9 Dec 2020

Mike Davies BVetMed, CertVR, CertSAO, FRCVS reviews evidence on the transmission of food-borne protozoa and viruses to and between animals and humans.

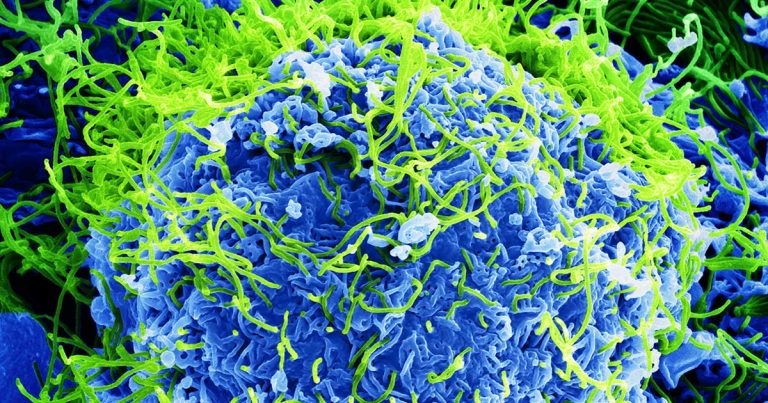

Colourised scanning electron micrograph of Ebola virus particles (green) found both as extracellular particles and budding particles from a chronically infected African green monkey kidney cell (blue); 20,000× magnification. Image: BernbaumJG / Wikimedia Commons

Pathogenic bacteria, protozoa, viruses and parasites are present in raw meats and fish, and can cause disease in humans, dogs and cats. But what is the risk from humans and pets sharing their environment?

In part one (VT48.47) I reviewed the risk associated with food-borne bacterial infections. In this article I shall review the scientific evidence regarding the transmission of food-borne protozoa and viruses to and between pets and people.

Toxoplasmosis is caused by intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, which can infect almost all warm-blooded animals, and about 350 human cases of toxoplasmosis are diagnosed in England and Wales each year (GOV.UK, 2016). Cats are the definitive host for this agent, whereas other species are intermediate hosts.

People are typically infected by three routes of transmission:

In a review (Said et al, 2017) the Government found a strong association between eating beef and Toxoplasma infection in the UK, although in the US infection is contracted especially from pork, lamb and venison. The authors concluded that these findings emphasise the need to ensure food is thoroughly cooked and handled hygienically – especially for those in vulnerable groups.

Dogs and cats fed raw food have a higher frequency of disease and exposure, as do captive exotic cats in zoological collections (Greene, 2006). Once shed, T gondii can survive in the environment for at least six months.

Serological evidence of widespread exposure to T gondii is well documented, and many infected individuals may be asymptomatic, but the clinical signs of toxoplasmosis are so variable and non-specific (Panel 1) that many cases undoubtedly go undiagnosed because of lack of diagnostic investigation.

Dog

Cat

Human

Signs may be seen at birth or develop several months or years later, such as brain damage, hearing loss and vision problems.

The risk to humans is highest from handling or ingesting raw meats or contact with oocysts shed by infected cats. Good hygiene after handling foods and cats/cat litter trays can minimise these risks, but oocysts can remain in the environment for many months. Freezing meat at -12°C for at least 24 hours can kill T gondii organisms.

Norovirus is one of the most common causes of acute gastroenteritis in humans in the UK, with an estimated 74,000 cases annually. Norovirus outbreaks have also been reported in dogs (Ntafis et al, 2010), and transmission can occur between pets and humans (Summa et al, 2012).

In this latter study, human strain of norovirus HuNoV was detected in four faecal samples from pet dogs that had been in direct contact with symptomatic persons. Three of the positive samples contained genotype GII.4 variant 2006b or 2008 and one GII.12. All NoV-positive dogs lived in households with small children and two dogs showed mild symptoms.

Norovirus is highly contagious, but can also be acquired from eating undercooked foods or handling raw meats.

Pseudorabies virus (Aujeszky’s disease) is caused by a type 1 porcine herpesvirus suid herpesvirus 1 (Swine Health Information Center, 2015). Infections with the highest mortality rate are those affecting suckling pigs born to a susceptible sow. Other mammals – such as humans, cattle, sheep, goats, cats, dogs and raccoons – are also susceptible. The disease is usually fatal in these animal species, except humans.

In dogs, infection is believed to be transmitted by eating infected pork or offal (Kotnik et al, 2006; Cay and Letellier, 2009; Zhang et al, 2015). Whether this virus can be transmitted from dogs or cats to humans is unknown, but the virus can spread by aerosol so minimising exposure risk is important.

In December 2016 a veterinarian working in a cat shelter in New York contracted bird flu (avian influenza A[H7N2] virus) from infected cats (with avian influenza A/feline/New York/16-040082-1/2016) in the shelter in which he worked. Some of the cats died (Marinova-Petkova et al, 2016). The source of infection to the cats was not documented.

In total, more than 100 cats tested positive for avian influenza H7N2 across all New York City shelters (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, 2016). In this outbreak the original source of the virus was not determined, but in previous feline cases infected meat was the source.

In 2003, two tigers and two leopards in a zoo in Thailand died from an H5N1 viral infection. In 2004, a number of domestic cats in Thailand, as well as another tiger, also died from infection with this avian influenza strain. Domestic cats in Germany also contracted the H5N1 virus.

Research showed that both the wild and domestic cats involved in the outbreaks had a history of eating raw meat from infected birds (either poultry or wild birds). Cats may also become infected through contact with other infected cats, through faeces, urine or nasal discharge.

In October 2004, captive tigers fed on fresh chicken carcases began dying in large numbers at a zoo in Thailand. Altogether, 147 tigers out of 441 died of infection or were euthanised (World Health Organization, 2006). So, feeding infected raw poultry meat to cats would present a potential risk to humans. Avian flu has also been found in the microbiome of dogs in the UK (Petbiome – unpublished data).

The covid-19 virus is believed to have originated in meat products in China. Cats and dogs have been infected, but so far these cases are thought to have been transmitted from people and no confirmed reports exist of transmission to humans from pets.

Nevertheless, feeding raw meat of unknown origin to pets carries with it the potential risk of transmitting covid-19 and other food-borne exotic zoonotic viruses.

Ebola virus is a highly contagious viral haemorrhagic disease that is often fatal in humans, and human outbreaks almost certainly originate from contact with bush meat that comes from a variety of wild animals, including bats, non-human primates (for example, monkeys), cane rats (grasscutters) and duiker (antelope).

In Africa, human infections have been associated with butchering and processing meat from infected animals. In the latest outbreak in 2013, the first case – an infant named Child Zero, who died on 6 December 2013 – lived in a family that hunted two species of bat that carry the Ebola virus.

It is estimated that every year, 7,500 tonnes of bush meat is imported into Britain, according to wildlife charity the Born Free Foundation (Goldhill, 2014).

Ebola is a zoonotic disease, but fortunately the current risk of transmission to pets, and between humans and pets, is thought to be extremely low, although German authorities did destroy a dog that was in contact with an infected human just in case.

The American Veterinary Medical Association has issued guidance on Ebola in dogs for public health officials at https://bit.ly/3pIBVi9

The UK Government recognises that “recorded human cases represent only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ as many patients do not seek medical attention or their doctor does not request laboratory investigation and a positive result is either not notified or the occurrence of the disease is not notifiable” (GOV.UK, 2019).

Similarly, in veterinary medicine animals carrying zoonotic organisms may be asymptomatic and so no diagnostic tests will be conducted, and if they are symptomatic the cause of disease in individual animals may not be fully investigated, and investigations and reports of food-borne infection are most likely if a group of animals is affected.

More cross-profession collaboration is needed to fully determine the prevalence of food-borne zoonoses and transmission between species, and to establish the associated risk from feeding raw meats to pets. Currently, a medical GP is unlikely to ask patients about pet ownership and concurrent disease, and veterinary clinicians are unlikely to ask owners if family members are unwell when an animal is affected.

It is an undeniable fact that raw meats carry potentially serious pathogenic organisms that can be transmitted to humans and pets. Some of these can then be transmitted between the species.

The true incidence of transmission of food-borne pathogenic organisms between pets and humans is unknown, as are the numbers of clinically affected individuals; however, transmission of infections and comorbidities have been documented. More collaboration is needed between the veterinary and medical communities to establish the true incidence and risks involved.

After reviewing the evidence, in the author’s opinion feeding raw meats to pets is reckless, irresponsible, and for the veterinary and allied professions ethically questionable. Endorsing the feeding of raw foods to pets can result in food‑borne infection and serious harm, which could result in legal liability.