2 Sept 2025

Gastrointestinal issues: who is giving out advice – and is it right?

Nicola Lakeman MSc, BSc(Hons), CertSAN, CertVNECC, VTS(Nutrition), RVN, discusses issues around gut upsets and diarrhoea, and how practices – and their nurses –can help cats and dogs get better.

Image: anastas_ / Adobe Stock

Estimates indicate that 8.18% of all cases seen in primary first opinion practices involve animals presenting with acute, self-limiting diarrhoea (O’Neill et al, 2025).

These figures only include those seen in practice for a consultation and do not include those who contact the practice for advice or self treat at home. Advice given at practices varies greatly, but should be backed by science with supporting research evidence.

Diarrhoea in dogs and cats can be caused by specific pathogens, polymicrobial interactions or due to shifts or imbalances in the microbiome in response to external stress (Bell et al, 2008).

Usually, the cause will remain unknown, as the animal will often spontaneously recover (Herstad et al, 2010). Self-limiting symptoms are commonly relieved with a healthy diet or over-the-counter (OTC) products (Garcia-Mazcorro et al, 2017), with a large proportion of animals not being presented to veterinary practice.

Antimicrobial drugs and probiotics are frequently administered in the treatment and management of acute diarrhoea (Shmalberg et al, 2019), to influence the gastrointestinal microbiome and shorten the time to clinical resolution (Armstrong, 2013; Jugan et al, 2017).

The administration of antimicrobials has raised concerns about the efficacy of them and the development of antimicrobial resistance. An RCVS knowledge summary examined the role of metronidazole in the treatment of acute diarrhoea. It was concluded that no evidence-based rationale existed for its use in cases of uncomplicated, acute canine diarrhoea compared to supportive measures alone (Rogers-Smith, 2021). Supportive measures stated included nutrition, probiotics and synbiotics, while maintaining hydration of the individual.

What advice are we giving in practice?

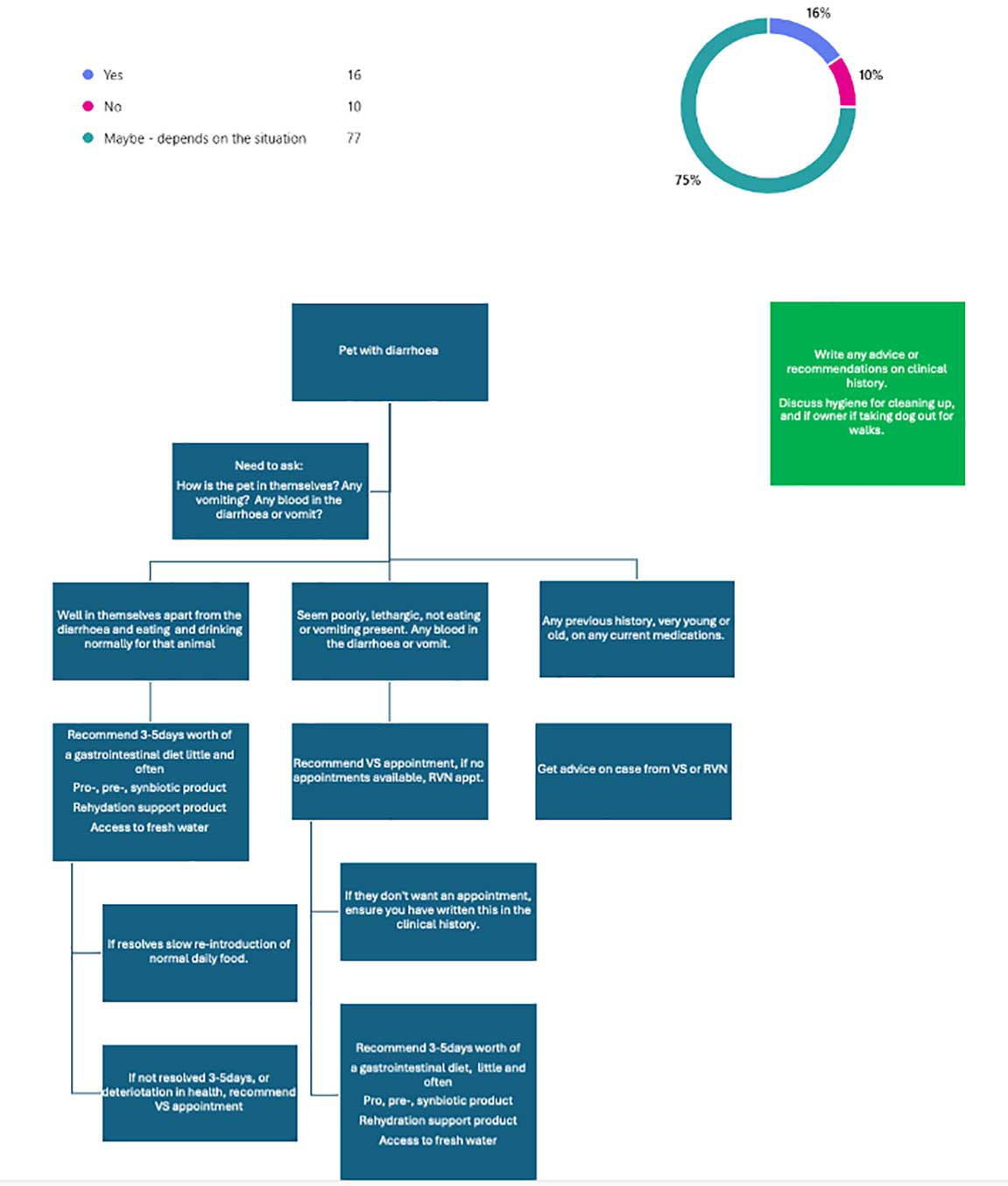

Traditionally, owners would phone practices asking for advice for their pet that has diarrhoea. In a recent survey, only 10% of practices would not permit non-clinically qualified staff to give health care advice; others (90%) were happy with staff giving out pre-approved information, depending on the situation. This highlights the importance of training and guidance for our practice support staff.

Figure 1 is an example of a flow chart or decision tree that can be used by practices.

Clinical significance

Animals with acute onset diarrhoea had better clinical outcomes when administered a probiotic or synbiotic than those that did not (Tong, 2019). This is also supported by another RCVS knowledge summary (Tong, 2019).

In those cases that do not resolve, a three-day pooled sample is advised for analysis.

Studies show that the improvement of clinical signs of dogs and cats with diarrhoea administered probiotics or synbiotics was comparable to those receiving antimicrobials (Schmitz, 2024). The negative implications of antimicrobials on the intestinal microbiome are long standing; this evidence needs to be taken into consideration when considering prescribing antimicrobials (Dahiya and Nigam, 2023). The administration of antimicrobials in cases with acute diarrhoea needs to be performed on a case by case basis by the prescribing clinician.

Historically, veterinary professionals used to recommend “bland diets” for several different reasons, with many of these being disproved or superseded. Recommendations are now for the use of commercial diets designed for gastrointestinal issues. No papers investigating the direct comparison of “bland” homemade diets and commercial gastrointestinal foods for the efficacy of self-limiting acute-onset gastrointestinal issues were found in a literature search.

The author’s team recommends a commercial diet over a home-prepared meal for many reasons, though. As we should be practising evidence-based nutrition, researching the evidence that exists to support a recommendation of gastrointestinal diets rather than “bland” foods can be split into:

- Evidence on home-prepared diets.

- Evidence on highly digestible nutrients.

- Evidence of prebiotics for gastrointestinal issues.

Home-prepared diets

Many arguments are made around the positives and negatives of preparing food at home. What might be deemed as a negative to one person could be viewed as a positive to another; for example, the inconvenience of preparing the food would be seen as a negative to some, while to others it might be seen as an emotionally driven positive to have to cook for a loved one. From a clinical aspect, removing the emotional aspects, home-prepared foods can be unbalanced, open to interpretations (recipe drift), and financially more expensive than commercial diets (Heinze et al, 2012).

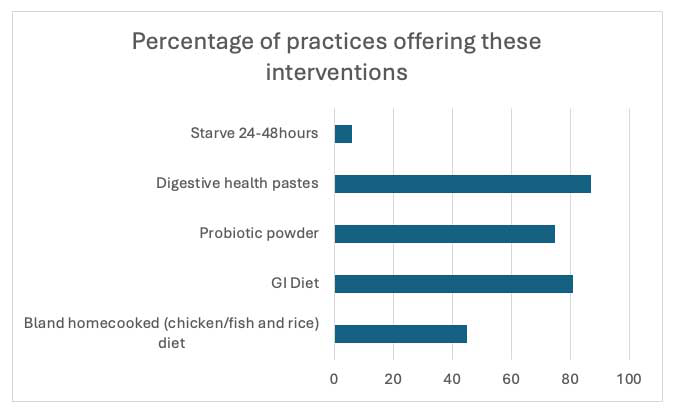

WSAVA guidelines state that a board-certified veterinary nutritionist should create or develop any recipes for them to be complete and balanced (WSAVA, 2021). Would you recommend an unbalanced and incomplete diet to feed their pet? The majority of veterinary professionals would, hopefully, say no. However, in a survey, 45% of veterinary practices recommended feeding a home-prepared, “bland”, chicken/fish-based diet, with no recipe advice given (Figure 2).

Highly digestible diets

In cases of acute diarrhoea, the author’s team recommends highly digestible foods. One of the reasons for this is to reduce the stool volume from the use of low-residue diets. Highly digestible foods will also ensure that the digestive system is receiving the nutrients that it requires from the food that it is being delivered, while potentially in an inflamed or dysbiotic state.

Balance is key, as some carbohydrates (complex fibres) that can decrease the overall digestibility are vital in the diet to act as prebiotics for the gastrointestinal microbiome – you just need the right ones.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are nutrients that support the gastrointestinal biome, whether this is from a nutritional aspect or to help ensure that the environmental conditions within the digestive tract are optimal to support the gastrointestinal biome. Commercial gastrointestinal diets are often supplemented to help maintain this balance.

Evidence indicates a positive effect for acute gastrointestinal disturbances and the role of prebiotics, including mannanoligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides (Xia et al, 2024). These can be obtained from some ingredients, but are unlikely to be present in sufficient quantities in home-prepared diets.

Conclusion

The volume of evidence discussing the negatives and positives of specific nutrients and the role of prebiotics and probiotics is vast. Multiple knowledge summaries and meta-analyses investigating management elements for gastrointestinal issues exist.

All veterinary professionals need to be able to access this information; veterinary surgeons and nurses cannot be the gatekeepers of this knowledge if, in the majority of veterinary practices, it is not them advising clients.

- This article appeared in VN Times (2025), Volume 25, Issue 09/10, Pages 14-15

- Gastrointestinal issues in dogs: updates on the latest research – a Vet Times article from earlier in 2025.

Author

Nicola Lakeman works as the nutrition manager for IVC Evidensia. Nicola graduated from Hartpury College with an honours degree in equine science and subsequently qualified as a veterinary nurse in 2002. Nicola has written for many veterinary publications and textbooks, and is the editor of Aspinall’s Complete Textbook of Veterinary Nursing. Nicola is one of the consultant editors for The Veterinary Nurse. She has won the BVNA/Blue Cross award for animal welfare, the SQP Veterinary Nurse of the Year, the SQP Nutritional Advisor of the Year and, in 2024, the BSAVA Bruce Vivash Jones Award, which is presented annually by the BSAVA as the primary recognition for outstanding contributions to the advancement of small animal veterinary nursing. Nicola has recently gained her Master’s degree in advanced veterinary nursing from the University of Glasgow.

References

- Armstrong PJ (2013). GI intervention: approach to diagnosis and therapy of the patient with acute diarrhea, Today's Vet Pract 2023(May/June): 20-24, 54–56.

- Bell JA et al (2008). Ecological characterization of the colonic microbiota of normal and diarrheic dogs, Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2008: 149694.

- Dahiya D and Nigam PS (2023). Antibiotic-therapy-induced gut dysbiosis affecting gut microbiota-brain axis and cognition: restoration by intake of probiotics and synbiotics, Int J Mol Sci 24(4): 3,074.

- Garcia-Mazcorro JF et al (2017). Molecular assessment of the fecal microbiota in healthy cats and dogs before and during supplementation with fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) and inulin using high-throughput 454-pyrosequencing, Peer J 5: e3184.

- Heinze CR et al (2012). Assessment of commercial diets and recipes for home-prepared diets recommended for dogs with cancer, J Am Vet Med Assoc 241(11): 1,453-1,460.

- Herstad HK et al (2010). Effects of a probiotic intervention in acute canine gastroenteritis – a controlled clinical trial, J Small Anim Pract 51(1): 34-38.

- Jugan MC et al (2017). Use of probiotics in small animal veterinary medicine, J Am Vet Med Assoc 250(5): 519-528.

- O’Neill DG et al (2025). Epidemiology and clinical management of acute diarrhoea in dogs under primary veterinary care in the UK, Plos One 20(6): e0324203.

- Rogers-Smith E (2021). The use of metronidazole in adult dogs with acute onset, uncomplicated, diarrhoea, Vet Evidence 6(4).

- Schmitz SS (2024). Evidence-based use of biotics in the management of gastrointestinal disorders in dogs and cats, Vet Rec 195(S2): 26-32.

- Shmalberg J et al (2019). A randomized double blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial of a probiotic or metronidazole for acute canine diarrhea, Front Vet Sci 6: 163.

- Tong JOP (2019). In canine acute diarrhoea with no identifiable cause, does daily oral probiotic improve the clinical outcomes? Vet Evidence 4(4).

- WSAVA (2021). WSAVA Global Nutrition Committee: guidelines on selecting pet foods, tinyurl.com/4m56y73f

- Xia J et al (2024). The function of probiotics and prebiotics on canine intestinal health and their evaluation criteria, Microorganisms 12(6): 1,248.