10 Jul 2022

The global pandemic has significantly strained our mental health and well-being, affecting people’s work effectiveness, relationships with colleagues, and connections to their world. For business owners, prioritising your employees’ psychological and physical well-being produces improved retention, productivity, and a healthier workplace…

Image © AbsolutVision / Pixabay

Preaching to the converted and getting employees who are already interested in their health and well-being is not difficult for employers.

The challenge is engaging the non-engaged; employees who are less invested in the support that employers offer. Employers must master this engagement to ensure all their team is supported.

Resilience is a process of harnessing resources to sustain well-being. “Process” implies that resilience is not just an attribute or even a capacity; it is a dynamic experience of self-awareness and regulation. “Of harnessing resources” asks us to identify the most relevant resources to people in different environments and experiences.

“Sustained well-being” describes how resilience involves more than just a narrow definition of health or the absence of pathology.

How can you as an employer provide the resources that build your, and your team’s, resilience, and help the team manage its stress and anxiety?

These only provide extrinsic scaffolding for well-being to flourish, however. If we better understood the intrinsic causes of long-term anxiety and depression, we could structure a well-being strategy for ourselves, our families, and our teams. It may put the advice mentioned into a more helpful context for implementation.

Resilience is a skill we all need to develop, so include it in your broader people development programme. Train the team to recognise that resilience ebbs and flows, and isn’t simply something you do – or don’t – possess. A human brain in good working order has a tremendous capacity to learn and process information. Our self-regulation skills are vitally important for adapting to threats to human experience. Much resilience – especially in children – is embedded in connection and close relationships with others. Those relationships provide a profound sense of emotional security. Our workplace offers the opportunity to nurture similarly secure and beneficial relationships and friendships – and sometimes more – through shared values, purpose, achievements and culture.

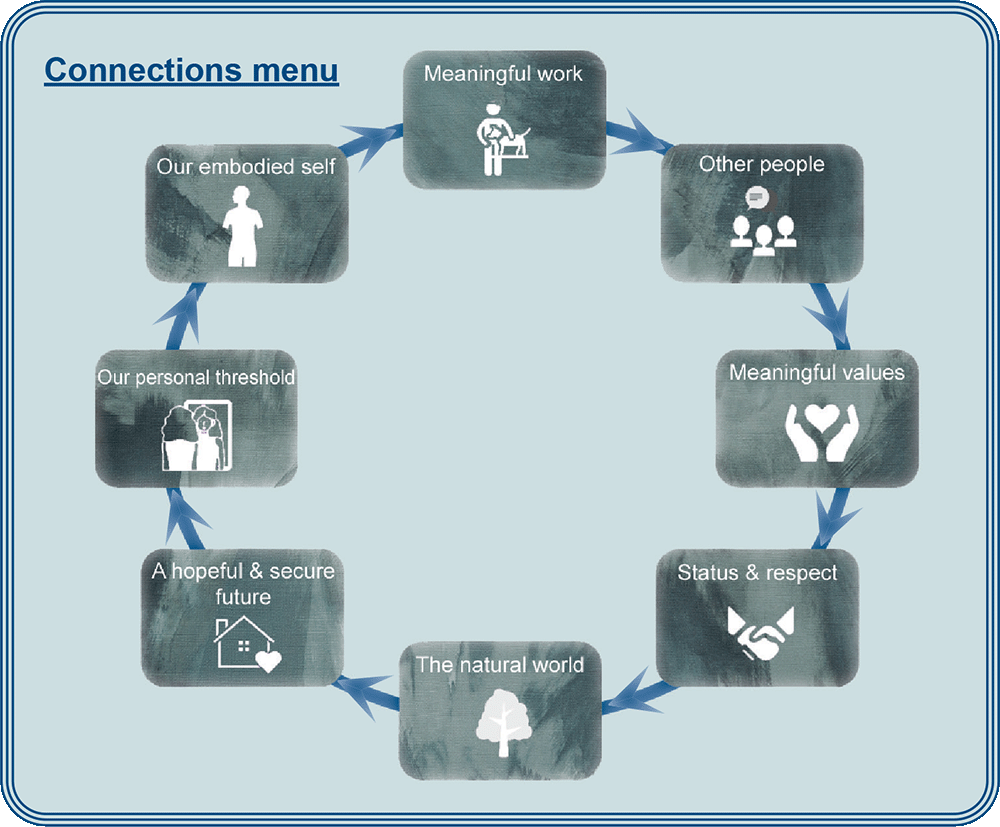

In Lost Connections, Johann Hari proposed some essential biological, psychological, and environmental lost connections that can lead individually and collectively to mental distress. He wrote this work well before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the resonances are stark, as they are salient to our “new” normal.

The disconnections he defines are:

Our ability to “listen to our pain and distress” raises two further intrinsic and personal disconnections.

Anxiety, therefore, is a body and brain challenge – our brain’s reading of our physical state, heart rate, breathing, CO2, everything. Everything our body does is in service of balancing bodily needs – oxygen, glucose, hormones or blood supply – to address predicted future needs. It adopts one of three modes built into our autonomic nervous system to do this.

The first, the ventral vagal parasympathetic system, is there to optimally regulate all your bodily systems – the “rest” and “digest” mode, which is the essence of well-being. It delivers feel-good chemicals, such as dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin, so you feel and perform at your best.

When we need to perform at a higher level, whether induced (exercise) or from threat, our second mode – the sympathetic nervous system; the “fight or flight” state – pumps out cortisol and epinephrine to enhance the action and increase focus. The body’s natural response to a perceived threat often includes increased blood flow, dilated pupils and a burst of energy. Anxiety is an impulse in our body that says: “I’m not safe right now”. It’s automatic, rapid, and unconscious.

Once the threat (or exercise) is gone, we should revert to the first well-being mode to recover and move on. However, when fight-flight proves ineffective (can’t fight, can’t flee) and this second stress mode prolongs, we exhaust our resources. We spiral into the third adaptive mode of the dorsal vagal parasympathetic system of mental and physical survival. We freeze. We shut down. We experience depression and burnout, releasing endorphins and reducing pain and activity. Once here, it is tough to return.

Our capacity to maintain a dynamic balance between the first (parasympathetic) and second (sympathetic) mode is called homeostasis. It determines our well-being and quality of life, a skill we need to hone to prevent physiological lockdown.

Consider the effects of social media, politics, money, child care, climate change, Covid, work stress and family drama. It is easy to see why anxiety is the most common mental illness today, affecting almost 20 per cent of the population. Humanity today, in basic terms, could be described as freaked-out Neanderthals living in fight-or-flight mode 24/7.

Notably, during a defensive response, the neocortex – our thinking brain – is the last to be aware that something is wrong, and doesn’t get to decide whether we’re stressed or feeling threatened or challenged.

Stress arousal and emotions belong to the limbic and autonomic survival brain. So, if you want to track your anxiety, your body – not your thoughts – provides the most reliable compass.

Achieving connection to our embodied selves by establishing a felt sense of safety within the body, we gain a second strategy for personal decompression: increasing our innate physiological resilience.

All this takes practice.

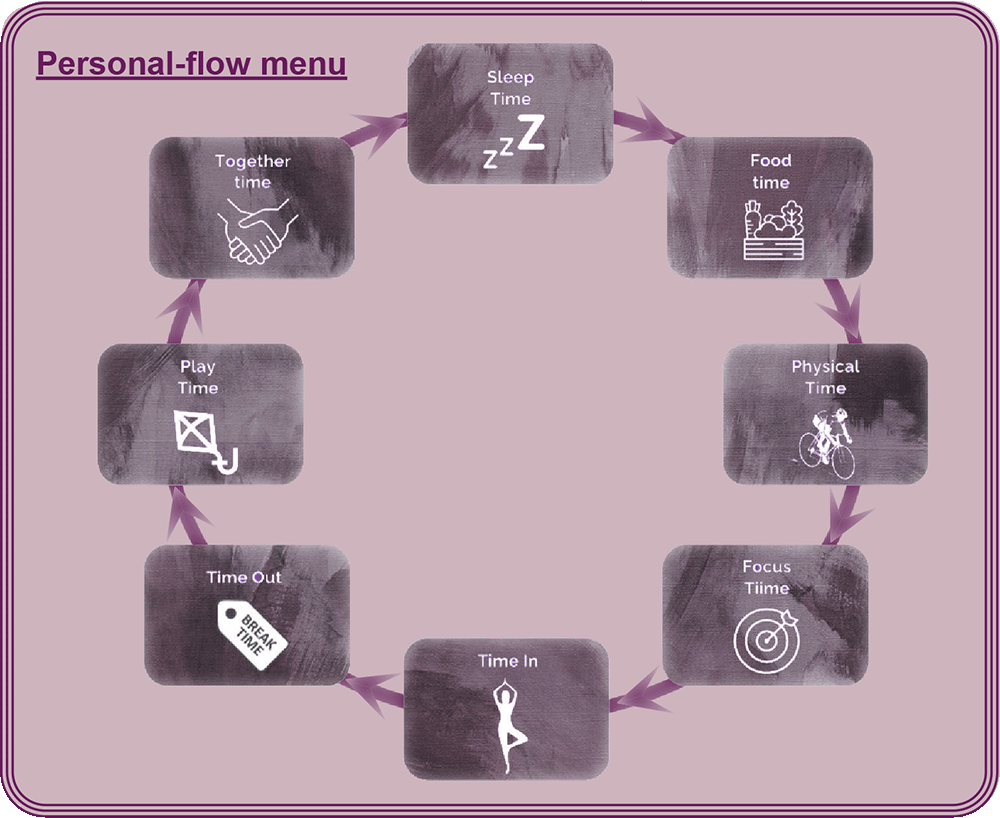

Here are eight daily practices to share with your team to help reduce anxiety and improve mood, resilience, and well-being:

No certainty is in sight, which is stressful. But there will be a future, and we will flourish again – if we choose well-being.

Find exciting ways to thrive, seek calm often, and support each other – we’re in this together, after all. Above all, stay connected.