16 Sept 2025

Continuous mapping of efficient calf shed environment parameters

George Lindley BVetMed, PGDip(VCP), MVetMed, DipECBHM, MRCVS and Sophie Mahendran BVM, BVS, DipECBHM, PGCert Vet Ed, MSc, VetEpi & Public Health, PhD, MRCVS discuss some of the topics around shed design they will cover in their session at BCVA Congress.

Figure 1. Image of a very large A-frame shed being used to house calves. This is a massive air space, with a very exposed and open end, offering little protection from winter conditions outside. The addition of gale breakers or other cladding to the open end of the shed would improve the level of protection offered to the calves.

Efficient calf rearing to optimise health and growth is critical to ensure youngstock develop to reach their full potential, whether that be as dairy replacements or for beef production.

While clear and concise guidelines on some aspects of calf care, such as colostrum management, are largely applicable to all types of farms, guidance around the environment within which a calf lives are much more complicated due to the wide range of housing designs and geographical factors found on farms.

The UK is described as having a temperate climate, featuring cool wet winters and warm wet summers. Typical mean winter and summer temperatures around 3.5°C and 15.3°C respectively, with wide ranges resulting in highly variable conditions depending on the season.

Individual calf housing has reduced in popularity, with only 38.4% of farms utilising it (Mahendran et al, 2022), likely due to policy changes by milk buyers driven by a better understanding of the importance of social housing for calves.

Many farms now use calf sheds, which can be thought of as permanent structures, usually an A-frame (Figure 1) or monopitch in design, that generally give a large air space containing many calves. Many of these sheds rely on natural ventilation, but they often have inadequate inlet and outlet areas along with adjoining to other livestock buildings, which further impedes air flow (Brown et al, 2021). This poor ventilation is linked to respiratory disease (Callan and Garry, 2002), with stale air enhancing viral pathogen survival, and when combined with high humidity this can increase transmission rates among calves in a shared airspace (Mars et al, 1999).

What can we measure?

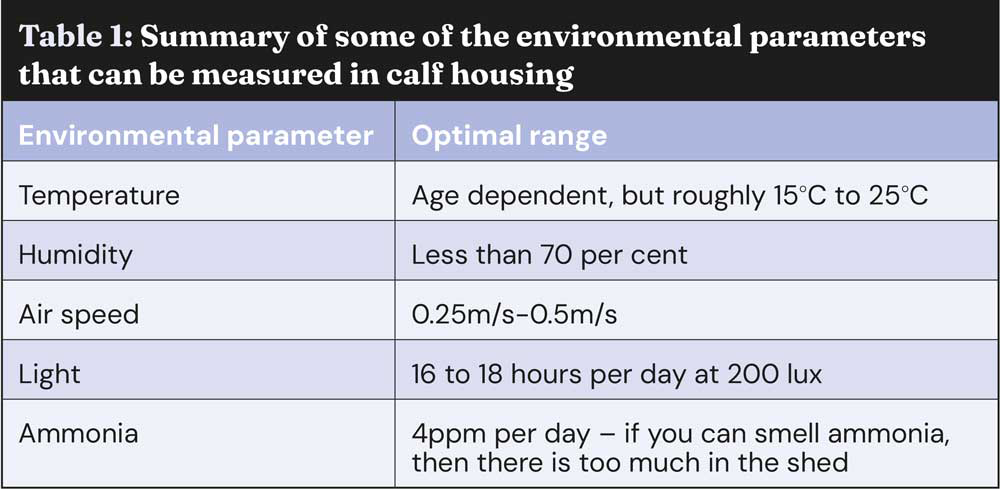

Multiple physical parameters can impact the environment and, specifically, air quality that a calf is exposed to; temperature, humidity, air speed, particulate matter and other airborne compounds, such as ammonia and microorganisms (Table 1).

Temperature

The thermo-neutral zone of a calf up to three weeks old is 15°C to 25°C (Stull and Reynolds, 2008), with the UK experiencing these temperatures for up to nine months of the year.

Below the thermo-neutral zone calves must utilise energy through metabolic heat production to maintain their core body temperature by skeletal muscle contraction (shivering) or by non-thermogenic processes, such as increasing energy intakes (Bell et al, 2021).

Conversely, calves in the UK are now experiencing heat stress in the summer periods (Mahendran et al, 2023), with respiratory rates and rectal temperatures starting to increase at temperatures as low as 21°C (Dado-Senn et al, 2023).

These two environmental extremes often mean that calf housing that works well at one time of year often doesn’t work so well at others.

Air speed can have a vital role in the temperature experienced by a calf, with the requirement varying depending on the external temperatures.

Cold calves require protection from draughts (Figure 2), whereas hot calves can be effectively cooled by increasing air speeds at calf level during hot times of the day in the summer.

Air movement is also important for fly control in the summer months, with flies disliking areas of constant air movement.

Humidity

Relative humidity is a measure of the actual moisture content of the air, with the target level in a calf shed considered to be lower than 70%. High humidity levels result in more condensation on the walls and roof of a building, as well as on the coat of the calves, which decreases their hair insulating properties (Anderson and Bates, 1979), and is associated with lung inflammation and respiratory disease (van Leenen et al, 2020).

Complete control of humidity is only possible with fully enclosed housing, and in naturally ventilated barns the humidity can only be managed by ensuring good ventilation. While humidity is linked to environmental moisture levels, the impact of fluid management within a shed should not be overlooked, with good drainage needed to remove urine and faeces as well as the spillage of water and milk on to the floor.

Particulate matter and ammonia

Calves are exposed to inhalable particles (dust) that can be deposited in the upper airways (Peña Fernández et al, 2019), with small particle sizes smaller or equal to 10µm in diameter being able to travel deep into the lungs and incite respiratory tract irritation and an increased risk of respiratory disease due to pathogen transfer (Urso et al, 2021).

Dust levels in housing varies throughout the day, with peaks associated with increased animal activity and the process of providing fresh bedding (van Leenen et al, 2020). In addition to dust, bedding fermentation can produce ammonia (Maeda and Matsuda, 1998), with high levels linked to increased odds of suffering from severe lung consolidation and increased lung fluid neutrophil levels (van Leenen et al, 2021). In addition, farm workers are also at potential risk, with prolonged exposure to ammonia contributing to human diseases such as bronchitis and occupational asthma.

How do we measure what is happening in calf housing?

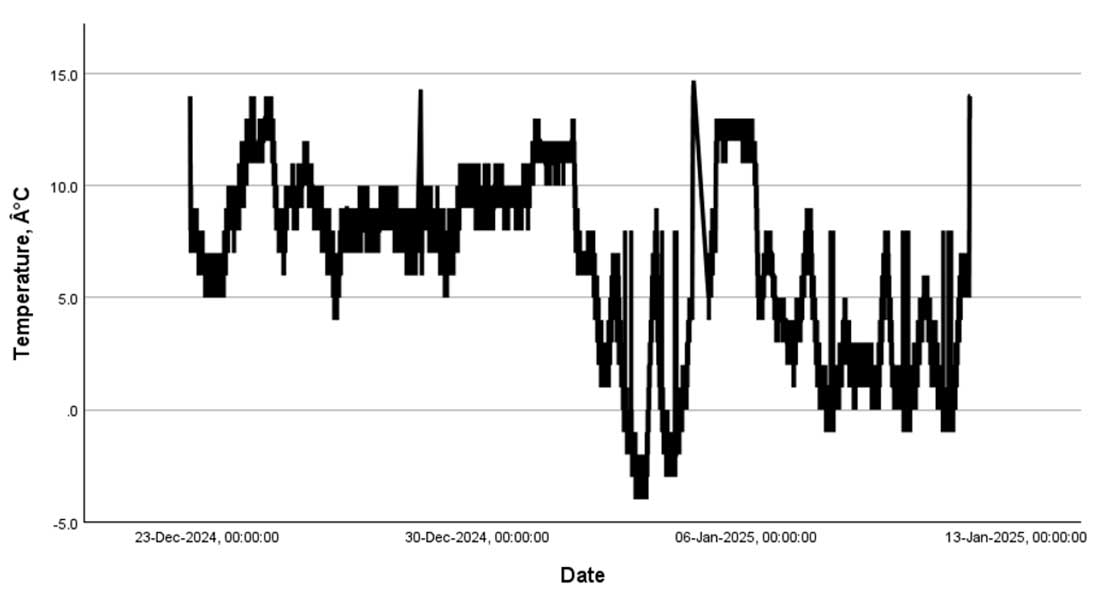

Utilising technology allows continuous monitoring of temperature and humidity within a shed to establish day-to-day variability. Data loggers can be purchased relatively cheaply, allowing data to be downloaded and graphs to be made to aid in simple interpretation (Figure 3).

Smoke bombs are great for visually demonstrating the air currents within a shed, and how effective the inlets and outlets are at creating appropriate circulation and speeds (Figure 4).

Conclusion

As the old saying goes, you don’t know what is happening unless you measure it – the calf shed environment is no different, and can have a critical influence on the health and well-being of the calves living within it.

Reassessing these parameters throughout the year is important as the weather changes, switching from cold stress to heat stress conditions. This will often mean changes need to be made on a seasonal basis, through the movement of cladding to the increase or decrease in air entry, and alterations to the level of acceptable air speeds.

- This article appeared in Vet Times Livestock (Autumn 2025), Volume 11, Issue 3, Pages 6-7

- The subject this article was based on was due to be presented at BCVA Congress on 9 October 2025.

- Bovine respiratory disease: focus on getting the environment right – five key questions veterinarians can use to assess calf housing in this article from the Vet Times archive.

Authors

George Lindley graduated from the RVC in 2017. He completed a residency in production animal health and became a diplomate of the European College of Bovine Health Management in 2022. He is currently a final-year PhD student studying calf health and immunity at the RVC.

Sophie Mahendran graduated in 2012 and went on to complete an internship and residency programme in production animal medicine. She became a diplomate of the European College of Bovine Health Management in 2019, and went on to complete her PhD in calf health at the RVC in 2024.

References

- Anderson JF and Bates DW (1979). Influence of improved ventilation on health of confined cattle, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 174(6): 577-580.

- Bell DJ, Robertson J, Macrae AI, Jennings A, Mason CS and Haskell MJ (2021). The effect of the climatic housing environment on the growth of dairy-bred calves in the first month of life on a Scottish farm, Animals (Basel) 11(9): 2,516.

- Brown AJ, Scoley G, O’Connell N, Robertson J, Browne A and Morrison S (2021). Pre-weaned calf rearing on Northern Irish dairy farms: part 1. A description of calf management and housing design, Animals (Basel) 11(7): 1,954.

- Callan RJ and Garry FB (2002). Biosecurity and bovine respiratory disease. In Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 18(1): 57-77.

- Dado-Senn B, Van Os J, Dorea J and Laporta J (2023). Actively ventilating calf hutches using solar-powered fans: Effects on hutch microclimate and calf thermoregulation, JDS Communications 5(1): 61-66.

- Maeda T and Matsuda J (1998). Ammonia emissions from composting livestock manure 1: Factors affecting ammonia emissions, Journal of the Japanese Society of Agricultural Machinery 60(6): 63-70.

- Mahendran SA, Wathes DC, Booth RE and Blackie N (2022). A survey of calf management practices and farmer perceptions of calf housing in UK dairy herds, Journal of Dairy Science 105(1), 409-423.

- Mars MH, Bruschke CJMM and Van Oirschot JT (1999). Airborne transmission of BHV1, BRSV, and BVDV among cattle is possible under experimental conditions, Veterinary Microbiology 66(3): 197–207.

- Peña Fernández A, Demmers TGM, Tong Q, Youssef A, Norton T, Vranken E and Berckmans D (2019). Real-time modelling of indoor particulate matter concentration in poultry houses using broiler activity and ventilation rate, Biosystems Engineering 187: 214-225.

- Stull C and Reynolds J (2008). Calf welfare, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 24(1): 191-203.

- Urso PM, Turgeon A, Ribeiro FRB, Smith ZK and Johnson BJ (2021). Review: the effects of dust on feedlot health and production of beef cattle, Journal of Applied Animal Research 49(1): 133-138.

- van Leenen K, Jouret J, Demeyer P, Van Driessche L, De Cremer L, Masmeijer C, Boyen F, Deprez P and Pardon B (2020). Associations of barn air quality parameters with ultrasonographic lung lesions, airway inflammation and infection in group-housed calves, Preventive Veterinary Medicine 181: 105056.

- van Leenen K, Jouret J, Demeyer P, Vermeir P, Leenknecht D, Van Driessche L, De Cremer L, Masmeijer C, Boyen F, Deprez P, Cox E, Devriendt B and Pardon B (2021). Particulate matter and airborne endotoxin concentration in calf barns and their association with lung consolidation, inflammation, and infection, Journal of Dairy Science 104(5): 5,932-5,947.