6 May 2019

Jeanette Bannoehr summarises the factors that cause this common issue in dogs and describes the management options available.

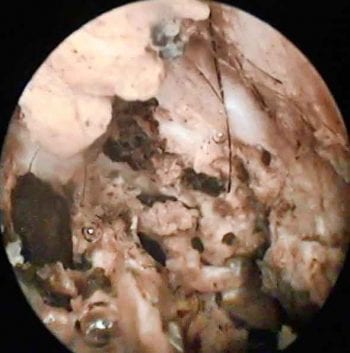

Figure 1. Video otoscopy image of the horizontal ear canal, showing an exophytic growth causing partial obstruction and allowing debris to get trapped behind (in front of the tympanic membrane). Histopathology confirmed an inflammatory polyp with bacterial infection.

Canine otitis externa (OE) is a daily presentation in general practice and frequently seen at referral level.

Although uncomplicated cases may resolve with a single course of symptomatic topical treatment, chronic recurrent otitis is common and can be challenging to manage.

This article summarises the aetiopathogenesis of canine OE and latest treatment approaches, with a focus on the management of multidrug-resistant and biofilm-forming bacteria.

OE is considered a multifactorial disease. The classic differentiation into primary, secondary, predisposing and perpetuating factors contributing to the disease is still valid, and awareness of these factors is helpful for a strategic work-up of OE patients.

Primary factors are the underlying or primary pathological processes, leading to aural inflammation and subsequent disturbance of the epithelial barrier protecting the external ear canal. Examples are:

Secondary factors can develop as a result of the abnormal micro-environment created by primary factors, and include bacterial and/or yeast overgrowth or infection.

Predisposing factors do not cause OE on their own, but make the ear more susceptible to the development of OE. These include:

Perpetuating factors can maintain ear inflammation, even if primary and secondary factors have been addressed. They create a favourable environment for debris accumulation and microorganisms in the ear canal. Examples are:

The following steps are helpful in any case of canine OE:

Dermatological examination: to assess for the presence of skin lesions suggestive of the driving primary factor (for example, allergy, hypothyroidism). However, unilateral or bilateral OE can be the only apparent sign of an underlying allergic or endocrine disorder.

Acute, uncomplicated “flares” of OE are usually treated with a combination of an ear cleanser and topical medication. A typical treatment period would be 14 days, followed by a check-up to assess whether treatment response has been satisfactory.

The frequency of ear cleaning is based on the amount of cerumen present in the ear canal, but varies between twice daily and twice weekly.

Licensed topical ear medication generally contains a combination of corticosteroid, antibiotic and antifungal. While the use of a topical anti-inflammatory corticosteroid is beneficial in most cases, the combination of an antibacterial and antifungal component is not always needed, and of concern in the age of antimicrobial resistance.

Performing in-house cytology gives the immediate answer as to whether bacterial, yeast or mixed overgrowth/infection is present.

Corticosteroids differ in their relative potency. For example, mometasone furoate has a substantially higher potency than prednisolone or hydrocortisone. The corticosteroid should, therefore, be chosen based on the degree of inflammation, but with awareness of potential systemic absorption – especially in longer treatment courses.

Antifungals used in commercial topical products are generally efficient against Malassezia yeasts found in OE, with resistance rarely reported.

The antibiotic needs to be chosen with care. In the author’s opinion, using a tier system for antibiotic treatment is helpful, not only for systemic, but also for topical treatment:

Newer topical treatment options for OE include:

Further work-up is mandatory in patients with recurring episodes of OE, including an elimination diet trial with or without allergen serology/intradermal testing, thyroid assessment and diagnostic imaging.

If the primary factor cannot be clearly identified or resolved, frequent topical treatment may be necessary to maintain long-term control of relapses and secondary factors. In these cases, the author aims to achieve a twice-weekly regime of ear cleaning with or without topical anti-inflammatories.

The use of less-than-daily antimicrobials should be avoided due to the risk of creating bacterial – or, less commonly, fungal – resistance.

Cases where multidrug-resistant bacteria have been identified are more challenging to treat – especially when Pseudomonas species are involved. These Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria are present ubiquitously in the environment, but not part of normal aural flora.

Pseudomonas species are well-known for their intrinsic resistance to various antimicrobials, and they can acquire further resistance if treatment is insufficient – for example, through low drug concentration, infrequency of application, or short course of treatment.

Treatment of Pseudomonas otitis needs to be closely monitored (check-ups every two weeks) and cytology performed every time. If no improvement occurs with an appropriate treatment plan, bacterial culture and sensitivity testing should be repeated.

Topical silver sulfadiazine has shown in vitro activity against Pseudomonas species and can be used if isolates are drug-resistant to all other readily available antimicrobials. In the author’s experience, once-daily application at home – combined with regular ear flushing at the clinic – results in a good success rate.

Additionally, Pseudomonas species can create biofilms. When the bacterial cells attach to surfaces, they start producing a protective matrix. The matrix increases the minimum inhibitory concentrations of antimicrobials needed and makes the bacteria more resilient to treatment. Different studies found between 40% to more than 90% of Pseudomonas isolates produce biofilm in vitro (Figure 4).

Biofilm formation has also been demonstrated in other bacterial species commonly isolated from OE, such as Staphylococcus pseudintermedius.

TrisEDTA damages the bacterial cell wall and, subsequently, facilitates antimicrobial penetration. In vitro studies have demonstrated it lowers antimicrobial minimal bactericidal and minimal inhibitory concentrations for Pseudomonas species.

N-acetylcysteine has mucolytic properties, and has been shown to reduce already produced biofilm and prevent new biofilm formation. Topical N-acetylcysteine products are available in combination with trisEDTA as an ear/skin solution, and with plant-extracted essential fatty acids and essential oils as an ear cleanser.

Mechanical destruction of biofilm by ear flushing/deep cleaning under general anaesthesia is also beneficial.

The author uses a combined approach of repeated ear flushing/deep cleaning at the clinic under general anaesthesia, and ear flushing plus antimicrobial/anti-inflammatory treatment at home.

If the tympanic membrane cannot be fully assessed on otoscopic examination – for example, due to overlying debris/discharge, severe inflammation/stenosis or lack of patient cooperation – an ear flush and deep clean under general anaesthesia should be performed.

However, if this is not possible, the following medications are considered “safer” for topical use with a potential ruptured tympanic membrane:

Systemic anti-inflammatory treatment can be useful – especially in patients with severe inflammation and stenosis of the ear canal, or frequent OE flares despite topical treatment and attempted correction of primary factors:

Systemic antimicrobials are controversial for treatment of OE, as they may not reach sufficient concentration in the ear canal; the author would not recommend their use. However, they may be of benefit if the ear canal is eroded/ulcerated, or in cases where topical treatment is impossible.

Successful long-term management of chronic OE requires a combination of identifying and controlling primary and secondary factors, ideally before perpetuating factors become irreversible.

Besides thorough history taking and clinical examination, cytology should be performed at initial presentation and check-up appointments to monitor disease progression and treatment response. Bacterial culture and sensitivity testing is warranted if rod-shaped bacteria are seen on cytology, or if bacteria persist despite appropriate treatment. Diagnostic imaging is also useful to assess the extent of ear disease and to detect occult OM.

In acute, uncomplicated OE, a combination of a commercial ear cleaner and licensed ear drop for 14 days, followed by re-assessment, may be sufficient. In chronic, recurrent OE, work-up for underlying conditions should be performed as disease control cannot be achieved without the correction of primary factors.

In cases of multidrug-resistant bacteria and biofilm production, a combination of ear flushing under general anaesthesia, ear flushing at home with anti-biofilm products, and directed topical antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended.