2 Oct 2017

Dikla Arad and Aurora Zoff on the case of a 13-year-old neutered female with a history of laboured breathing and wheezing, with signs progressively worse over the preceding months.

IMAGE: Pixabay/mburleson.

You are presented with a 13-year-old female, neutered Labrador retriever. The dog has a history of laboured breathing (worse after exercise) and wheezing. The signs were becoming progressively worse over the past few months.

The dog collapsed yesterday while regurgitating and was cyanotic. The owner brought her to a veterinary practice, where she was intubated and given oxygen therapy. Thoracic radiographs were taken under sedation (acepromazine and butorphanol), and showed diffusely dilated oesophagus and aerophagia. The dog was allowed to recover, laryngeal paralysis was suspected and it was referred for assessment.

On clinical examination, the dog was quiet, alert and responsive, mucous membranes were pink and moist, pulses were good with no pulse deficits, heart rate (HR) was 150bpm, the rhythm was irregular, blood pressure (BP) measurement was normal and respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute. There was mild inspiratory stridor with mild increase in inspiratory effort.

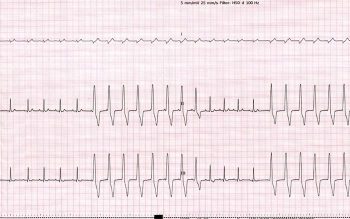

The arrhythmia raises some concerns and it is recommended to initially identify it using an ECG. The ECG showed an HR of 150bpm. The QRS complexes were wide and bizarre, and without an obvious preceding P-wave (Figure 1).

Due to the wide and bizarre morphology of the QRS complexes, they are likely to originate from the ventricles (ventricular ectopic complexes; VPCs). Another differential diagnosis for wide and bizarre QRS complexes would be a conduction disturbance (bundle branch block); however, this is not the case as no obvious P-waves were seen preceding the QRS complexes.

These ectopic complexes can either be VPCs or escape complexes (if they follow a pause). In this case, the ECG revealed runs of VPCs. As the HR was 150bpm this can be described as accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR).

The difference between ventricular tachycardia (VT) and AIVR is the HR. Ventricular tachycardia has a HR higher than 180bpm to 200bpm, and is usually associated with haemodynamic changes (such as reduced BP, poor quality pulses, weakness and syncope). VPCs may occur due to primary heart disease (such as cardiac neoplasia, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and endocarditis) or secondary to a systemic disorder (such as gastric dilation, pancreatitis, splenic masses, electrolyte imbalance and low blood oxygen saturation).

Further tests, such as comprehensive blood tests (haematology, biochemistry and electrolytes), thoracic radiographs, abdominal ultrasound and CT, can be considered to rule out non-cardiogenic causes of arrhythmias. An echocardiography should be considered to investigate a cardiac cause.

Following ECG, comprehensive blood tests (haematology, biochemistry, electrolytes and C-reactive protein) were performed and showed no significant abnormalities. An echocardiography was performed and myocardial disease was ruled out as the cause of the VPCs. Other systemic causes for VPCs needed to be ruled out and CT was elected with this purpose.

The dog was deemed safe to be anaesthetised – with the risks relating to the suspected laryngeal paralysis, megaoesophagus and arrhythmia. Emergency drugs were prepared before the anaesthesia was started.

At induction laryngeal paralysis grade four (paradoxical movements of both arytenoids present) was confirmed. A CT of the thorax did not show obvious pulmonary metastasis, and abdominal CT showed no obvious splenic masses or other sinister neoplasia. The patient was taken to theatre for left “tie-back” surgery.

If the arrhythmia is severe and left untreated, it may progress to ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest.

The recommended treatment is lidocaine bolus of 2mg/kg (can be repeated) and to continue with lidocaine constant rate infusion of 50µg/kg/min.

Alternative treatments include sotalol and amiodarone.

Treatment of the arrhythmia was not necessary as the dog was clinically stable. The most likely cause of VPCs in this case is myocardial hypoxia that occurred during the episode of syncope; however, a primary arrhythmia could not be completely ruled out. When the dog was assessed a week later, the VPCs resolved and thought most likely to be extracardiac in origin.

When encountering VPCs, it is important to investigate for cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic causes. Assess the severity of the VPCs (frequency, morphology, HR and BP) and treat accordingly. It is vital to be able to differentiate between VT and AIVR, as the first requires treatment, while the latter usually does not.