2 Sept 2025

Managing dry eye disease in dogs

This article was reproduced based on a guideline written collaboratively with Dômes Pharma by: Rachael Grundon, Bsc, VetMB, CertVR, CertVOphthal, MANZCVS (Surgery), FANZCVS (Ophthal), DipECVO, MRCVS; Maria-Christine Fischer, DipECVO, FHEA, MRCVS; Jens Fritsche, DipECVO; Alexandre Guyonnet, DipECVO; Fernando Laguna Sanz, DipECVO; and Sophie Amiriantz, MSc, DVM

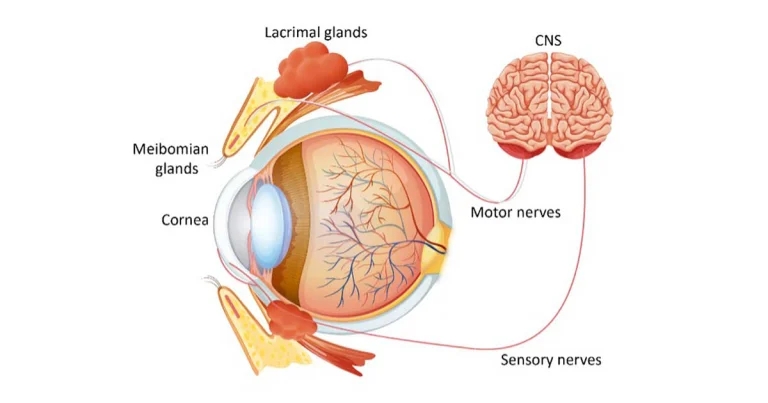

Figure 1. The Tear film unit (note: the goblet cells are not labelled and are found within the conjunctiva). Image: © Dômes Pharma

Dry eye disease (DED, keratoconjunctivitis sicca/KCS) is a disease syndrome of the ocular surface arising from dysfunction of one or more components of the tear film unit (see Figure 1), that is the secretory glands, ocular surface, eyelids and the motor and sensory nerve supply, which create and distribute the preocular tear film. This results in ocular surface inflammation, discomfort and damage, which can be mild to severe.

We tend to place DED into one of three main types:

- Quantitative (reduced aqueous tear production).

- Qualitative (issues with the mucin or lipid layers of the tear film).

- Distributive (issues with the eyelids).

The tear film

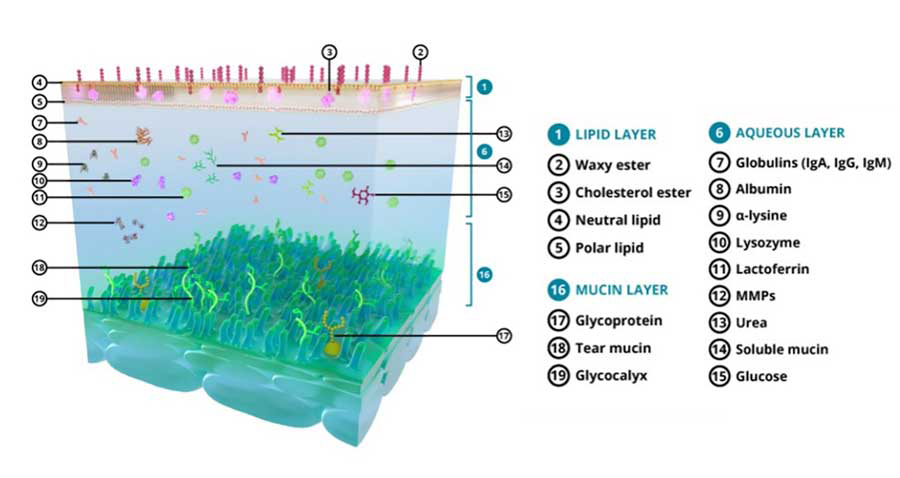

Tears are present over the surface of the eye as a triple-layered film (see Figure 2).

The outer oily or lipid layer is provided by the meibomian glands, located at the edge of the eyelids. It delays tear evaporation and evens out the surface of the tear film.

The middle layer is the aqueous layer, which is secreted by the lacrimal glands including the gland of the third eyelid. It is the thickest layer of the tear film, and provides nutrients, oxygen and microbial protection to the ocular surface. It is also responsible for hydration of, and the smooth movement of, the eyelids over the cornea.

The third, innermost layer is the mucin layer, which is produced largely by the conjunctival goblet cells. The mucins it contains are responsible for the adhesion of the tear film to the ocular surfaces.

Tears are continuously spread over the surface of the eye in a uniform, thin layer by the constant action of the eyelids (and nictitans) during blinking and removed via the nasolacrimal system.

The precorneal tear film serves several functions, including:

- Contribution and maintenance of the refractive, optical surface of the cornea.

- Lubrication between the lids and ocular surface.

- Removal of foreign material and debris from the cornea and conjunctival sac.

- Passage of oxygen and provision of other nutritional requirements to the cornea.

- Protection against microbial insults.

Pathophysiology, aetiology and prevalence of dry eye disease

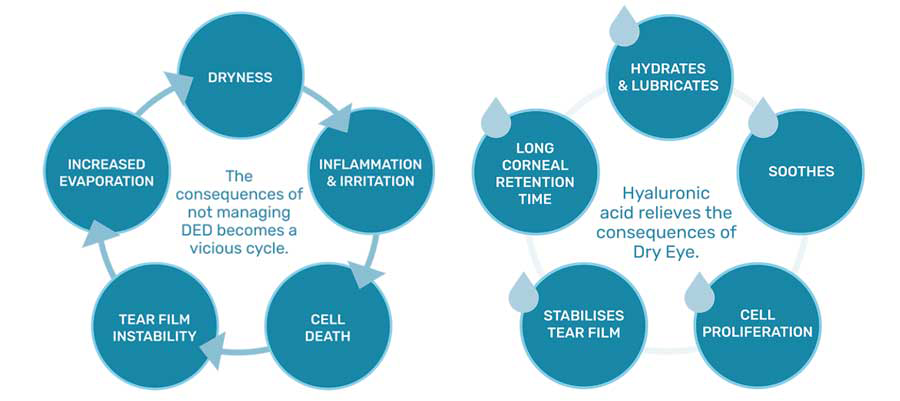

Abnormalities in either the quantity or quality of any tear component (lipid, aqueous, mucus) compromises these tear functions.

Hypertonicity and dehydration of conjunctival and corneal epithelia are initial pathophysiologic events, lack of appropriate lubrication results in frictional irritation of the ocular surface, toxic tissue metabolites may accumulate on the ocular surface and microorganisms more readily colonise affected eyes – all resulting in an increased incidence of ocular surface infections and pathology.

Various aetiologies have been described in dogs and the DAMNIT list can be used systematically to investigate the causes of reduced tear production:

- Developmental: glandular aplasia or hypoplasia.

- Autoimmune adenitis of glandular tissue: the majority of cases of canine DED probably fall into this category. Histopathologic examination of the lacrimal gland reveals break-up of glandular structure with duct dilatation and epithelial cell loss, mononuclear cell infiltration and fibrosis.

- Metabolic: diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, Cushing’s disease.

- Neoplastic: adenoma or adenocarcinoma of the lacrimal gland.

- Neurologic: loss of parasympathetic innervation to lacrimal glands, loss of sensory innervation to the ocular surface.

- Infectious: distemper virus and feline herpesvirus can cause a dacryoadenitis with resultant destruction of the glandular tissue.

- Iatrogenic: surgical gland removal, general anaesthesia and sedation.

- Traumatic: damage to the gland or nerve supply.

- Toxic: sulpha drugs, atropine, topical drugs/preservatives.

One should note that the DAMNIT list does not rank causes in order of severity or frequency.

The dysfunctional factors can be compounded by environmental conditions (such as pollens, wind) and trigger clinical signs in animals that were compensating until then.

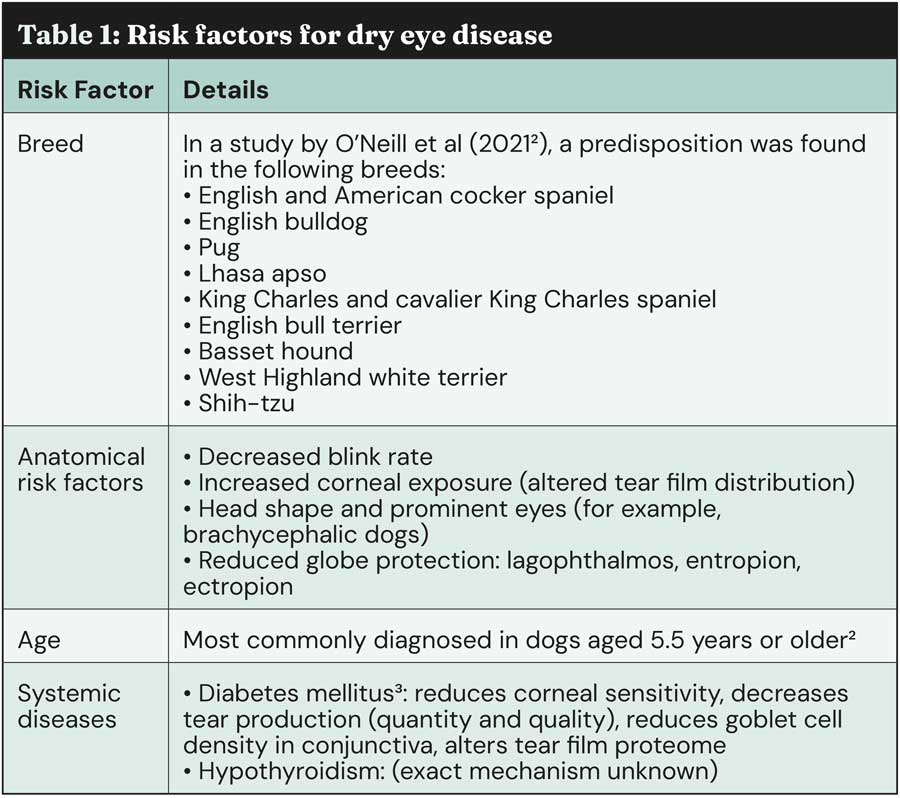

It is suggested that 1 in 22 dogs suffer with dry eye1, however, the true prevalence of DED is hard to ascertain because of under-diagnosing. However, some risk factors (See Table 1) have been clearly identified and should be seen by GP vets as red flags prompting them to further investigate the possibility of DED.

Clinical signs

The presence of even just one of these signs should trigger dry eye investigation:

- Mucoid/mucopurulent discharge (see Figure 3): with aqueous tear film deficiency, you will typically see thick tenacious discharge adhering to corneal ocular surface. The underlying causes are likely over-production of mucins to compensate for aqueous deficiency. Mucopurulent discharge might be misleading and raise suspicion for bacterial infection. Because white blood cells may be present as a result of the inflammation, the presence of mucopurulent discharge does not necessarily indicate secondary bacterial infection.

- Conjunctivitis: dry eyes appear red and inflamed and present with repeated bouts of conjunctivitis that recur when topical medication is discontinued.

- Keratitis (see Figure 4): corneal vascularisation and pigmentation are common and can lead to loss of vision. The cornea appears lacklustre and sometimes cloudy. These secondary changes are relatively non-specific and reflect the chronic nature of the disease.

- Corneal ulcers: corneal ulceration can occur in severe or acute cases, and recurring ulcers should raise suspicion. Due to the lack of tear production, the healing of corneal ulceration is severely impaired.

- Blepharitis: swollen eyelid margins and periocular dermatitis can occur secondary to accumulation of periocular discharge. Inspissated meibomian glands and multiple chalazia occur with meibomianitis, which is associated with qualitative tear film deficiency.

- Ocular discomfort: people with dry eye report a foreign body sensation and stinging. Dogs present with variably severe blepharospasm and third eyelid protrusion, most likely related to frictional irritation. Because dogs rarely rub their eyes when irritated, ocular discomfort can be difficult to detect, and will be more obvious in the more acute cases.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the history, the presence of compatible clinical signs and supported by diagnostic tests.

A full physical examination and further investigation should be taken into consideration to rule out systemic underlying causes such as metabolic diseases.

A complete ophthalmic examination is necessary to assess vision, clinical signs of dry eye disease and neurological abnormalities. In addition, assessment of the nares for dryness is essential in diagnosing neurogenic dry eye.

The Schirmer tear test (STT) remains the standard means for quantifying aqueous tear production and diagnosing quantitative tear film deficiency. The STT should be performed on every patient with an eye complaint (unless a deep ulcer is present, in which case avoid or take great care). It should be performed first in the ophthalmic exam to avoid falsely high values from reflex tearing associated with examination of the eye, and prior to application of any topical agents.

Without touching the bent end, the STT strip is inserted into the lateral half of the lower conjunctival fornix. The strip remains in place for one minute and the readings are taken immediately after removal.

Values between 10-15 mm/min can be consistent with aqueous tear deficiency if compatible with clinical signs, values between 5-10 mm/min are highly suspicious and values of less than 5mm/min are characteristic of severe disease. In case of doubt a re-examination should be scheduled for repeat measurement4.

Stains such as fluorescein can be used to assess the integrity of the epithelium and stability of the precorneal tear film. Tear Film Break Up Time (TFBUT) (see Figure 5) can be used to evaluate the quality and stability of the tear film and may be abnormal in the presence of a normal STT result. Lissamine green and Rose Bengal stains can further aid the diagnosis but are more commonly used in referral practice.

Assessment of the blink rate and effectiveness is especially helpful in brachycephalic dogs. In case of incomplete and infrequent blinking one must assume greater evaporative loss. Taking slow-motion videos can help identify incomplete eyelid closure.

Management

When confronted with dry eye patients, the practitioner should remember to treat the patient as a whole, and not just the STT value.

Ocular pain, comfort and complications are as critical as tear production, if not more. Additionally, the owner will be more mindful of clinical signs than of diagnostic test results.

Recommendations for initial management include:

- Lacrimostimulants/immune-modulating agents: ciclosporin, a calcineurin inhibitor, remains the cornerstone of immune mediated dry eye treatment as it has both immune-modulating and tear stimulating properties and should be used as a first-line treatment. The recommended regimen is topical application every 12 hours. Ciclosporin typically increases tear production within two to three weeks of therapy, but some dogs may require two to three months of therapy before improvement of STT values are observed and lifelong treatment is usually needed in most dry eye patients. Ciclosporin will, however, only be effective if some functional lacrimal gland remains.

- Lacrimomimetics/tear supplements: lacrimomimetics are warranted in the management of tear film abnormalities as an adjunct to lacrimostimulant therapy. Many tear supplements exist, however a good all-rounder for most patients is hyaluronic acid: a naturally occurring, high molecular weight glycosaminoglycan with excellent viscoelastic, mucinomimetic and lubricating properties and serves as an effective protectant for the ocular surface. The nature of hyaluronic acid – concentration and linear or cross-linked – (see Figure 6) impacts the performance and frequency at which these tear supplements should be administered5.

- Topical hygiene: mucopurulent discharge is commonly observed in cases of KCS. Secondary bacterial infections are frequent in dry eye due to inadequate cleansing of the ocular surface. Various types of ocular cleansers specifically formulated for animals and containing surface active agents (polysorbate), chelators (Tris, EDTA) as well as antiseptic compounds (salicylic acid, sodium borate) are available on the market.

- Antibiotic treatment is usually not indicated as the discharge will most likely improve with control of the underlying disease. Topical broad-spectrum antibiotics are essential if corneal ulceration is present.

Involvement of the owner is essential in the management of DED: teaching them good practices of eye cleaning and treatment administration is essential. Making sure they understand improvement can take several weeks, and treatment is often life-long.

In the absence of response to first line treatment, owner compliance should be evaluated and referring your patient to, or obtaining advice from, a veterinary ophthalmologist is advised.

Summary

Dry eye disease, or keratoconjunctivitis sicca, results from the dysfunction of one or multiple structures of the tear unit, leading to clinical signs (mucopurulent discharge, recurrent conjunctivitis) along with compounding environmental conditions.

DED has many aetiologies, most frequently immune-mediated in dogs. Some risk factors such as breed, age or systemic diseases are red flags the GP should take into consideration.

The diagnostic process involves several steps, including quantification of tear production with a Schirmer tear test alongside assessment of clinical signs. Ciclosporin should be considered first-line treatment alongside tear supplements as an adjunct.

Owner compliance is critical in the success of DED management, and they must be fully aware that this is a chronic disease and that treatment must be continued for life.

To view Dômes Pharma’s Practical Ophthalmology, step-by-step guide, visit the website.

Authors

This article was reproduced based on a guideline written collaboratively with Dômes Pharma by: Rachael Grundon, Bsc, VetMB, CertVR, CertVOphthal, MANZCVS (Surgery), FANZCVS (Ophthal), DipECVO, MRCVS; Maria-Christine Fischer, DipECVO, FHEA, MRCVS; Jens Fritsche, DipECVO; Alexandre Guyonnet, DipECVO; Fernando Laguna Sanz, DipECVO; and Sophie Amiriantz, MSc, DVM

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 35, Pages 14-17

- Corneal ulcer update – case management and new therapies

References

- 1. Pierce V and Williams D (2006). Determination of Schirmer tear test values in 1000 dogs, BSAVA Abstracts, BSAVA, Gloucester.

- 2. O’Neill DG, Brodbelt DC, Keddy A, Church DB and Sanchez RF (2021). Keratoconjunctivitis sicca in dogs under primary veterinary care in the UK: an epidemiological study, Journal of Small Animal Practice 62(8): 636–645.

- 3. Cullen CL, Ihle SL, Webb AA and McCarville C (2005). Keratoconjunctival effects of diabetes mellitus in dogs, Veterinary Ophthalmology 8(4): 215–224.

- 4. Featherstone HJ and Heinrich CL (2021). Ophthalmic examination and diagnostics. In Gelatt KN (ed), Veterinary Ophthalmology (6th edn), Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, IO.

- 5. Grego AL, Fankhauser AD, Behan EK et al (2024). Comparative fluorophotometric evaluation of the ocular surface retention time of cross-linked and linear hyaluronic acid ocular eye drops on healthy dogs, Veterinary Research Communications 48: 4,191–4,199.