22 Jul 2025

Foot trimming: focus on five steps

Sara Pedersen BSc, BVetMed, CertCHP, DBR, MRCVS and Andrew Tyler NPTC L3, Dutch Diploma explain the importance of hoof trimming in the ongoing management of lameness – and vets following key stages

Measuring the claw is the focus of the first of five steps.

Routine, preventive hoof trimming is a key cornerstone of lameness management in the dairy herd, with the vast majority of dairy farmers implementing it to some degree as part of their lameness management (Pedersen et al, 2022). However, it also has the potential to be a cause of lameness if implemented incorrectly.

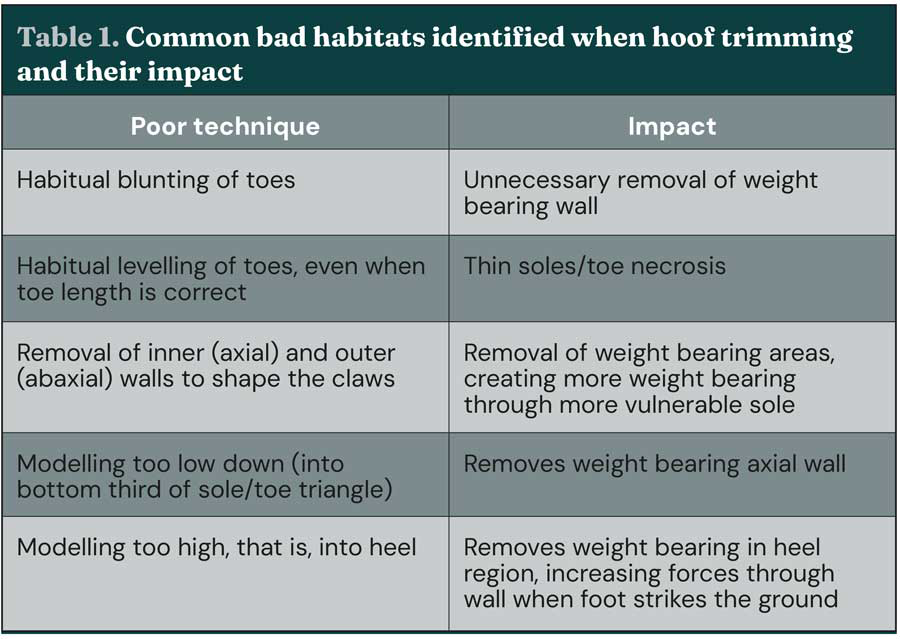

In comparison to other areas of dairy cattle health and welfare, hoof trimming has received less attention and, as a result, relatively fewer robust studies are available in this area by comparison. Wherever a gap in evidence exists, it is often filled with opinion, a divergence in techniques and a subsequent loss of standards. Confirmation bias and subjectivity can then lead to these new ideas becoming ingrained and a dangerous situation created where the abnormal becomes normal as bad practices become habitual (Table 1). Ultimately, this can lead to poorer outcomes from preventive hoof trimming at the detriment to the cow’s welfare.

Focusing on aims and objectives

The aim of hoof trimming is to either reduce future lameness risk if the cow is sound, or, if she is lame, to resolve this as quickly as possible.

Therefore, every aspect of the approach to hoof trimming must benefit, and not be to the detriment of, these aims.

In turn, this comes back to function and not appearance – a functional trim may not necessarily be the most visually pleasing, but it is function and not appearance that will keep a cow sound.

Five-step method

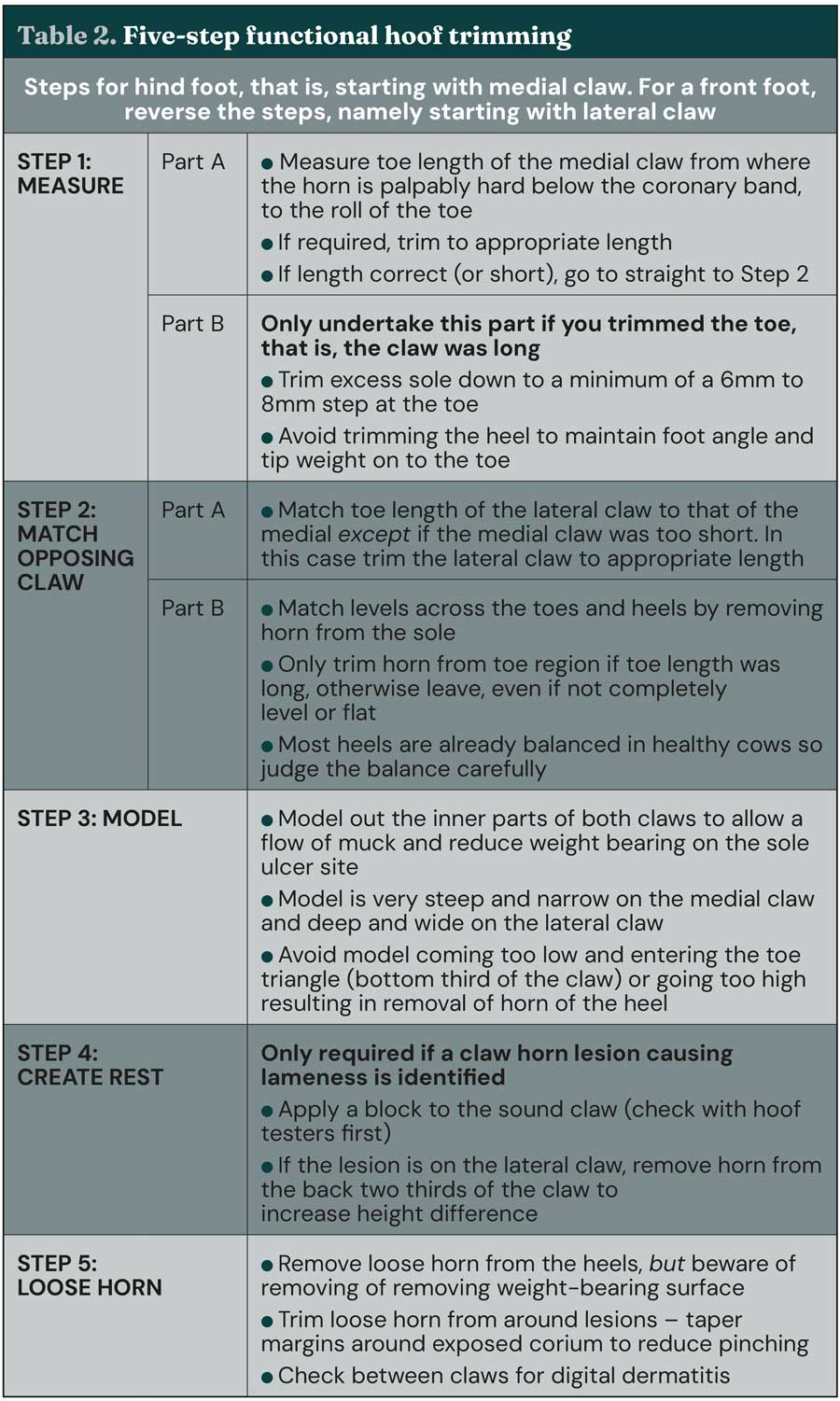

While the original “Dutch” five-step method provided a sound approach, as with any method we need to update and modernise in line with emerging evidence. Four decades ago, when Toussaint Raven introduced the Dutch five-step method, it was designed for the smaller, lower-yielding Friesian cow, which was predominantly grazed. However, our modern Holstein cows and housed systems are vastly different. Therefore, while the fundamental approach to the foot remains, these have been updated according to the available evidence (Table 2).

The first three steps apply to functional trimming, that is, improving foot shape to reduce future risk of lameness, whereas steps four and five relate to therapeutic trimming and a response to an identified problem. Regardless of the reason for a cow being inspected or whether a problem is immediately obvious, it is important to follow the steps.

Step one: measure (applies to medial claw of a hind foot or lateral claw of a front foot)

Part a. Assessing dorsal wall length and trimming to length (if required)

The original Toussaint Raven method states the dorsal wall of the medial claw should be cut to “a good 7.5cm for an adult Friesian cow”, although the proximal landmark for the measurement is not defined in the published description of the technique. However, this is too short for most cows today and trimming to this length will result in overtrimming.

Validation of the most appropriate proximal landmark to use indicates this is when the horn becomes palpably hard below the coronary band (Pedersen et al, 2019). Note that this is not on the coronary band itself and that the distance between the coronary band and the point at which the horn is palpably hard varies between individual cows.

Only if the dorsal wall length is greater than the recommended length of the cow’s breed and age (Table 3) should it be trimmed to length. If it is already at the correct length (or shorter), then step one is complete.

Part b. Levelling (or stabilising the sole)

Maintaining sole thickness is absolutely vital to avoid overtrimming, as risk of lameness increases as sole thickness decreases (Griffiths et al, 2024). Habitual levelling of the soles is a major contributor to thin soles. Dorsal wall length is a guide to how thick the sole is, hence when toe length is correct (or short), the sole should not be touched. Where the toe is shortened to the correct length, the step created can provide a guide as to the sole thickness at the toe.

The sole can then be levelled to reduce sole thickness at the toe to a minimum of 6mm to 8mm. However, always err on the side of caution. Care must be taken to not remove horn from the heel area to maintain foot angle and tip weight into the toe region.

Step two: match (applies to lateral claw of the hind claw and medial claw of the front foot)

This step involves matching the length of the partner claw to the claw trimmed in step one, as well as balancing them at the heels. However, in the event that the claw in step one was short, this does not apply, and instead the partner claw should be measured and trimmed to appropriate length.

In most healthy cows the heels will already be balanced and so this element of step two is not required, and balance should be carefully assessed before any horn removal. Again, if the claw is the correct length, the sole in the toe region should not be trimmed, even if it is not level.

Step three: model

The purpose of this step is to allow muck to spread more freely between the claw, although the main benefit comes from relieving of weight bearing in the sole ulcer site of the lateral hind claw.

While the model on the medial hind (or lateral front) claw is very steep and narrow to maximise stability and weight bearing on the claw, the model in the lateral hind (or medial front) is deep and wide – coming out to (but not encroaching on) the white line.

This enables a deeper model to be incorporated that creates more “rest” in the sole ulcer site. Essentially, this means an increased length of time before weight bearing in this area, leading to a reduced risk of claw horn lesions (Sadiq et al, 2021; Stoddard et al, Pedersen et al, 2024).

Step four: rest painful claw (if claw horn lesion identified)

When a painful claw horn lesion is identified, a block should be applied to the partner claw. Where the lesion is at the rear of the hind lateral or front medial claw, horn should be removed from the back two thirds of the claw to increase the achieved height difference.

When treating early cases of lameness, benefit can also be seen in administering three days of NSAIDs to improve recovery rates (Thomas et al, 2015).

Hoof testers can be used to aid in identifying whether a lesion is painful, alongside the cow’s mobility score. They should also be used to check for pain in a claw before applying a block. Their use is not recommended routinely in sound cows due to the high chance of false positives and, therefore, unnecessary treatments being implemented.

Step five: remove loose horn

Where heel horn erosion is present, this should be removed. However, it is important not to compromise the weight-bearing areas in doing so.

This step also includes the removal of loose horn around lesions, which is a crucial step to promote healing and reduce the risk of material being trapped in any pockets that may exacerbate a lesion.

The horn should be trimmed back to the margin of attachment and tapered/thinned around areas of exposed corium to reduce pinching and enhance healing.

Conclusion

The five steps provide an easy-to-follow approach to a foot, regardless of whether it is being inspected for preventive or therapeutic purposes.

However, as with any method, it needs to be updated alongside the publication of new evidence and, most of all, needs to be implemented correctly to ensure that the outcome is beneficial, rather than detrimental.

- This article appeared in Vet Times Livestock (Summer 2025), Volume 11, Issue 2, Pages 10-12

- Another article from the same author – Lameness detection: the weakest link – is available in our clinical archive.

Authors

Sara Pedersen graduated from the RVC in 2005, and has since worked exclusively with farm animals – predominantly dairy cattle. She is an RCVS specialist in cattle health and production and runs Farm Dynamics, a consultancy business involved in research, training and teaching at a number of vet schools. She is also a member of the Wales Animal Health and Welfare Framework Group and BVA’s Welsh branch.

Andrew Tyler is a fully qualified professional hoof trimmer and has been an instructor and assessor for nearly 20 years. He works as part of a vet-led team with Aberteifi Farm Vets in Cardigan, west Wales, where he is also involved in hoof trimming training and teaching at Aberystwyth School of Veterinary Science.

References

- Griffiths BE, Barden M, Anagnostopoulos A, Bedford C, Higgins H, Psifidi A, Banos G and Oikonomou G (2024). A prospective cohort study examining the association of claw anatomy and sole temperature with the development of claw horn disruption lesions in dairy cattle, J Dairy Sci 107(4): 2,483-2,498.

- Pedersen SIL, Hudson CD, Bell NJ, Huxley JN and Green MJ (2019). Predicting sole thickness, which measurements are best? Total Dairy Seminar, Stratford-upon-Avon.

- Pedersen SIL, Huxley JN, Hudson CD, Green MJ and Bell NJ (2022). Preventive hoof trimming in dairy cattle: determining current practices and identifying future research areas, Vet Rec 190(5): e1267.

- Pedersen SIL, Hudson CD, Bell NJ and Green MJ (2024). Preliminary results from a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effect of foot trimming technique before first calving on the risk of claw horn lesions in early lactation, Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium and 14th International Conference on Lameness in Ruminants, 16-20 September 2024, Venice: 150-151.

- Sadiq MB, Ramanonn SZ, Shaik Mossadeq WM, Mansor R and Syed-Hussain SS (2021). A modified functional hoof trimming technique reduces the risk of lameness and hoof lesion prevalence in housed dairy cattle, Prev Vet Med 195: 105463.

- Stoddard G, Cook N, Wagner S, Solano L, Shepley E and Cramer G (2025). A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of 2 hoof trimming methods at dry-off on hoof lesion and lameness occurrence in dairy cattle, J Dairy Sci 108(5): 5,244-5,256

- Thomas HJ, Miguel-Pacheco GG, Bollard NJ, Archer SC, Bell NJ, Mason C, Maxwell OJR, Remnant JG, Sleeman P, Whay HR and Huxley JN (2015). Evaluation of treatments for claw horn lesions in dairy cows in a randomised control trial, J Dairy Sci 98(7): 4,477-4,486.