10 Nov 2021

The past 18 months have left veterinary teams across the country stretched to their limit. This has left many feeling depleted and burnt out, so should we be asking what we ourselves can do to help our own well-being?

Image © Good Studio / Adobe Stock

If we look at what the pandemic has brought – an increased workload with reduced resources; fear and anxiety about our health and the health of those we love; a lack of connection to our usual support networks; and a lack of opportunity for positive rest and decompression periods, such as foreign holidays and social gatherings – it is not surprising that we may be feeling that our well-being has suffered.

The pandemic has created the perfect storm for burnout and compassion fatigue in a profession that was already suffering. The question is, is there anything we can do to help ourselves?

The answer is yes and no. Burnout and compassion fatigue are functions of a workplace environment, and of teams within the workplace, and, while we can do things to help ourselves, changes are also required within the workplace and within the profession to effectively combat these problems.

An analogy I heard recently relates to the canary that was used in mine shafts to test the quality of the air. If the canary collapsed, reviving or treating it did nothing to alleviate the real problem of poor air quality. We didn’t blame the canary for collapsing or expend much effort trying to save it, but effort was made to improve the air quality. In the same way, to tackle burnout, improvements need to be made in the work environment and the profession – not just by individuals.

In terms of what we can do for ourselves, the best definition I have heard of self-care is “building a life for yourself that you don’t need to escape from”. It’s easier said than done.

Many of us have grown up with the expectation that we need to keep going; doing everything perfectly and meeting everyone else’s needs while abandoning our own. It’s not easy to change this ingrained behaviour – but it is possible with ongoing, daily practice.

Start by working on your boundaries, and really understanding what is okay for you and what isn’t. Is that extra shift you’re being asked to do actually okay? Or are you just saying yes because it’s easier than saying no? Don’t get me wrong, this can be difficult as you will annoy people, because it’s so much easier for them if you go along with what they want. But what is the cost to you long term? If you end up resentful, then disengaged, then burnt out, no one wins. You are responsible for deciding what is okay for you and then communicating this to others.

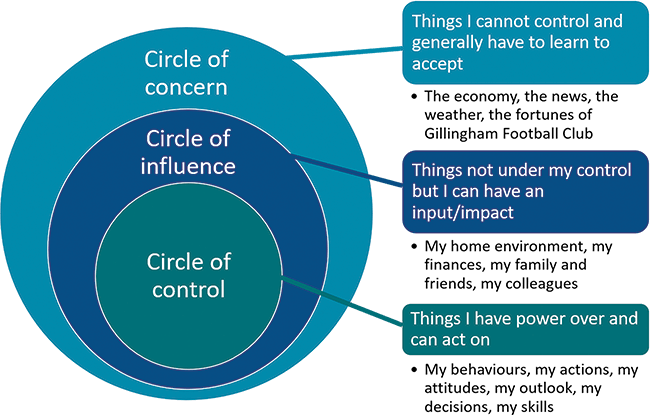

A useful tool in helping us to gain a bit more control when we are feeling overwhelmed is the circle of control and the circle of influence (below). It helps us to think about what our concerns are; what we can control and the areas in which we can start to exert influence.

No one is their best self when they feel out of control and overwhelmed, so using a tool like this can help us regain that balance and actually look at things that we are able to do to improve things for ourselves.

It is also helpful to explore your values and what drives you. In her book Dare to Lead, Brené Brown suggests refining them until you have just two core values, so that you can then make decisions based on them. If you have more than two, the danger is that none is truly important. Once you have identified your core values, ask yourself: “Does my workplace require me to live outside my values?” If it does, it will create an ongoing tension that will ultimately deplete your resources.

As an example, if one of my core values is honesty and I feel I’m being asked to hide things from clients, I’m constantly going to feel stressed and anxious. It’s essential to work in an environment that supports your values, whatever they are.

Rest and decompression are vitally important. Find things to do that make your heart sing and that speak to your creative side. They should invigorate you and replenish you, giving you the inner resources to return to the pressures of being a veterinary professional. Finding time in your day or week just to be still, reflect and think – whether this is by meditating, walking, reading or simply sitting – will give you space to decompress and reset.

Social interaction is also necessary for all of us and it is important to nurture our connections, whether at work with colleagues or outside with family and friends. We are a social species, and loneliness and isolation seriously impact our well-being.

As burnout and compassion fatigue are functions of workplaces and teams, it is important to review what can help at the workplace level. Burnout is caused by an imbalance between workload and resources. During the pandemic, many practices found the imbalance even more acute than usual, given an increased workload and reduced staffing.

Somehow, we have to tackle this at a time when recruitment seems to be near impossible. So, perhaps it is instead possible to reduce overall practice workloads. Could you utilise nursing teams more effectively? Develop good relationships with locums? In extreme cases, perhaps you could even close the books to new clients for a period of time? Reducing client numbers goes against our instincts, but if we don’t do anything to address workload issues in the short term, we will only experience more problems in the long term through staff disengagement, staff leaving and absences due to poor health, which will exacerbate the situation.

Burnout happens within teams – and it can be improved within teams. Building and fostering a strong team spirit is essential, as is developing a culture of positive feedback, in which regular recognition of the contribution of each member of the team is the norm.

Try to think creatively of ways that you can thank your team. Increasing positive feedback may be a good start? Do you need to offer more holiday? Or financial rewards? Or just try some simple things like bringing in cakes or other goodies once in a while?

Building time into your schedules to allow members of your team to reflect on their day and cases, whether formally or informally, helps – as does encouraging them to share their concerns. Just letting them know that they have done a good job helps to build resilience. Think about the spaces where your team take breaks. Are they relaxing? Do they enable connection with other team members? Do they offer an opportunity to enable team members to be on their own to reflect and decompress?

Team members who are playing to their strengths will be more fulfilled, calmer and more productive, so taking time to craft and adapt roles so that you are using the right people in the right place at the right time can pay dividends.

It requires you to really understand your teams and the individuals working within them. It involves listening to them, then working with them to make “the perfect” – or as near perfect as possible – job for them. This builds engagement and job satisfaction. It shows that you care.

Line managers need the skills to lead their teams effectively and some need specific training to help them do this. It’s worth exploring leadership programmes tailored for the veterinary sector, such as the recently launched Certificate in Veterinary Leadership and Management from the Veterinary Management Group (VMG).

This programme empowers leaders and managers to evaluate factors affecting their workplace culture, and support their staff better. It teaches them self-reflection and personal development planning skills, as well as helping them to learn how to listen actively; to recognise signs of mental unwellness within their team and to know what to do if they are worried about an individual.

The third level of activity needs to take place within the veterinary profession as a whole. Many of the individual skills of boundary setting, and knowing and living into our values, could be taught early in the education system – ideally at school, but definitely during vet school. Reflective learning is already taught and encouraged, and owners of veterinary businesses need more education as to how these behaviours can be embedded into the workplace.

The expectation that veterinary professionals will just keep going whatever demands are placed on them needs to start changing and those in leadership roles need to model the ability to set boundaries, rest and recuperate. Given that research for the VMG’s Leadership Standards showed that fewer than a quarter of veterinary leaders and managers reported that they visibly practise good well-being habits, such as taking breaks or eating lunch, in the workplace there is work to do in this area1.

Tough decisions need to be made about how we can limit workloads in a way that still fulfils our fundamental requirement of protecting animal welfare. No easy answers exist, but for the long-term benefit of the profession, we need to start thinking about solutions now.

Much can be done at an individual level to help us maintain our own well-being and each of us bears a responsibility to look after ourselves. This is not the whole answer, however.

Employers and the whole profession need to drive changes that will help to mitigate the effects of burnout and compassion fatigue, which have only been accelerated by the pandemic.

Lastly, and so importantly, we all need to recognise that burnout and compassion fatigue are reversible. The key is to take action at whatever levels you can.