6 Jan 2026

Imaging: practical uses within ultrasound, radiography and beyond

Deborah James RVN encourages RVNs to expand their skills and know-how in the area of imaging

Image: motortion / Adobe Stock

The veterinary profession is ever growing, as is the list of postnominals that can be accrued post-qualification.

Diagnostics are no exception to this growth, with more first opinion practices being able to offer further imaging investigations in house without the need for referrals, and referrals are constantly growing their equipment and specialists in house, too. But how do veterinary nurses fit into this growing diagnostic world?

Involvement

According to the RCVS Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses, RVNs and, by extension, SVNs may carry out certain procedures under a vet’s direction and supervision, provided these do not involve entering a body cavity.

Fortunately, radiography, ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scanning fall outside this restriction. The only exception is when image-guided sampling – such as biopsies or needle aspirates – is needed, as these must be performed by a veterinary surgeon (RCVS, 2025).

This being said, legally, RVNs and SVNs are unable to make diagnoses based on the clinical findings, and so the veterinary surgeon is still required to review images and discuss the findings with the owner. Involving veterinary nurses in these procedures offers a practical benefit by giving veterinary surgeons more time to focus on duties that only they can perform – especially as imaging can take considerable time.

It also helps ensure that nurses’ skills are fully used and further developed, which can enhance morale within the team.

In turn, this can lead to better job satisfaction, improved staff retention, and continued growth of the veterinary nursing profession (Sieraj, 2025).

The skills developed through undertaking these procedures allow VNs to engage more actively in clinical discussions and contribute to decision making about a patient’s care and overall treatment pathway. This increased involvement helps to build nurses’ confidence and strengthens collaboration between veterinary surgeons and the nursing team. (Sieraj, 2025).

RVNs are well placed to maintain the high safety standards required under radiation protection legislation (GOV.UK, 2017), with many being radiation protection supervisors, consistently applying monitoring procedures, personal dosimetry and controlled area protocols to minimise any exposure to staff and patients, alike. Integrating veterinary nurse leadership into radiography, ultrasonography and beyond aligns with contemporary models of veterinary team utilisation where tasks are delegated according to competency rather than professional title (Prendergast, 2024).

Radiography

X-rays or radiographs are the most common piece of diagnostic equipment available in first opinion practice. X-rays are produced when electrons hit metal while travelling at high speed. This is achieved by an electric current being conducted through a cathode via a high voltage power source, which enables energy to be released into the x-ray tube, become attracted to the anode and when the energy particles strike the anode in the x-ray head, x-rays are produced (Palgrave, 2022).

As a part of every veterinary nurse’s training journey, they must complete a diagnostic imaging module that includes tasks such as setting up x-rays, positioning patients for x-rays and processing x-rays. With this training and the anaesthetic training taken into consideration, no reason exists why nurses are not able to lead x-ray cases when these come into practice, with the veterinary surgeon using these images to diagnose and create a treatment plan.

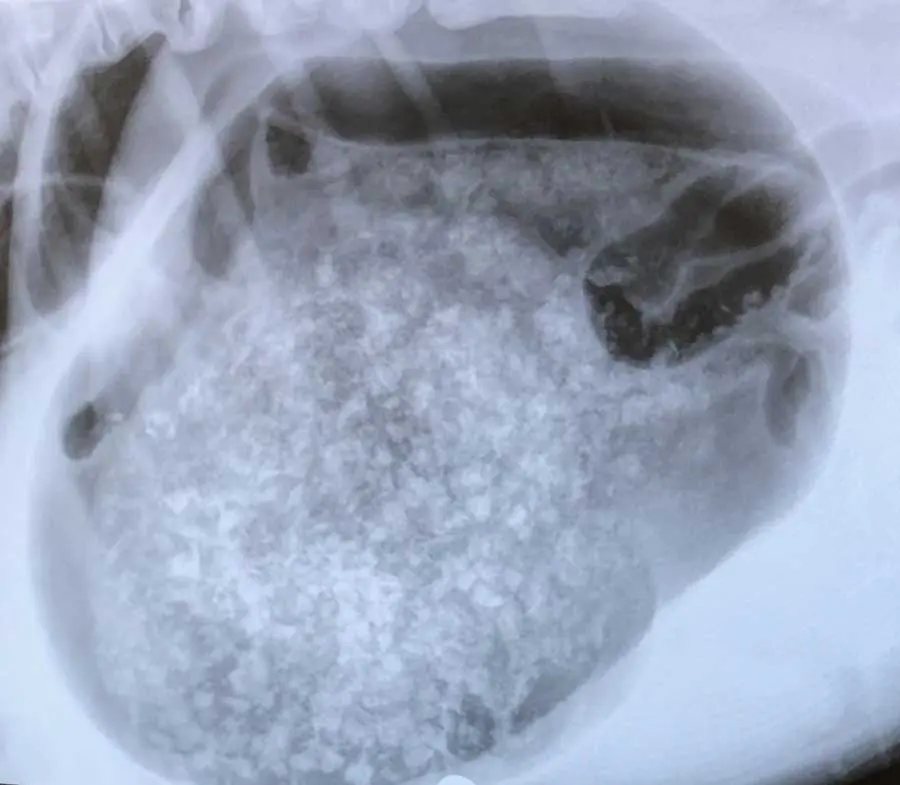

Radiographs can identify injuries or disease processes within the body by visualising bones, organs and other soft tissue structures – anything from fractures and osteosarcomas to bladder stones, foreign bodies and gastric dilation volvulus.

In more recent years, dental radiography has become a more common sight in first opinion practices, with the aim to identify tooth structures below the gingival margin, within the bone – pathology that remains undetected otherwise (Milella, 2022) – with recent studies showing that 27.8% of findings in dogs and 41.7% of findings in cats would be missed (Van Velzen, 2024).

With veterinary nurses already being able to perform thorough oral examinations, scale and polishes, record findings on dental charts and offer home care instructions, no reason exists why they cannot get involved with dental x-rays and be the ones taking the intra-oral dental radiographs. Although challenging at first, dental radiography is changing the landscape of first opinion dentals.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound can be daunting – a screen of black and white blobs with occasional splashes of colour. After being involved in a few of them, RVNs can start registering what a bladder or a kidney looks like.

Firstly, a brief recap on ultrasound. Ultrasonography relies on the way soft tissues absorb and reflect sound waves at different frequencies, the transducer emits these sound waves into the body, where they bounce off internal structures and return to the probe; these returning echoes are then processed and converted into a digital image (Manzi, 2024).

Focused assessment using sonography for trauma (FAST) is a great way for RVNs to be utilised and be used as a part of triage evaluations on patients (Fletcher, 2017).

FAST scans are used to identify free fluid in the abdomen and thorax, and are normally known as A-FAST scans and T-FAST scans. They are non-invasive, quick and can be performed while a physical examination is being carried out, an intravenous catheter being placed or another stabilisation procedure is being started (Benasutti, 2021). They are repeatable and useful when monitoring fluid accumulation in hospitalised patients (Hamel and Berry, 2018).

By getting involved with ultrasound scans, asking questions and getting comfortable with both the machine and organ identification, even just the bladder, is a fantastic step in expanding RVNs’ confidence in practice.

CT scanning

In the past 10 years, CT has become more readily available, with an increase in first opinion practices acquiring them. Similar to radiography, CT uses ionising x-ray radiation, but instead of creating a 2D image, CT spins in a helical motion with several detectors to create a 3D image that can show individual structures in the body in detail, without any overlap (Sieraj, 2025).

CT scanning is complicated, with a multitude of variables, settings and considerations to be aware of in comparison to radiography. Exposures tend to be higher and, as a result, thoracic CT delivers around 70× more radiation than a thoracic x-ray (Harvard Health Publishing, 2021).

With it already being long established that RVNs can take x-ray images, no reason exists why RVNs cannot acquire CT images providing they have had the correct training and competent to do so. The majority of CT scans are used to specifically assess soft tissue and require a contrast, but this is a clinical decision on a case-by-case basis, as side effects such as acute kidney injury and anaphylaxis can occur (Sieraj, 2025).

Once the veterinary surgeon has decided to use the contrast, RVNs can safely administer this under their direction, as with any other medication.

RVNs can then obtain autonomy as the “radiographer” during scans by dictating positioning and collimation factors, which is highly rewarding for the nurses involved.

Conclusion

Crucially, while veterinary nurses can competently perform and manage the technical aspects of image acquisition in radiography, ultrasonography and beyond, the interpretation of images and confirmation of a diagnosis remain the responsibility of the veterinary surgeon.

This division of roles ensures that patient care is both safe and efficient, maximising the strengths of each team member while maintaining compliance with professional regulations.

As imaging demand continues to grow in clinical practice, supporting RVNs in leading radiography procedures represents a progressive and beneficial approach for patients, practitioners, and the wider profession.

Developing confidence and proficiency with imaging modalities requires considerable training, offering RVNs a highly constructive way to apply their advanced skills. This not only enhances job satisfaction but can also have a positive impact on overall team morale. A growing range of imaging-focused webinars and courses designed specifically for RVNs is becoming available, and an increasing number of practices are encouraging their nurses to expand their skills in this area.

With this in mind, there is no time like to present to get involved.

- This article appeared in VN Times (2026), Volume 26, Issue 01/02, Pages 8-12

References

- Benasutti E (2021). Use of FAST Ultrasonography in veterinary emergency rooms, Today’s Veterinary Nurse, tinyurl.com/32k8s3xv

- Fletcher S (2017). FAST scans: What do RVNs need to know?, Veterinary Nursing Journal 32(6): 161-164.

- GOV.UK (2017). The Ionising Radiations Regulations 2017, tinyurl.com/muyzpkba

- Hamel PE and Berry CR (2018). Sonography assessment: overview of AFAST and TFAST, Today’s Veterinary Practice, tinyurl.com/yc6jhctb

- Harvard Health Publishing (2021). Radiation risk from medical imaging, Harvard Health, tinyurl.com/36phm7z9

- Manzi T (2024). Ultrasonography in animals – clinical pathology and procedures, MSD Veterinary Manual, tinyurl.com/4ct5c2eh

- Milella L (2022). Dental radiography, BVNA, tinyurl.com/mtnxr62j

- Palgrave K (2022). Radiography in veterinary practice – a review and update, BVNA, tinyurl.com/bdczbkcx

- Prendergast H (2024). Optimal veterinary team utilization leads to team retention, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 54(2): 317-335.

- RCVS (2025). Code of Professional Conduct for Veterinary Nurses - Professionals, RCVS, tinyurl.com/55ubf6rh

- Sieraj I (2025). Imaging modalities: nurse’s role and conduct in ultrasound and CT, Vet Times, tinyurl.com/3566ubkh

- Van Velzen H (2024). Dental radiography made easy, Vet Times, tinyurl.com/2wnr77zh