage.

In contrast to its use in human health care, fixing the dressing to the patient is by far the biggest challenge. The adhesive film dressings may not adhere properly to greasy, hairy skin. Therefore, great care must be given to skin preparation prior to applying NPWT. If the seal is broken at any point during two days of use, the device will fail and a totally new dressing needs to be applied.

Dressing adhesion can be optimised in three ways. Firstly, the hair around the wound should be clipped very short and wide to ensure a stable attachment can be achieved. The more area available for the dressing to stick to, the more likely it will seal fully. Secondly, the skin around the wound should be cleaned carefully with a solution that removes oils and sebum. This should be followed by an alcohol spray that must be allowed to dry fully.

Some clinicians report a layer of Opsite spray (Smith and Nephew) on the skin can improve adhesion, while others prefer to use ostomy strips or paste (Figure 2) to create a secondary seal around the wound itself in case the dressing loses its adhesion.

Figure 2. Application of a ring of ostomy paste around the wound provides a secondary seal to reinforce the drape.

The original objective of NPWT was to seal the wound and enable a healthy wound bed to be achieved simply by removing exudate and facilitating rapid formation of healthy granulation tissue.

Stanley et al1 investigated NPWT in companion animals and demonstrated tangible benefits that were cost neutral compared to conventional open wound management.

The traumatic and open wounds treated with NPWT in this study showed faster development of granulation tissue, with longer intervals between dressing changes. The NPWT cases were suitable for reconstruction within 7 days as opposed to 14 days in wounds managed with standard moist wound healing methods. As the interval of dressing changes were longer, the NPWT group also benefited from fewer interventions, and as such reduced anaesthesia events compared to the standard group1.

The second (and somewhat counterintuitive) role for NPWT is in supporting surgical and reconstructed wounds that are prone to complications from oedema, tension and local tissue mobility.

The benefits of NPWT compared with open wound management include:

The following wound cases are appropriate for use of NPWT:

The benefit of NPWT is documented and papers that support veterinary use are enthusiastic about its future potential in both referral and first opinion practice. It has a strong potential to improve healing rates, reduce complications and improve overall patient outcomes.

Unfortunately, the availability and range of devices available for veterinary use has reduced in the past few years, as manufacturers focus commercial decisions on the highly profitable human sector.

While it is not impossible to purchase devices via the human supply chain, it can be difficult to source consumables directly and getting units serviced or supported can be very problematic. This may leave those with a unit somewhat compromised with limited access to consumables that may not fit their specific device.

Those keen to try NPWT may find it difficult to source a supplier, and the aftercare you would naturally expect from reputable instrument makers.