29 Apr 2025

Lameness detection: the weakest link

Sara Pedersen BSc, BVetMed, CertCHP, DBR, MRCVS explains how professionals can spot the early signs and teach clients to spot them, too.

Image: smspsy / Adobe Stock

Over the past decade, our knowledge and understanding of lameness in dairy cattle has expanded rapidly.

We have a better understanding of the importance of early detection and have seen a shift in focus away from antimicrobial treatments in favour of administration of NSAIDs based on an increasingly robust evidence base.

However, despite our increasing knowledge, many barriers still remain in engaging farmers in lameness management.

Underpinning these is a failure to recognise lameness. Put simply, you cannot tackle what you cannot see.

Recognising lameness

The research is very clear: we need to detect cows early in their course of lameness to realise the benefits of best practice treatment. A delay of a few weeks results in a significant reduction in recovery rates (Thomas et al, 2016).

This is why the mantra of early detection and prompt effective treatment (EDPET) is so important; little benefit exists to treating promptly and effectively if lameness is detected too late.

While every farm will undertake lameness detection to some degree as part of normal daily activities, this must be differentiated from active surveillance for early cases through regular mobility scoring. The subtle behavioural indicators of an early case of lameness are difficult to spot unless time is set aside purely for this task.

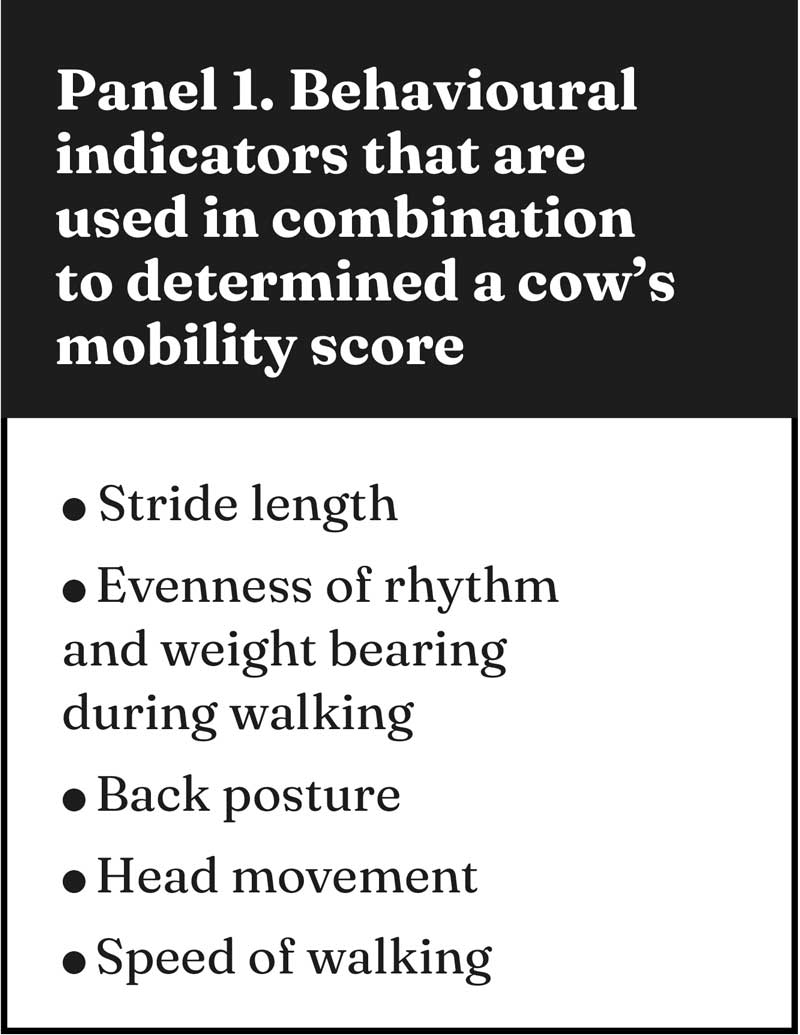

A number of behavioural indicators are used in combination to determine a cow’s mobility score (Panel 1), based on the original research of O’Callaghan et al (2003). They sought to determine which behavioural indicators, or combination thereof, were most likely to be present in cows that had foot lesions; that is, a cow that is likely to benefit from treatment.

Stride length

A sound cow (score 0) should take long, fluid, even strides. The position of the udder means that a cow will not always necessarily track up (Figure 1); that is, her back feet will not always land in the same position as the front feet were placed.

However, comparing stride length between the legs can indicate which limb is painful; for example, a cow may take a shortened stride on her painful leg, resulting in her contralateral leg swinging through more quickly to take the weight off the painful leg.

Evenness of rhythm and weight bearing

A cow should be confident bearing weight through each limb and walk with an even rhythm. She should not have any shortened strides, and all limbs should move at the same speed.

A useful way to assess weight bearing is to focus on the movement of the dew claws. The dew claws on each leg should drop evenly and fluidly; however, where some pain is present during weight bearing, this can result in the foot appearing “stiff”, with a lack of flexion in the pastern joint.

As a result, the dew claws do not drop as far as they would do if no pain was present (Figure 2).

This is a good early indicator of lameness and very helpful to use when adopting successful EDPET.

Back posture

Cows with good mobility (score 0) will walk with a flat back; however, those with impaired mobility may potentially walk with an arched back, depending on the severity and duration of lameness. Often, cows with early signs of lameness will have a flat back.

Head carriage and movement

A sound cow will typically walk with her head up as she is confident in where she places her feet, whereas a cow with impaired mobility may carry her head lower as it is more cautious of where she places her feet.

A cow with pain in her front leg will often “lift” or “bob” her head as she bears weight (Figure 3); however, a cow with hindlimb pain may nod her head as it bears weight on that limb.

Speed of walking

Speed can be a useful indicator of the severity of the mobility impairment. Those with severely impaired mobility (score 3) will be unable to keep up with sound cows and will often stop and pause when walking over a longer distance.

However, when speed is taken into account when assigning a score, it should be noted that the cow’s speed should be related to lameness issues rather than other reasons for her low walking speed, such as illness, age or a docile nature.

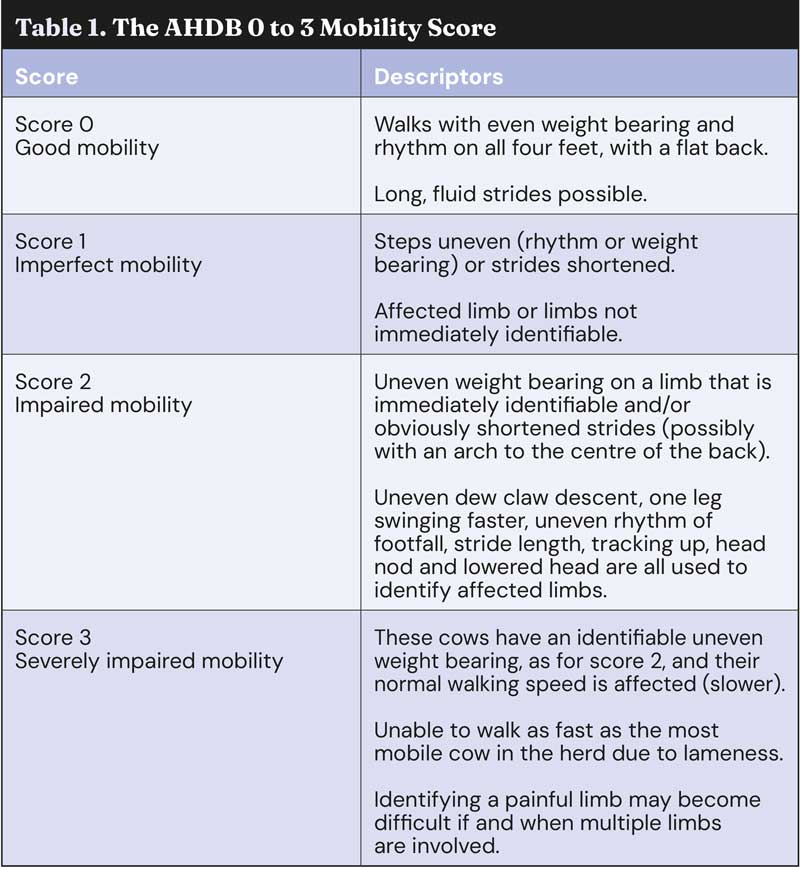

When mobility scoring, these behavioural indicators are used to help assign the cow a score based on the AHDB 0 to 3 mobility score (Table 1).

It is important to remember that when watching a cow, we are looking for consistent abnormalities in her gait, and this means that cows should be watched for around 8 to 10 strides; for example, a cow that takes one to two shortened strides out of the 10 is unlikely to be lame; however, a cow that repeatedly and consistently takes a shortened stride on one leg is likely to be lame and benefit from inspection.

Benefits of early detection

Earlier detection leads to higher recovery rates and a reduced chance of chronicity, which overall leads to reduced lameness prevalence in the herd.

The best practice approach to claw horn lesions (sole bruising, sole ulcer and white line disease) is to undertake a therapeutic trim, apply a block to the partner claw (if sound) and administer NSAIDs. Following this approach, when detected at an early stage of lameness, it is expected that 85 per cent of cows will be non-lame five weeks later (score 0 or 1), compared to just 16 per cent if detected at a later stage (Thomas et al, 2015; 2016).

Once a cow goes lame, she is predisposed to repeated cases of lameness for life. It is these cows with a history of lameness that are the key drivers of lameness prevalence on farm and contribute significantly to the number of lameness treatments undertaken (Randall et al, 2018).

Repeated lameness events (or history of claw horn lesions) are associated with a reduced digital cushion volume, which then further increases the risk of lameness (Wilson et al, 2021). This chronicity cycle is difficult to reverse; therefore, this reinforces the benefits of EDPET due to its reduction in repeat lameness events and, ultimately, cows with little hope of recovery.

Summary

Despite the proven benefits of early detection through mobility scoring, and NSAIDs in the treatment of lameness, the uptake of these on farm is still very low.

Very few measures can be implemented across all farms regardless of management system; however, EDPET is one of these.

Therefore, it is important that farmers are engaged more in discussions around the benefits of its implementation on farm.

Raising awareness of the signs of early lameness is a vital first step as without recognition, action will not follow.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 17, Pages 6-8

- An updated article – Foot trimming: focus on five steps – is available here.

References

- O’Callaghan KA, Cripps PJ, Downham DY and Murray RD (2003). Subjective and objective assessment of pain and discomfort due to lameness in dairy cattle, Animal Welfare 12(4): 605-610.

- Randall LV, Green MJ and Huxley J (2018). Use of statistical modelling to investigate the pathogenesis of claw horn disruption lesions in dairy cattle, The Veterinary Journal 238: 41-48.

- Thomas HJ, Miguel-Pacheco GG, Bollard NJ, Archer SC, Bell NJ, Mason C, Maxwell OJR, Remnant JG, Sleeman P, Whay HR and Huxley JN (2015). Evaluation of treatments for claw horn lesions in dairy cows in a randomised control trial, Journal of Dairy Science 98(7): 4,477-4,486.

- Thomas HJ, Remnant JG, Bollard NJ, Burrows A, Whay HR, Bell NJ, Mason C and Huxley JN (2016). Recovery of chronically lame dairy cow following treatment for claw horn lesions: a randomised controlled trial, Veterinary Record 178(5): 116.

- Wilson JP, Randall LV, Green MJ, Rutland CS, Bradley CR, Ferguson HJ, Bagnall A and Huxley JN (2021). A history of lameness and body condition score is associated with reduced digital cushion volume, measured by magnetic resonance imaging, in dairy cattle, Journal of Dairy Science 104(6): 7,026-7,038.